We took the PBO Project Boat on a shakedown sail - across the Channel and back! Read on to find out how Hantu Biru got on...

You should never sail to a deadline, they say. But sometimes, you can’t escape the fact that life often pushes sailing into second place. We had set Hantu Biru’s launch date for a Monday in late August and booked the crane weeks in advance, with the vague thought that maybe we’d head cross-Channel later that week to round off the restoration with some real sailing.

You can’t turn down a weather window like this – especially when the next day was blowing a gale from the south-west!

We checked the weather as she was lowered into the water at Cobb’s Quay Marina. That evening, there was a weather window of 12 hours of westerly winds, giving way to a very windy and wet patch of low pressure, followed by a steady south-westerly. On the one hand, for a quick trip across the Channel and back you just can’t turn down a weather window like that, which gives you the opportunity of not beating across the Channel. But on the other hand, the boat was only going in the water that morning after nine months ashore, with an untried inboard engine, and we were tired from a marathon session to get the boat rigged and ready for launch. However, we resolved to get the boat in the water and see how things panned out.

We spent the morning giving the engine a good test, running it for two hours non-stop, and the boat’s handling exceeded our expectations. Best of all, the engine revved fully, idled easily and was quite happy in its new installation, with no leaks, drips or excess vibration. That was one hurdle cleared.

A check of the midday forecast showed that our window would remain open for long enough to get across the Channel. That settled it: sailing across the Channel in a small boat is one thing, but beating all the way across? No way! Work deadlines meant that if we were going to go, now was the time.

A manic few hours followed, where we called at the chandlery for charts, flares and supplies, at the supermarket for victuals and at the fuel barge to top up Hantu Biru’s new diesel tank. Finally,

we loaded a liferaft and our kit onto the boat and cast off from our temporary mooring at Cobb’s Quay. Motoring through the bridges at their 1530 opening, we hoisted the sails once out into Poole Harbour and made our way to the mouth of the harbour.

Considerations

A small boat is not very visible to shipping, and the Channel is one of the most congested shipping lanes in the world. We didn’t have AIS, but a hand bearing compass and regular scans of the horizon kept us aware of ship movements.

Passage planning on Hantu Biru: on a boat of her size and pedigree, 4 knots is a safe speed at which to plan a passage

When to leave: Tides at the Cherbourg end aren’t too critical as the flow in and out of the harbour is minimal. But on the way back to Poole or the Solent, it makes sense if possible to time your arrival so that a flood tide can take you in. Lights: A night passage is nothing too extreme, but you’ll need to make sure your lights are working and that you have everything needed (hand bearing compass, food, drink, warm clothes) to hand to make it as simple as possible.

Safety kit: It’s a fact of life that you need the same kit on a big boat as well as a small boat – there’s just less space for it on the small boat! We had a four-man liferaft, and added a lifebuoy light to our horseshoe lifebuoy. Lifejackets and harness lines are also essential for night sailing. A radar reflector should help ships to spot you, and a powerful torch is also useful.

The trip across

Hantu Biru tramped along nicely under full sail in the flat water of the lee of Old Harry and Swanage. But as she stretched her legs and we headed further south, the sea state began to worsen. A weather-going tide and a brisk 15+ knots of wind meant that life was fairly uncomfortable for a while, especially as we passed over the tail end of Peveril Ledge, where green water cascaded over the deck and Hantu Biru leapt into troughs with the consistency of concrete.

A quick (if wet) two reefs in the main and a few rolls in the jib later, her motion improved considerably and she settled down, heading for Cherbourg with a bone in her teeth.

As dusk began to fall we spotted the first of many ships, a tanker, which passed harmlessly a few miles ahead. On went the tricolour and we served up some hot pasta – no mean feat in a small cabin that was heeled hard and bouncing around like a trampoline.

A lot more comfortable

Night fell, and with it the tide turned. No longer dragging us to windward, the sea state eased a little and so did the wind, making life a lot more comfortable. As Hantu Biru sailed steadily south, the ships, now nothing more than pinpricks of light, began to line up on their way down-Channel. Our tricolour, shining brightly at the masthead, seemed insignificant in the inky blackness, but one by one the ships passed on, their bearings changing, and we were soon alone on the pitch-black sea.

