Margaret Norris charts the incredible role of Robert FitzRoy in the development of the Met Office

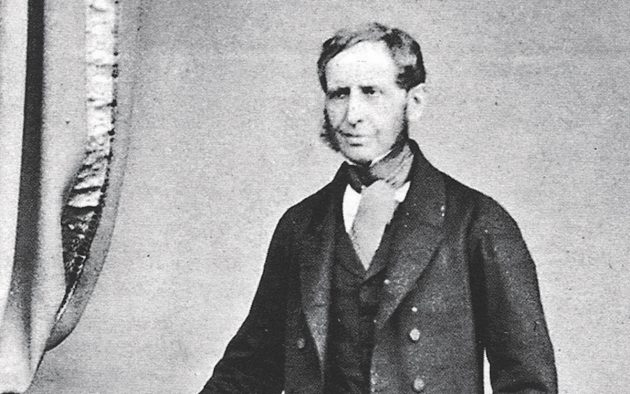

Robert FitzRoy/ Alamy Stock Photo

As sailors we’re used to checking the weather before any journey from the hundreds of weather providers including the Met Office. Give a thought therefore to the ships of the past who set out with incomplete and incorrect charts and no weather information at all and yet managed to circumnavigate the world. Sir Francis Drake took three years to do it in the 1500s and Captain Cook did it three times in the 1700s collecting data and improving charts as they went. But thousands of ships were not so lucky and one of those was the Royal Charter.

In 1859 she’d sailed all the way from Melbourne in Australia with more than 500 people aboard looking forward to seeing British shores again when she was caught in a storm just off Anglesey. In desperation her captain threw out her two anchors to try to steady her in the heavy seas, only for them both to break and the ship to get blown onto the rocky shore. Only 50 people survived.

The tragedy sparked the beginnings of the science of forecasting at the fledgling Met Office and the great man who was to shape it in its infancy was master mariner Robert FitzRoy. He’d already captained the Beagle, which took Charles Darwin to South America doing research for the controversial On The Origin of Species.

During the voyage FitzRoy had meticulously recorded the weather every day noting barometric pressure, temperature and wind direction as well as accurately charting coastlines, so he was the ideal man for this very new job.

His initial responsibility from 1854 as Meteorological Statist at the Board of Trade was to collate the weather reports contained in British shipping logs to produce average wind speeds and directions for the most common shipping routes around the world. But the wreck of the Royal Charter moved him to provide storm warnings to shipping to prevent loss of life. He set up weather stations around Britain’s coast and it was their job to take weather measurements at the same time every day and then send them, via the newly invented Morse telegraph, to a team of clerks in London who transposed them onto charts. This was the beginning of the synoptic chart, a way of reducing lists of figures and measurements to more understandable lines on a map. If a storm was reported in Scotland, for example, he’d notify all the other stations to run up a system of cones and drums on a flagpole at the coast, which ships could see and use to take avoiding action.

He then stepped over the very fine line between weather reporting and weather predicting, which he named ‘forecasting’. Even though the science wasn’t fully understood, he believed he could judge when a storm was coming and warn shipping accordingly. But upon his death in 1865, the Board of Trade decided he’d overstepped his remit with forecasting – so closed down his department.

Within a short space of time complaints started coming in from the owners of merchant vessels, naval captains and fishing fleets, all of whom had come to rely on FitzRoy’s forecasts which, when analysed after his death, were found to be 70% accurate. The Board of Trade came to its senses and the forecasting was on the agenda once again.

Within 100 years weather satellites were being launched for the first time and today the Met Office analyses 215 billion weather observations from all over the world every day. FitzRoy would be proud.