Rupert Holmes charts the innovations and developments in yacht design that marked the post-war years through the 1950s

Although the post war period was a time of scarcity – food rationing in the UK continued until 1954 – it was also a period of great optimism.

There was more social mobility than ever before and many of the new technologies that had been developed for the war effort were now available for civilian use.

This optimism meant the prospect of owning a boat was brought to a far wider audience than had ever previously been possible.

This was also a time at which the mainstream media was strongly promoting boating.

The Mirror, Express and Daily Mail, for example, all sponsored boat shows or small boat designs, while the Sunday Times and Observer would later sponsor trans-ocean solo races.

In addition, new materials that had originally been developed for aircraft construction were now available for boat building. These included plywood and fibreglass, as well as techniques such as hot moulded timber.

Hamble-based Fairey Marine, the company that was spun out of Fairey Aviation after the end of the war, pioneered this technique starting with the Uffa Fox-designed 12ft Firefly dinghy in the late 1940s.

Uffa Fox sailing with the Duke of Edinburgh and a young Prince Charles. Credit: Keystone Pictures USA/Alamy

Designer profile: Uffa Fox (1898-1972)

The Cowes, Isle of Wight-based designer and boatbuilder was a prolific innovator and a colourful, larger-than-life character.

He served an apprenticeship at Saunders Roe in East Cowes in which he was involved in the development of hydroplanes.

This was a key influence that led him to develop the first planing dinghy – the International 14 Avenger in 1928.

Uffa was well travelled and incorporated the ideas of others in his work, attempting to improve on their ideas.

During the war he developed the Airborne Lifeboat that could be carried under the fuselage of a Lancaster bomber and dropped near pilots who had been forced to eject from their aircraft over the sea.

After the war he designed a wide variety of successful boats, from popular dinghies to large yachts.

He also had a huge enthusiasm for sharing his knowledge and experience both through writing – he penned more than a dozen books that were valued for their insights into boat design, seamanship and performance – and as a popular broadcaster.

He became a friend of the Duke of Edinburgh, racing with him during Cowes Week in the Flying 15 Cowslip and later in the Dragon Bluebottle, and was instrumental in teaching the then young Prince Charles and Princess Anne to sail.

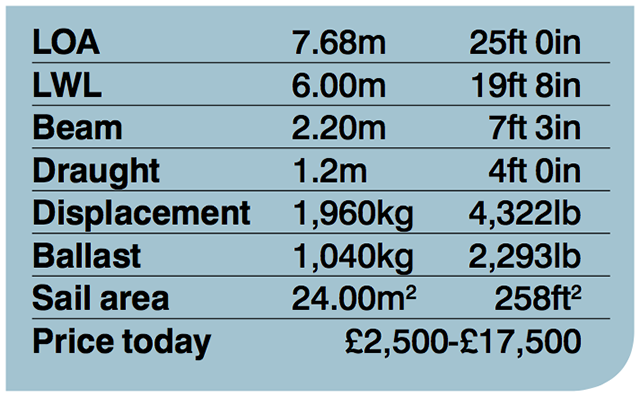

Folkboat

1942

A later fibreglass Folkboat that remains true to the original concept. Credit: Rupert Holmes

Although not a post-war design – it dates from 1942 – Tord Sunden’s 25ft Folkboat was arguably the first vessel intended from the outset as a people’s boat that would bring sailing to a far wider audience than ever before.

Production boomed at yards across Europe after the war, with more than 4,000 built.

The original design was of clinker construction, which is quicker to build than carvel hulls, although many later boats, especially those from yards in the UK and Poland, had carvel hulls.

Most of these also had larger coachroofs that provided more headroom and accommodation volume than the simple and scant interior of the original design.

Although the boat was primarily intended for racing and weekending, a powerful bermudan rig provided excellent performance by the standards of the times, even in light airs.

At the same time the boat proved very capable in strong winds thanks to a beautifully balanced hull shape and mammoth 55% ballast ratio.

Many notable ocean crossings have been undertaken in Folkboats, despite their diminutive size.

On the downside, by today’s standards they are relatively slow and can be very wet, especially to windward.

