After a succession of GRP and ferrocement boats, Max Liberson finally fell in love with a wooden 1930s gaff cutter, as told to Ali Wood.

I don’t own Wendy May, she owns me. I’m just the custodian. She was built for an army officer in 1936 by Williams & Parkinson in North Wales. Their brief was to ‘build a boat that can sail around Brittany and dry out on legs’.

She has a frame or rib every 6in and is fantastically strong – so she easily meets that brief.

It’s the most magical thing you can do, sailing an old classic boat – but I’ve owned many boats beforehand.

The brass plaque by yacht builders Williams and Parkinson, Deganwy, North Wales

Back in 2010 I was offered work in Gallions Point Marina in London.

I needed somewhere to stay and so bought a broken-down ferro-cement schooner for £1,500.

The boat, called Gloria, was in a terrible condition. In the sunlight you could see right through the coachroof. She’d been built too heavy and floated 6in below the waterline.

She was never going to be a good boat.

The first time I went hard astern, the engine moved, but not the boat. Little things like that are a dead giveaway…

When my job finished I stepped the masts and put a new coachroof on. I managed to get her round to Battlesbridge, near Southend-On-Sea, and met my good friend Edmund Whelan, who’d just retired from the RYA where for 24 years he’d been working as a legal expert.

He was looking for an adventure, and during a test sail, he turned to me and said: “Very well, Max, I think she’ll do the job.”

“What job?” I asked.

“Get her down to the Canaries and we’ll go across the pond. It’s not like you’re doing anything else!”

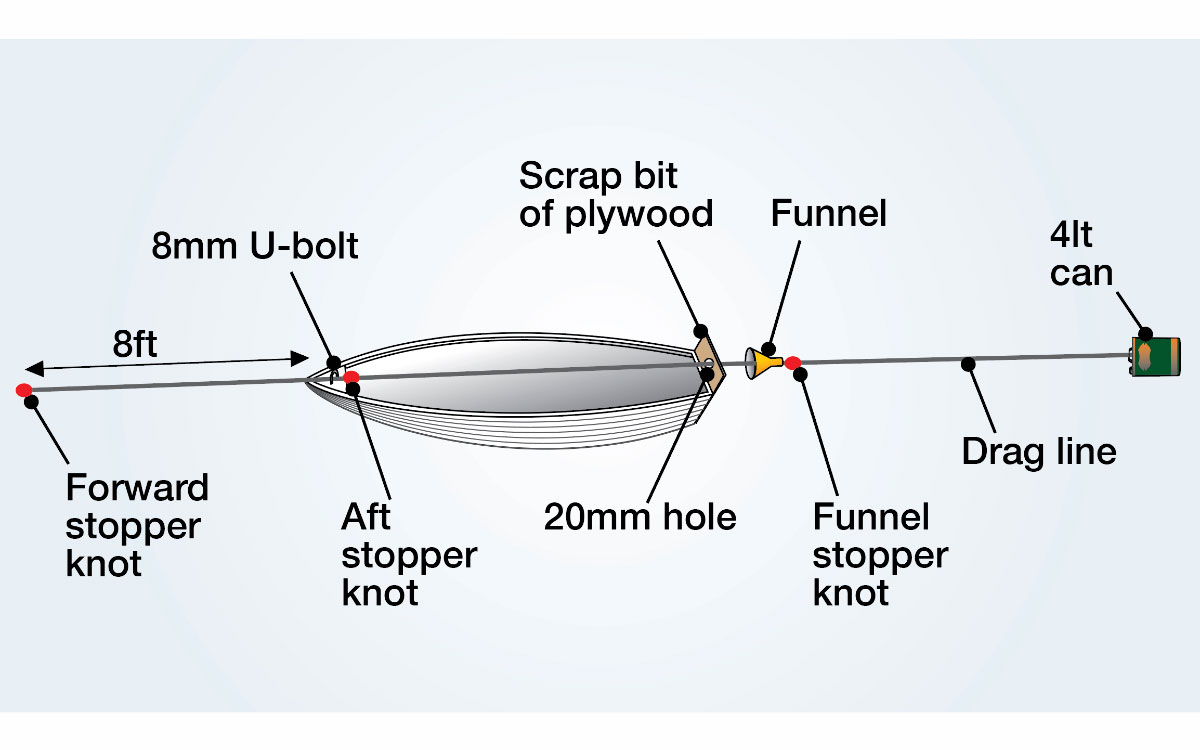

DIY anti-surf device for towing a dinghy

I’ve owned my dinghy for 30 years and the friend who sold it to me was killed in a motorcycle…

Home before lockdown – 26ft classic boat delivery from Essex to South Wales

Due to family commitments I found myself having to move to Wolverhampton late last year from West Sussex. I’ve never…

Crossing the Atlantic on a ferro-cement yacht

I worked hard on Gloria and got her ready by September. Edmund helped me sail her down to the Solent and we waited for a weather window to cross Biscay.

