Cruising legend Jimmy Cornell reflects on his many years of boat ownership and his quest to create the best liveaboard boat for bluewater adventures…

Every voyage starts with a dream and for me it goes back a long while to when I was a little boy and wanted to become a sailor when I grew up. That dream came true a quarter of a century later. At the time I was working in the BBC External Services, our children Doina and Ivan were six and four, and life seemed to be settled and the future promising.

The BBC Yacht Club had a 40ft Lion class sloop on which I spent weekends sailing off the south coast and across the Channel. It didn’t take me long to decide that sailing was what I really wanted to do.

I felt that there must be more to life than having a successful career, which could wait, whereas a world voyage with the family could not. I knew that it was a crazy idea, but fortunately Gwenda was a passionate traveller and, to my surprise and relief, agreed and gave her full support to the idea.

Our main concern was the children’s education. Gwenda, who had a degree in pharmacy, completed a two-year evening course in education and taught for one year in their school to gain the necessary experience.

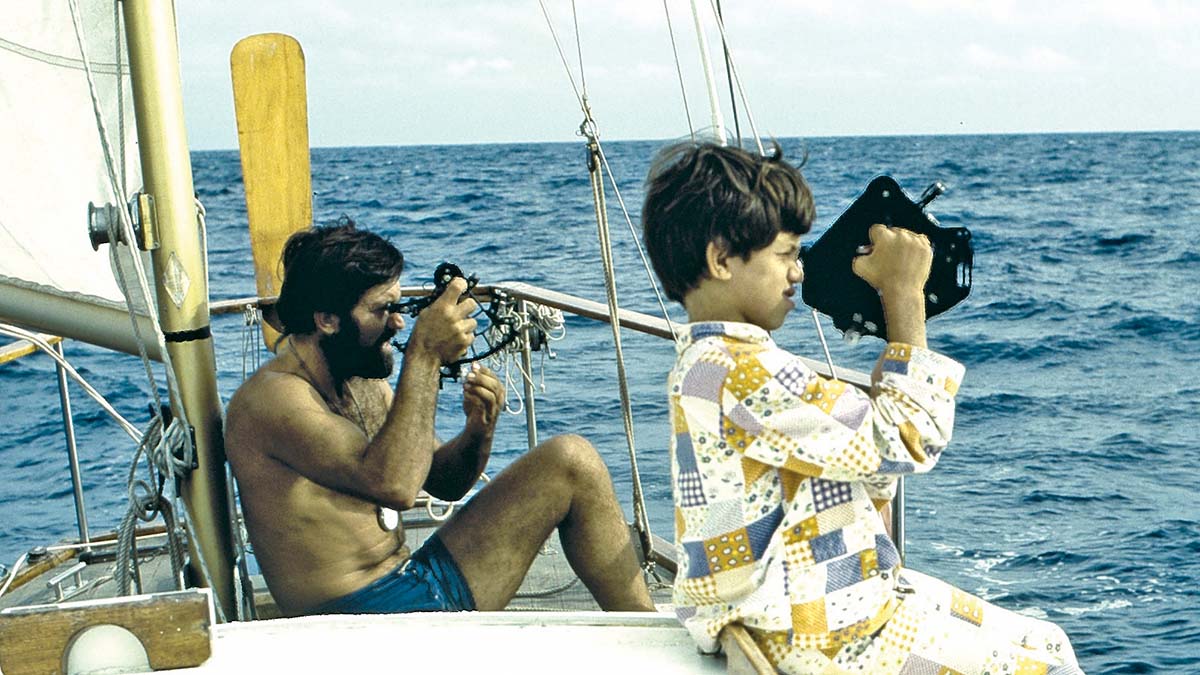

Meanwhile, I took a course in seamanship and navigation, and started looking for a suitable boat. As we couldn’t afford even a second-hand boat, with a loan secured on our small property, we managed to raise enough funds to order a 36ft fibreglass hull.

Article continues below…

Jimmy Cornell asks how much safer has sailing actually become in 40 years?

Without doubt, safety has been the biggest improvement to long-distance cruising over the last 50 years. This is my own…

Jimmy Cornell boat survey reveals how much sailing has changed in 40 years

‘During the past four years I have sailed through some of the major crossroads of the cruising world: Rhodes, Gibraltar,…

Liveaboard boat preparations

One day in spring 1973 a gleaming white hull was wheeled into a large shed in London’s Royal Albert Docks. As I looked over the side into the void below my feet, I was struck by the magnitude of my undertaking. My feelings were not helped by seeing the many unfinished hulls, mostly ferro-cement, spread about the huge shed.

