Dick Everitt helps illuminate our understanding of lighthouse characteristics on charts, their dipping distances and loom...

Sailors have been using lighthouses as navigation aids for thousands of years. One of the seven wonders of the ancient world, the Pharos of Alexandria, dated from before 200BC and even today, with GPS navigation, it’s quite reassuring to see a light appear on the horizon where you hoped it should be.

Lighthouse characteristics on a chart are given in a set format. Admiralty booklet 5011 covers all the variations, but basically if you see, say, ‘Fl.5s 49m 28M’ it means a white light flashes every 5 seconds, the centre of the light is 49m above MHWS (mean high water springs) and in good visibility, the light is powerful enough to be seen 28 miles away. (As an aide-mémoire, I remember the small ‘m’ is for metres and the big ‘M’ is for the bigger miles).

Don’t expect to see the light at 28 miles from the deck of a small yacht – you’d need to be high up on the bridge of a big ship for that. Our low eye height and the curvature of the earth means the range of the light is restricted to its ‘dipping distance’.

Handy ‘dipping distance’ tables in almanacs, based on the height of the light and our eye height, give a rough guide to the range. Say our eye height is 3m, then our 49m-tall light will dip, or just peep, over the horizon at about 18 miles, so it’s worth writing 18M in pencil on the chart and drawing an arc at that range with a pair of compasses.

Smudged halo effect

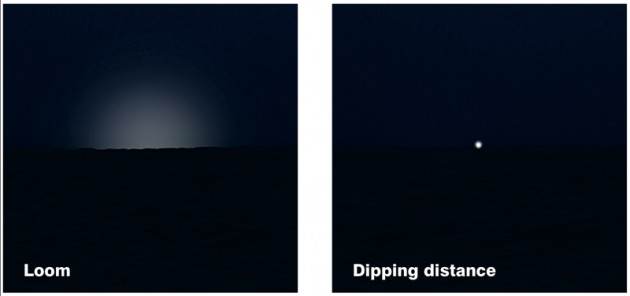

Don’t confuse the light ‘dipping’ on the horizon with its ‘loom’. On a good night the light is refracted through the atmosphere and creates a smudged halo effect at a much greater distance.

To get the ‘dipping distance’ we need a pinpoint of light to just appear over the horizon. Large waves will make it ‘dip’ more often but on a calm sea you can move your eye level up and down to make the light ‘dip’. This gives us a rough distance off.

Now we need to check it’s the right light. You can time the flash with a stopwatch, or just count ‘Mississippi one’, ‘Mississippi two’, etc, but always time the light before you check its characteristics on the chart, because it’s very easy to ‘see what you want to see’ and adjust your timings to suit.

It’s uncanny how the lights of cars passing a gap in the trees will give the correct timing of the light that you want to be there – especially if you’re cold, tired and a bit seasick!

Some lighthouses have coloured sector lights that shine over danger areas, so to stay in the channel you’d need to see a white light ahead: if you stray to port the light would show red, and if you stray to starboard the light would show green. High-intensity lights are also used to lead you in and are so bright that they can clearly be seen in daylight.

Lights in daylight

What do lighthouses look like in daylight? This is a favourite question of a Yachtmaster examiner I know, because the chart doesn’t tell you. What’s needed is a pilot book, or sometimes a ‘list of lights’ in an almanac, to give a description of the structure.

For instance, the short Anvil Point lighthouse and the tall Portland Bill light are described on the chart as roughly the same height, because it’s their light height above MHWS – but some students expect to see a tall tower at Anvil Point, not a short tower on a high cliff.

Related articles

- Nav in a Nutshell: Clearing bearings

- Nav in a Nutshell: Using transits

- Nav in a Nutshell: Navigate by ‘feel’ using an echo sounder

Port authority lights that guide you into tricky harbour entrances are still very useful, but sadly some General Lighthouse Authority (GLA) ones and their attendant foghorns seem to be under constant financial scrutiny, as most shipping nowadays navigates by GPS. The GLA is keeping up with the times by experimenting with AIS (automatic identification system) so some of its lighthouses appear on certain AIS chart and radar overlay systems, but not everyone has AIS, and small-boat skippers find lighthouses useful and reassuring.

And if they’re honest, many big ship skippers appreciate a physical confirmation of their electronic navigation when they see a light looming out of the murk after a long ocean passage.