Construction changed to fibreglass towards the end of the 1960s and the class inspired many well known derivative designs from the early 1960s through to the late 1970s.

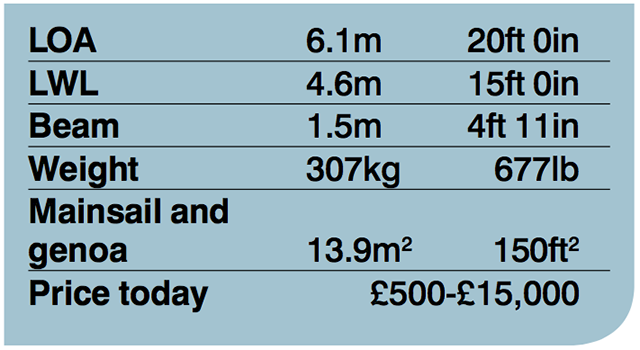

Flying 15

1947

Vamoose, an early Flying 15 still in use. Tim Jeffreys/Cowes Classics

In an era in which planing dinghies were still unusual, this 20ft planing keelboat, designed by Uffa Fox in 1947, stood out among her contemporaries.

The powerful spade rudder mounted well aft gave good control, while the low centre of gravity fin keel minimised weight and wetted surface area.

More than 70 years later it remains a popular racing class with active fleets around the globe and a well attended and hotly contested world championship.

Although most keelboats of this era were heavy displacement long keel designs, the ideas Uffa incorporated into the Flying 15 had already been successfully implemented towards the end of the 19th century.

Cowes-based Charles Sibbeck’s 20ft half-rater Diamond of 1897 and 45ft Bona Fide of 1899, for instance, were both light displacement designs with a short chord bulb keel and separate rudder positioned well aft.

At an even earlier date the prolific American designer Nathaniel Herreshoff had produced Dilemma in a similar vein.

This boat proved to be so fast that similar designs were banned by the rating rules used for racing at the time and were mostly ignored for much of the next

80 years.

This was by no means the only time the racing community has slowed the progression of yacht design – many innovations have been rejected because they threatened the establishment, rather than because they didn’t work.

A boat that totally outclassed existing designs was all too often seen as a threat to the status quo, resulting in a de facto ban.

Even worse, cruising sailors often want boats based on what they perceive to be the latest cutting edge thinking, so the design of raceboats is strongly reflected in the cruising yachts of the same era.

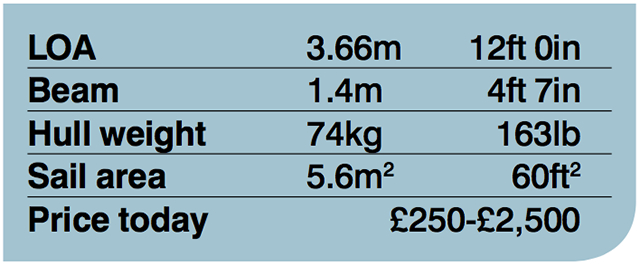

Firefly

1948

Still popular today, the Firefly was the first mass-produced boat. Credit: Richard Wareham Fotografie/Alamy

This was the first sailing boat to be mass produced and was generally built in batches of two or three dozen boats.

Hull construction was of three layers of 1⁄8in (3mm) spruce that had been stockpiled for the war effort, changing to 2.5mm agba veneer when this became unavailable.

The planks were applied over a male mould with each temporarily held in place with staples.

Once planked up the boats were put in a vacuum bag and heated under pressure in an autoclave for 30 minutes.

This process compressed the planks together, activated the glue and helped it impregnate into the timber.

The result was a lightweight yet stiff monocoque structure that could be built in around half the time of a traditionally planked clinker dinghy.

It sold for just £65, including an aluminium mast.

When the boat was selected for the 1948 Olympics, in which legendary Danish sailor Paul Elvström won his first of his four gold medals, the Firefly quickly gained recognition and popularity.

Hot-moulded construction was quickly rolled out to a wider range of craft, including the 15ft Albacore, the 18ft Jollyboat dinghy and the Olympic Flying Dutchman class.

It was also used for larger boats, including the 26ft and 31ft Fairey Atalantas.