They obviously belonged to other hopeful dreamers just like myself. But it was a friendly atmosphere, and I could always get help or advice from someone who knew more than I did, which was close to nil.

This was by far the greatest challenge I’d ever faced, but its sheer enormity infused me with the determination to take it on. Using every spare hour and weekends, slowly Aventura started taking shape.

The partly-finished Aventura is launched in 1974

Although only partly finished, in July 1974 she was launched and I took her on a test sail in the English Channel. That maiden voyage showed up all the mistakes I’d made but, as she was mostly unfinished, I could easily put them right. By the following spring we were ready to leave.

I went to see Peter Udell, the head of the BBC East European Service, to hand in my resignation. He knew of my plans, and insisted on accepting it only on a temporary basis and asked me to continue my weekly short-wave programme.

Called ‘Aventura’, it consisted of a mixture of adventure stories and pop music, and was a great success among an audience living under a strict communist dictatorship.

The unexpected offer was a great relief, as the boat had swallowed up all our savings and it meant we’d be able to count on a weekly fee of £28. This may not sound much now, but in the following years it covered all our living expenses.

Peter also suggested that I should look out for original subjects and interview local people involved in original projects. It was an interesting task, and throughout our voyage I sent tape recordings to the relevant BBC World Service programmes on a wide variety of subjects.

That was the beginning of my freelance career, and marked a significant turning point in my life. Looking out for original material became a permanent quest, not only for my radio work, but any other journalistic work.

The survey conducted in the South Pacific, and referred to in my two previous reports, was a first example. Its results were published in all leading sailing magazines in the world, Practical Boat Owner foremost among them.

A family-friendly liveaboard boat?

After a year spent in the Mediterranean getting used to this new life, we crossed the Atlantic, spent a year exploring the Caribbean and US East Coast, transited the Panama Canal, criss-crossed the South Pacific from Easter Island to Papua New Guinea and Tuvalu to Australia, cruised the entire Indonesian archipelago from Torres Strait to Singapore, and crossed our outward track via the Suez Canal.

The planned three-year voyage had stretched into six. We would have spent even longer, had Doina not reached the age where we knew that she had to resume formal education or we might jeopardise her future.

In 1981 we returned to London, Doina and Ivan, by then 14 and 12, returned to school, and quickly reintegrated into life on terra firma. With no further sailing plans, Aventura was sold and I rejoined the BBC.

Throughout our 58,000 mile-voyage Aventura proved to have been the best liveaboard boat I could have chosen. In spite of her modest length, she was a comfortable and safe home.

Tylers had done an excellent job in building a very strong hull, as I found out when we ran aground on a reef in the Turks and Caicos Islands and spent several hours pounding on a large coral head. Lifted on the rising tide we found no serious damage to the hull except some surface scratches.

When the time came to choose a successor, in which I also planned a world voyage, I had many ideas based on my previous voyage and also on the findings of follow-up surveys dealing with the essential features of a long-distance cruising boat.

Custom-designed liveaboard boat

As there was nothing on the market that came close to what I had in mind, I decided to set down all the desirable features and have a naval architect turn them into a basic design. I contacted Bill Dixon, a young naval architect, who was already known for his original approach to boat design.

He agreed with my concept and produced the plans for Aventura 40, a revolutionary design that included all the essential features I insisted upon.

During the three years we’d spent in the South Pacific I’d heard of several boat losses due to navigational errors, groundings or collisions. Therefore I wanted the new Aventura to be as strong as possible, which in those days meant a steel hull.

Aventura II had a retractable wing keel and twin rudders

In some of my decisions I was influenced by the findings of my initial survey, among them the importance of watch keeping. I knew that meant good cockpit protection, and having had that essential feature on the first Aventura I wanted to have it again. An overall length of 40ft, which I regarded then as ideal, had been easily decided upon.

As I regarded shallow draught to be an invaluable advantage when cruising, we agreed on having a retractable keel. Fully retracted, the hydraulically-operated keel passed through a box, which ended at deck level.

Inspired by the Australian victory in the latest America’s Cup, I asked Bill to add two large wings to the keel, which greatly improved the boat’s stability. The draught with the keel fully down was 1.8m.

To keep the shallow draught with the keel retracted to under 1m, Aventura II had twin rudders – something I believe had never been attempted on a cruising boat of that size before.