Next, we sailed to Porto Santo in Madeira.

In the Canaries I was joined by another crewmember – Jack ‘Captain Blood’– who I’d recruited from the toilets at the Jolly Sailor in Las Palmas.

The three of us sailed slowly to the Caribbean with a stop in the Cape Verdes.

After a sedate but successful crossing (we didn’t sink), Edmund joined some other friends on a yacht called Stealaway, Jack went off to Brazil and my girlfriend came out to help me cruise the Windward Islands.

It was while at anchor in Tyrrell Bay, Carriacou, that Gloria began to sink.

We hauled her out and took her to a boatyard where one of my new friends happened to be the manager.

They washed her off and found you could put an entire arm up the hole in the keel, which was filled with Essex mud! I put some plywood underneath, cut a hole in the compression post and poured in three large buckets of sloppy mortar that filled up the void.

While I was at it, I removed the big old prop because the engine didn’t work anyway.

My girlfriend flew back home.

Single-handed, I sailed Gloria to England. It took 53 days to get back. It was a lot of fun – I met a lot of brilliant people along the way and wrote a book about it: The Boat They Laughed At.

How I taught myself to sail

I sailed 10,000 miles on my Trapper 500 Sarah, but eventually found myself wishing for a heavier boat

Gloria wasn’t my first boat. In fact, I’ve been knocking around boats since 1976.

I was originally a fisherman in Plymouth, but when EU legislation made it harder to fish in 1984 (forcing us to throw tons of dead fish back into the sea) I moved to London and became a motorcycle dispatch rider.

I had such a yearning to be afloat that in 1992 that I bought a yacht and taught myself to sail, first at Putney, then Thurrock Yacht Club in Grays, Essex.

In 1999 I passed my RYA Yachtmaster Offshore practical, and proceeded to sail a whole range of boats: a 20ft Hurley, a Halcyon triple keel, followed by an Atlanta 28 bilge keeler, which I sailed to Norway in 2004 with my then-wife.

We got caught out in the 2004 midsummer storm.

The boat survived but the marriage didn’t.

My wife was a keen sailor, but that kind of weather either makes or breaks your relationship. We arrived in Eyemouth after five brutal days, then sailed back to Thurrock Yacht Club.

Things were never the same after that, and we separated soon after.

I part-exchanged the Atlanta 28 for a faster Seal 22 – a lift-keeler – then finally managed to buy Sarah, a Trapper 500 that had been in the club since new and I’d always desired.

I started doing yacht deliveries and really enjoyed racing the Trapper.

I didn’t like the rudder, though. It was a spade rudder, and as the boat heeled it became harder and harder to hold the helm. Eventually the rudder would come out of water and Sarah would round up.

For a while, I was just doing deliveries and then I enrolled on a RYA Cruising Instructor course, which is where I met Edmund Whelan, who was the only other pupil.

We both passed and worked together on several yacht deliveries.

Transatlantic in a Trapper 500 – I needed a heavier boat!

After I returned from the Atlantic circuit on Gloria I was offered work in Portugal, rebuilding the hulls of a large trimaran.

Firstly, I delivered the trimaran to Portimão, but after a row with the boatbuilder – who was supposed to be doing the work – I became the project manager.

With the help of Paul Wells, who I found in the UK, we set up a boatyard, hired staff and even made our own specialist equipment.

Paul had many years’ experience in glass-fibre and carbon-fibre work and I learnt many new skills.

After two years we completed the original trimaran project and the owner was so happy with it, he wanted the rest of the vessel rebuilt in carbon-fibre foam sandwich.

But I had itchy feet so I handed over to Paul, and returned to the UK to sail Sarah back down to Portugal, where I hauled her out to make a new transom-hung rudder.

Just when I finished, and was wondering where to go next, I got a message from an old friend to say he’d found me some self-tailing winches, which I’d been after for a while.

“But there’s a snag,” he said. “They’re in the Caribbean – you’ll have to come and get them.”

So once more I had a blissful sail across the Atlantic and back.

The new rudder worked brilliantly.

Altogether I sailed 10,000 miles in Sarah with no breakages. She did an amazing job, but I got fed up with being constantly thrown around. I missed the comfort of Gloria – who weighed 16 tonnes – but wanted a boat that could sail in light winds; a heavier, more comfortable boat, where you don’t feel like you’re in a washing machine.

When not to trust your first instincts

The first time I met Wendy May was in 2015 at the Maldon Regatta with yachting journalist Dick Durham. The rain was falling gently and we jumped aboard at 4am. We turned on the ignition. Flat battery. We didn’t have long to make the first tide.

“Well, Dick,” I said. “With all the sailing miles we’d done between us we ought to be able to sail her off the mooring.”

“I’ll have a crack if you will,” he replied.