Somewhere mid-Channel, the cloudy skies cleared to reveal the star-studded night sky. Finally, we had something other than a wildly jumping compass card to steer for, and we marvelled at the heavens, the plough and North Star hanging just above our transom.

As the miles on the GPS slowly ticked down, we began to see the lights of ships exiting the Casquets TSS to our west and heading up-Channel for their presumed destinations of Antwerp, Rotterdam and Felixstowe. And then, finally, the French coast was visible – the loom of some land. The visibility was by now so good that we could see the loom of the Cotentin Peninsula, the lights of the power station at Cap de la Hague, and the sweeping lights of the lighthouses at Cap de la Hague to the west and Pointe de Barfleur to the east. Our destination lay somewhere between the two and the tide turned once more, sweeping us back to the east and the granite breakwater of Cherbourg’s Grande Rade.

It was many hours later that we finally got close enough to identify the safewater mark off Cherbourg’s west entrance. As we approached, the hitherto clear sky began to cloud over and the wind to die, but we kept sailing until we were past the imposing breakwater and inside the Grande Rade. Coming onto the wind in flat water we turned the key in Hantu Biru’s new engine. To our relief it fired first cough, puttering away happily as we stowed the sails.

We motored past the zone militaire towards the welcoming Port Chantereyne in the damp twilight. An empty berth on K pontoon beckoned, and we stepped gingerly onto the notoriously springy finger pontoon, tied up and killed the engine, some 14 hours after leaving Poole.

As we wrote up the logbook and fried up some celebratory bacon, the first drops of rain began to fall, and the wind began to whistle through Hantu Biru’s rigging. Our weather window had slammed shut – we had arrived just in time.

Now, I don’t know if it always rains in Cherbourg, but it always seems to be raining when I’m there. The rest of the day saw biblical rain, allowing us to catch up on sleep, head to the local Carrefour for some essential supplies and fix a few minor leaks that the green water sluicing over the deck had revealed. A meal in a cheese-themed restaurant rounded off the day and we retired early.

The trip back

The rain and wind was forecast to clear by dawn, leaving behind a steady 15-knot south-westerly breeze – ideal for a fairly rapid return trip (on paper, at least). And so, at 0530 we stumbled out of our bunks, bleary-eyed, and motored away from the slumbering marina towards the open sea once again.

In the lee of the Cotentin peninsula, the sea was flat, and we slipped along nicely on a broad reach. But the rain gods had neglected to read the forecast and showered us with rain of varying intensity as the sun came up. As it did, the tide turned; and no longer taking us to weather, the apparent wind also died and came aft. This seemed an opportunity too good to refuse, so we hoisted the boat’s new Rolly Tasker spinnaker, which increased our speed to around 5 knots, knocking a few hours off our ETA.

As we cleared the land, the sea state began to increase, as did the wind. By now we were having a great sail. The swell was on the quarter, as was the wind, which combined with the large spinnaker lent Hantu Biru her wings.

With a twitch of the tiller at the top of a wave, Hantu Biru would begin to surf down its front, and we hit speeds of up to 8.1 knots through the water as she picked up her skirts.

We spent a few hours surfing down the waves, avoiding ships and frantically trimming the spinnaker before realising that it had become really quite windy. Looking astern, white horses leapt around our wake, and the wooden spinnaker pole was beginning to flex alarmingly as the boat slowed after a surf. Discretion being the better part of valour, we doused the spinnaker and unrolled the jib, which was more controllable – and not much slower.

Nearing the English coast

The wind began to howl as we approached the English coast, and a misty, dense rain set in, reducing the visibility to under a mile. Usually on a Channel crossing you can see the Isle of Wight’s chalk cliffs and the Purbeck hills from miles out, but on this occasion all we could see was grey sea, grey sky and the occasional grey bird.