The most revolutionary feature was my idea of having two engines. Besides providing a permanent safety backup, as each engine could power the boat on its own, the main advantage was that one engine, fitted with a powerful alternator, acted as a generating unit.

Both Perkins 28hp engines had MaxProp folding propellers, which combined with the two rudders significantly increased the boat’s manoeuvrability. The rig was a standard cutter with a Hood in-mast furling mainsail, which had become popular in those days.

An eye-catching feature was the hard dodger, which not only provided perfect cockpit protection, but was also attractive and gave the boat a beautiful overall look.

The interior was quite unusual as the main accommodation was located in the stern, where a large table and U-shaped settee on a slightly raised platform, provided a good view to the outside. It was a feature that I greatly missed on Aventura III, but made it the first priority on Aventura IV.

Two cabins, separated by the keel box, occupied the centre of the boat. The starboard cabin had a double bed, while the port cabin had two superimposed bunks with high sides that made them very comfortable at sea.

Aventura II in the spectacular Marquesas

A passageway through that cabin led to the forepeak, which was reached through a massive door. Provided with submarine-type clamps, it turned the forepeak into a sacrificial collision zone. This was a service area with a full-size workbench, a diving compressor and gear, two inflatable dinghies, spare anchors, ropes and fenders.

Sadly, this highly functional boat had one great disadvantage: designed to have a displacement of 12.5 tons, when she was weighed prior to launch it came in at 17 tons. The builder had taken me at my word to produce a solid boat, but I ended up with a mini battle cruiser.

She was slow in light airs, but stable and gentle in a breeze. Her versatility proved to be a great advantage in the first round-the-world rally. By the time she was sold in 1995 she had sailed over 40,000 miles.

Lessons learned from owning liveaboard boats

The ARC and various other rallies were keeping me busy in the late 1990s but the temptation of a new world voyage was becoming increasingly irresistible.

Whenever it happened, I wanted it to be open-ended and this would define my next, and quite probably, last boat. The choice of the new Aventura was quite simple, as I knew exactly what I wanted: a fast boat that was easy to sail short-handed, and would take me safely to anywhere in the world.

A valuable lesson I’d learned when working on the first Aventura, was to listen to those who know more than I do. In this case it was Erick Bouteleux, a good friend I’d met on my first voyage. On his return home, he became the agent for Ovni Yachts on the French Riviera.

Aventura III in Antarctica

All Ovnis were aluminium and shared a number of features: hard chine, flat bottom, integral centreboard and folding rudder. I set my eyes on the Ovni 43, which had a displacement of 9.5 tons and was known for its good sailing performance.

After my previous experience, having a proven design produced by a reputable builder was a great attraction. However, after the luxury of designing the interior of my second Aventura, being faced with the narrow choice of the standard Ovni layout was the price to pay.

Erick managed to persuade the owner of Alubat, the Ovni builder, to make a few exceptions in my case. What turned out to be the best among them was Gwenda’s decision to go to Ikea, buy two comfortable leather armchairs, and insist on having them fitted in the main cabin. I have never sat in a more comfortable chair on any boat since.

Comfy leather armchairs on Aventura III

After the frustrations, and costs, caused by the maintenance of the previous Aventura’s steel hull, Aventura III had an unpainted hull. Besides its strength, the greatest advantage of aluminium over any boat building material, is that it naturally forms a durable oxide layer on the exposed surface that prevents further oxidation.

In 2010, when I decided to sell her, having sailed 70,000 miles and 13 years after she had been built, it took me less than a couple of days to bring her hull into pristine condition.

Aventura III is very close to my heart and I remember the many wonderful moments I sailed on her, the highlight of them being our voyage with Ivan from Antarctica to Alaska. That was followed by my third circumnavigation.

Aventura III’s hull in pristine condition after 13 years and 70,000 miles

At that point I could say that I’d sailed to all the places I’d wanted to see, and more. There was, however, one name that was missing, and that was the Northwest Passage.

Three years after having sold Aventura III, and fortunately still in good shape at 73, I felt I should still be able to take on one more ambitious project and attempt to sail through this most challenging goal in the history of exploration.

Furthermore, I realised this would be my last chance of creating my long-sought ideal liveaboard boat. For much of my sailing life I’d been trying to find out if there was such a thing.

While each of my previous boats had several original features, which I’d not seen elsewhere, this was a unique opportunity to bring them all together and add some new ones. It was a chance I shouldn’t miss and I knew precisely what I wanted: a strong, fast, comfortable, functional and easily handled boat, perfectly suited for all seas and all seasons.