He hauled up the main. Big mistake; all she would do was turn into the wind in the opposite way we wanted to go.

He was desperately trying to get the headsail up in the dark with no torch. We got round the starboardhand marker on the wrong side – it was really shallow stuff – but then Dick managed to raise the headsail and we started going downstream, like we wanted.

God, it was hard.

That little incident didn’t enamour me to Wendy May.

“You’ve got a boat that won’t steer,” I said to Dick.

“She will if you treat her right. If you don’t, she won’t,” he replied.

In the end, with all the sails up, we made it to a mooring near Brightlingsea. We charged the battery in a friend’s motorboat and got the engine working.

The next day we took part in the race. It was very light winds, and we didn’t do too well; those Colne smacks went steaming past us – their bowsprits longer than the boats themselves – but it was a sight to behold and I fell in love with the gaff rig and Wendy May.

The following year, Dick wanted to recreate a voyage on his own boat that he’d made in the Thames Barge Cambria, which he’d been a mate on in 1968 for her very last cargo delivery to Felixstowe.

There were two snags with this voyage: the first was that the trip had to be done in May, the other was it was from Canvey island to the Humber and back.

Dick couldn’t get anyone else to crew, so I got the job.

Conditions were mixed but mostly cold, and confirmed my first impression of Wendy May – she was the perfect boat!

Soon after, Dick found another boat, Betty 2. Slightly smaller than Wendy, she was a gaff-cutter with a lifting keel that he could keep on the mudflats where he lived in Leigh-on-Sea.

He was sad to let go of Wendy May, and fed up with all the tyre-kickers. He caught me stroking her at the yacht club and said to me, “Max, just make me a stupid offer.”

I did, and he said yes.

The problem was, I’d just returned from the Caribbean and started a business, so didn’t have any money.

“Pay me when you can,” said Dick.

We shook hands and that was it – I took delivery of Wendy May at Island Yacht Club in Canvey Island.

My first single-handed sail was coming out of Maldon and down the Blackwater. I missed the afternoon tide so caught the evening one.

There was hardly any wind but Wendy May ghosts on a zephyr.

I saw Dick’s old barge, the Cambria, newly rebuilt. I knew he was on board having been invited to sail on her once more. She was at anchor and I slipped alongside on the off-chance that Dick was still awake, but he’d turned in; it was very late.

However, the man on anchor-watch said he’d tell him I stopped by to say hello. Then he added: “That’s what it’s all about – seeing you ghost down the Blackwater like that.”

I could see his point; it was a beautiful night that would have been wasted sleeping.

Wide decks · nice motion · slow to tack

My dog Luna loves Wendy May, with her wide decks, much more than she did the Trapper. It’s usually just the two of us sailing and she has no fear.

Sometimes my new wife, Eva Maria, also comes with us, but that’s only when it’s sunny! There are no safety rails but Wendy May has a nice motion so you don’t miss the illusion of security you get from little stanchions.

I like having two full-sized bunks up for’ard, and the Taylors paraffin heater is just lovely at night, especially if it’s raining. You can sit all snug and cosy reading a book, and look up at the stars through the skylight.

I don’t miss TV or computers at all.

Wendy May has a huge bowsprit, and I love her motion in the water. I normally just rig the gaff, the staysail and the working jib. I have a balloon jib for fine weather. I’ve discovered that it’s best to reef the big mainsail early, as it’s surprising how little sail area Wendy needs to get her six tonnes moving.

The thing about the gaff rig is it gives you the chance to have a lower centre of effort. With more sail area lower down you can generate a lot of power.

She’s not so good going to windward but then again, neither am I!

She’s also slow to tack – but that’s not important for long-distance cruising.

I was invited to the Southampton Boat Show last year to represent the Old Gaffers Association.

There were a few owners’ associations there and we all wanted to get across the message – among all those expensive yachts – that you don’t have to be a millionaire to own a boat.

It was brilliant.

I met all these wonderful people, some of whom already knew Wendy May. One lady had spent a week on her back in 1965. She came on board and choked up – said it was the best week of her life!

The thing about classic boats is that you feel all the people who’ve worked on the boat before you; all the people down the ages who’ve added their own touch. It’s like sailing around with their best wishes.

I love the Old Gaffers. I’ve finally found my niche. I think I’ve been a secret Old Gaffer all this time!

■ You can read more about Max’s adventures in his book The Boat They Laughed At, which is available on Amazon.

Why not subscribe today?

This feature appeared in the August 2020 edition of Practical Boat Owner. For more articles like this, including DIY, money-saving advice, great boat projects, expert tips and ways to improve your boat’s performance, take out a magazine subscription to Britain’s best-selling boating magazine.

Subscribe, or make a gift for someone else, and you’ll always save at least 30% compared to newsstand prices.

See the latest PBO subscription deals on magazinesdirect.com