Ten miles off, the tide turned as predicted to take us back to windward and back onto our waypoint. This increased the wind and waves again, so we slabbed in a reef to make life more comfortable. Making the tea became a popular chore as the warm, dry cabin beckoned, our Sikaflex leak fixes having done their job well.

Finally, we found the buoys marking the Swash channel and sailed our way along the training bank which marks its western edge, 12 hours after leaving Cherbourg and our warm bunks. This fantastic passage finished off a tremendous few days that had tested Hantu Biru and the repairs and upgrades we’d made in conditions more extreme than we’d yet encountered. Channel crossings in a small, relatively slow boat are still not to be undertaken lightly, but Hantu Biru had shown herself the equal of Channel waves, overfalls and rainstorms, and posted some impressive top speeds under spinnaker. What a trip!

Passage planning

On a boat of Hantu Biru’s size and pedigree, and with a reasonable breeze, 4 knots is a safe speed at which to plan a passage. The forecast westerly wind would put us somewhere between a beam reach and a fetch, which would give us around 4 knots – but were the wind to come aft at all, that would probably increase to 5 knots.

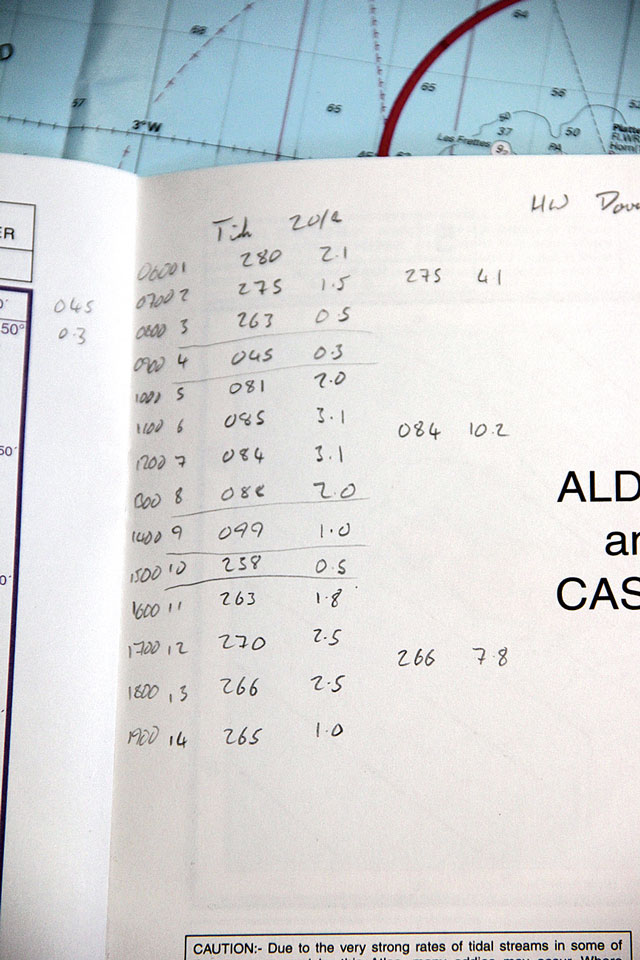

On a relatively slow boat, sailing a direct course through the water is all the more important: you’ll sail much further if you try to make your heading match the bearing to waypoint the whole way across. Here’s a quick refresher from our journey home…

1 Divide the trip into hourly segments for your intended speed through the water, and work out the tidal rate and direction for each hour, using either tidal diamonds or the diagrams in a tide book.

2 Using an average of these, east and west, gives you a number of vectors, which you can

then transfer to the chart at your starting point.

3Draw an arc from the end of these vectors so that it bisects your original pencil line. This is your course to steer.

As it happens, many boats that can maintain a steady 5 knots over this distance (60NM) will have an estimated time of 12 hours – enough for the east- and west-going tides to balance themselves out. Hantu Biru had an estimated 14 hours at sea, which meant that we needed to head 352° magnetic on the way back, slightly to the east of our destination – to counteract the two hours of extra west-going tide that we’d encounter at the end.