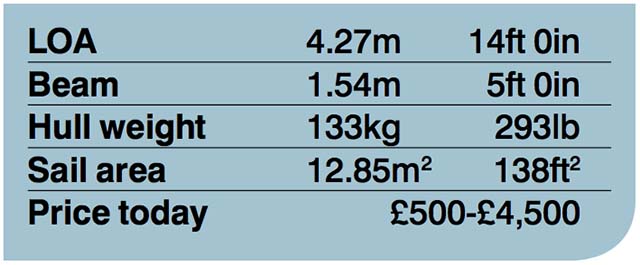

GP14

1949

More than 14,000 GP14s have been built and the class still has an active racing programme. Credit: Andrew Hayes/Alamy

Although plywood has been around since the mid 1800s, and the ubiquitous 8ft x 4ft sheets since the late 1920s, it was not until the mid 1930s that a waterproof glue that enabled the material to be used in boat building was developed.

Production mushroomed during the war, with engineering grade plywoods used for aircraft production, among other things.

This material opened up many new possibilities for boatbuilding, speeding up production, which reduced labour costs and allowed for easier home building than a traditional planked hull.

One of the first post-war boats designed specifically to be built of plywood was Jack Holt’s GP14 dinghy.

The idea was for a cost-effective multi-purpose family boat that could be kept at home and trailed to a variety of launching sites behind a modest car.

It quickly proved popular and more than 14,000 have been built.

Holt went on to design some 40 different dinghy classes, including the 11ft gunter rigged Heron in 1950.

This was intended to be a boat just big enough for a family that could be carried on the roof of a small car.

While many of the earliest plywood dinghies sported a very distinctive hard chine shape, Holt’s 1955 Enterprise dinghy had a double chine, more closely mimicking the shape of a round bilge hull.

Plywood dinghies from a variety of designers quickly came to form the backbone of the fleets sailed at many of the new sailing clubs around the country that sprang up in the 1950s and 1960s.

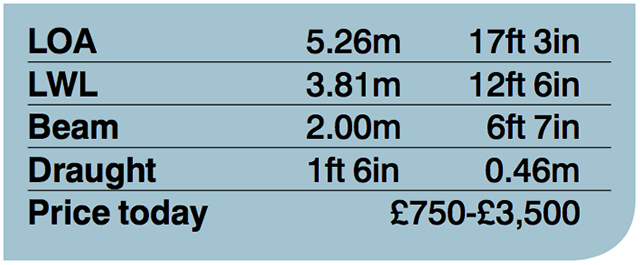

Silhouette

1953

The Silhouette satis ed the demand for self-build boats in the 1950s. This example is a breglass MK3 model. Credit: David Harding/Sailing Scenes

There was pent-up demand for affordable cruising boats in the post war period, and the 17ft Robert Tucker designed Silhouette proved hugely successful in satisfying this demand – by the early 1960s there were already more than 1,000 afloat and some 3,000 were built before production of the Mk lV and V finished in the mid 1970s.

Tucker designed the boat for home building in plywood, with material costs estimated at just £100.

Most early boats were built by their owners from scratch, although production building started in 1956, with the boats priced at £245 and the fibreglass Mklll version was introduced in 1965.

Early boats had a cramped two berth cabin, plus room for two children under a boom tent in the cockpit, while later boats made better use of the limited cabin space.

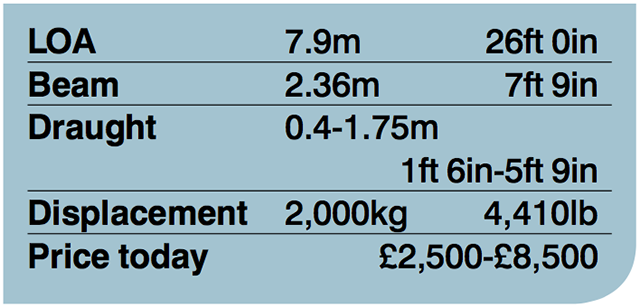

Fairey Atalanta 26

1955

Curved styling of the Fairey Atalanta is influenced by its hot moulded ply construction. Credit Alan Kelly/Atalanta Owners Association

Despite its unconventional styling, the 26ft Fairey Atalanta was a masterpiece of design and engineering by Uffa Fox.

It was built using the same hot moulded process as the Firefly, but using twice as many veneers of timber.

The unusual curved styling was partly a function of the construction method, but also served to create an inherently stiff, strong and lightweight structure.

The boat has shallow draught with twin swing keels, each weighing 215kg, plus the then luxury of an inboard engine, six berths and headroom of close to 6ft.

It could be trailer sailed, yet several have crossed the Atlantic, including one in the gruelling OSTAR race, and another has completed a circumnavigation.

This was the first of a number of similar designs from 20-31ft, including the 25ft Fairey Fisherman, which was based on a lifeboat hull.

Fairey Marine also produced a range of fast and sporty motor cruisers that were well regarded in their day and are now sought-after classics.

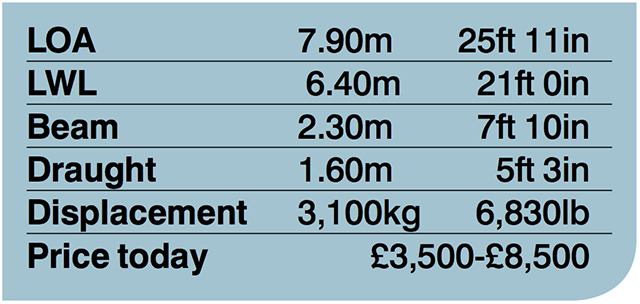

SCOD

1955

SCOD employed traditional carvel construction. credit: David Harding/sailingscenes

The boating world is often one that’s slow to change and by no means all popular designs of the 1950s used the new materials.

Larger yachts and those from more established designers and boat builders still tended to be hand built using the same tried and tested techniques as they had been for the previous 100 years or more.

However, top-quality timber such as teak, oak and pitch pine were no longer available, or were so expensive that they could only be used on the highest budget projects.

Instead less durable timber such as mahogany, iroko and larch was generally used, with oak reserved mostly for structural frames.

Traditional carvel construction was employed for the South Coast One Design, a 26ft Charles A Nicholson-designed long keel cruiser/racer.

Although only 12in longer than the Folkboat, this was a very different craft, both heavier and more powerful, with a deep 5ft 3in draught and more freeboard.

There is therefore a lot more interior space, with full headroom, four berths, a workable galley, separate forecabin and separate heads.

Although SCODs were significantly more expensive than a Folkboat, yet alone a plywood design of similar size, more than 100 were built by various yards on the south coast over a 15-year period.

Early catamarans

1953-56

The Shearwater catamaran was unlike any other boat when rst launched in 1956. The class still has an active following – this was the 2013 national championship. Credit: Rupert Holmes

There was nothing new about the concept of catamarans in the 1950s – Polynesians started voyaging in them thousands of years earlier.

Somewhat more recently, Herreshoff had experimented successfully with catamaran designs as early as the 1870s, while a commodore of the New York Yacht Club in the same era imported a traditional catamaran from Polynesia.

However it was not until the 1950s that the modern multihull revolution finally got under way.

Much of the early pioneering was by British designers, including James Wharram, who craved simple and care-free long distance cruising.

Olympic canoeists Francis and Roland Prout, on the other hand, were initially focussed on the speed potential multihulls offered.

Inspired by French sailor Eric De Bisschop’s pioneering voyage from Hawaii to Marseille on his 38ft double canoe/catamaran Kaimiloa in 1937/8, Wharram was keen to further prove the seaworthiness of the concept.

In 1953 he designed and built a plywood 23ft 6in ‘double canoe’ which he sailed across the Atlantic to Trinidad two years later.

For the return journey he built a 40ft version on the beach in Trinidad, reputedly with help from Bernard Moitessier, before sailing first to New York and then to Ireland in 1959.

This was the start of a prolific career that has seen him design dozens of distinctive V-hull double-ended catamarans, from 13ft to more than 60ft.

He has sold more than 10,000 sets of plans, with the bulk of boats completed built by enthusiastic amateurs, and still sails his creations at the age of 90.

Meanwhile, having successfully trialled a pair of canoes joined together with cross beams, with a small rig added, the Prout brothers started designing purpose built small racing catamarans.

Their first two won almost all the races they entered, drawing plenty of admiration.

The third, the 16ft 6in Shearwater lll in 1956, was equally successful and developed into a large racing class with more than 1,500 boats built.

Eventide

1957

Shallow draught and the ability to con dently dry out open up a huge number of possibilities for Eventide owners. Credit: Rupert Holmes

Many of the new generation of small yachts were bilge or triple keel designs that allowed for an inexpensive drying mooring and easy beaching to scrub off and antifoul.

Although twin keels had been around since the Lord Riverdale began experimenting with them in the 1920s, only a handful had been built before the 1950s.

Maurice Griffiths, long-running editor of PBO’s sister title Yachting Monthly, was also a prolific yacht designer with a passion for making sailing affordable and bringing it to a wider audience.

His 24ft and 26ft plywood Eventide designs of 1957 were aimed squarely

at aspiring cruising sailors.

While many were professionally built, most were constructed by resourceful and ambitious owners.

The distinctive raised topsides significantly increased the accommodation volume, there was relatively good headroom, adequate stowage and space for four berths.

A fin keel option was available, but almost all Eventides are the triple keel version, with owners valuing shallow draught and the ability to dry out at low water over better windward performance.

Although nowhere near as many were built as the tens of thousands of plywood dinghies, some 2,000 sets of Eventide plans were sold and it’s believed that at least half that number of boats have been built.

Before the war the building of such large numbers of sailing boats of any description, yet alone a four-berth yacht, would have been unimaginable.

Pionier 9

1959

Pioneer 9 was among the first yachts designed specifically to be built in fibreglass. Credit: David Harding/Sailing Scenes

Most of the early fibreglass yachts tended to be developments of wooden designs, with the mould taken off an existing boat.

However, this 30ft EG van de Stadt design from 1959 was among the first production yachts intended from the outset for production in the new material.

Hull and deck construction was by Tyler, with Southern Ocean Shipyard in Poole responsible for the fit out and completion.

It’s easy to assume the Pionier 9 also broke the mould with its separate fin keel and spade rudder.

However van de Stadt had been drawing yachts with fin keels and spade rudders throughout the 1950s and was already very familiar with the concept.

The capabilities of the Pionier 9 were proven beyond doubt 12 years after it was first launched, when Nicolette Milnes-Walker became the first woman to sail single-handed across the North Atlantic, completing the voyage from Pembrokeshire, Wales, to Newport, Rhode Island in 45 days.

The advent of fibreglass

The 1914 yawl Cooya was an early bene ciary of breglass when her decks were sheathed. Credit: Kass Schmitt

The technique to mass produce glass strands was discovered accidentally in the early 1930s, and by 1942 an early polyester resin had been developed, allowing structures to be made of this new material.

It was initially slow to gain acceptance in the boat building world, but in 1952 two pioneers on opposite sides of the English Channel put the material to good use to give new life to older yachts.

In Kent, Edward (Eddie) Tyler owned Cooya, a 40ft 1914 Lynton Hope-designed yawl.

He had already been using fibreglass for prefabricated structures in his building business and figured the material could be used to protect Cooya’s ageing decks.

After careful drying he sheathed them in polyester and glass, which worked for 50 years until this was replaced with an epoxy based system in 2003.

Tyler subsequently formed the Tyler Boat Company, which moulded 45 different designs for boatbuilders across Europe from the late 1950s to 1980.

He also sold many bare hull and deck mouldings for owners to fit out themselves.

On the other side of the Channel, Eric Tabarly’s father was planning to scrap the family’s yacht on which Eric had spent most of his childhood holidays – the wooden hull was well past its best, with the lead in the keel the only remaining element of value.

Not wanting to see the boat destroyed, Eric, who was then in his early 20s, took on the project, using the original hull as a mould from which to build a new one in fibreglass, before transferring the keel and fittings from the old boat. The revitalised Pen Duick is still with us more than 60 years later.

As published in the February 2019 issue of Practical Boat Owner magazine.