Arctic challenge

Still convinced that only aluminium could be the answer, I contacted the Garcia boatyard, at that time regarded as the best builders of aluminium boats in the world. I was fortunate in being able to infect with my enthusiasm Stephan Constance, its CEO, and Olivier Racoupeau, one of France’s top naval architects.

I told them I wanted to keep the best features of my previous Aventura, such as an unpainted aluminium hull, integral centreboard, shallow draught and cutter rig. To this I wanted to transplant to a monohull the almost all-round visibility that I found so attractive on catamarans.

As far as I knew, a deck saloon had never been attempted before on a yacht with an integral centreboard, because the added height and weight might affect its stability. The designer solved this problem by settling for a low profile and fulfilled my request: a spacious saloon with 270° visibility without compromising either the stability or the looks of the new Exploration 45.

Aventura IV flying the Parasailor in the Northwest Passage

Safety, however, was the first priority. Aware of the hazards of sailing in high latitudes, the hull had to be very strong to withstand collision with ice. It should also have watertight collision bulkheads, both fore and aft.

The two aluminium rudders, although protected by skegs, should have an added protection by having a crumple area incorporated in the upper section of each rudder blade. In case the rudder was pushed upwards in a collision, the sacrificial section, made of light composite material, would absorb the shock and avoid any damage to the hull.

Because of my concern for the environment I wanted the new Aventura to have as low a carbon footprint as possible. Unfortunately none of the hybrid engines, that were available at that time, were suitable for my plans. I made up for that by covering my energy needs from renewable sources, with a combination of solar, wind and hydro generation.

On the advice of the designer, I agreed to a fractional rig with a full batten mainsail and Solent jib, which he assured me made for a more efficient configuration. I also had a staysail for stronger winds. Occasionally they were used together, as on a cutter, usually with the Solent partially rolled up.

The mast was also much better stayed than on my previous boat and, due to the swept-back spreaders, the lower shrouds were not obstructing the side deck.

Aventura IV caught in ice

Ice conditions in the Northwest Passage in 2014 stopped us from completing our attempt at making a transit from east to west. Rather than wait until the following summer, I decided to improve our chances by attempting to do it from the opposite direction.

We headed south from Greenland, transited the Panama Canal and, in the summer of 2015, passed through the Bering Strait and successfully transited the Northwest Passage by that roundabout way. Aventura IV fulfilled all my expectations on this challenging passage and I doubt I could have done it so safely and easily in any other boat.

She showed her forte when we got in a critical situation caught in ice, and got us out of trouble behaving like a mini-icebreaker. She was, however, just as much in her element when we cruised the Bahamas. A boat for all seas and all seasons indeed. My quest for an ideal liveaboard boat had been achieved.

Unexpected challenge

In 2017, with no plans for any more voyages, I decided that Aventura IV was not the kind of boat to spend the rest of her life sitting idly in some marina. She was sold to a sailor who was planning a similar Arctic voyage. As for me, sadly, I had to admit that this was indeed the end… or so I thought.

Historic anniversaries have always had a fascination for me, be it the 500th anniversary of the voyage of Christopher Columbus to the New World in 1992, or that of Vasco da Gama’s around the Cape of Good Hope in 1998.

I celebrate both of those events by organising rallies along their historic routes. The approaching anniversary in 2022 of the first round the world voyage was an opportunity I was not prepared to miss – not by organising a rally for other sailors, but by doing something special for myself.

Cornell’s voyages from 1975 to 2021

The first circumnavigation of the planet continues to be attributed to the Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan. In fact, the person who should be credited with that achievement is the Basque sailor Juan Sebastian Elcano.

He sailed with Magellan from the start in 1519, took over the leadership of the expedition when Magellan was killed in the Philippines, and completed the voyage in 1522. This is how the idea of my Elcano Challenge was born: to complete a circumnavigation along the same route by a fully electric boat in memory of Elcano. ELectricity. CArbon. NO.

The aim was to conceive a sailing boat using no fossil fuel for propulsion or electricity generation, and rely exclusively on renewable sources of energy. The essential factor of electric propulsion on a sailing boat is the ability to generate electricity not just by passive means (solar and wind), but primarily by the movement of the boat.

That means a potentially fast boat under sail, whether monohull or multihull. Ideally, such a boat should also have enough surface available to display several solar panels.

Aventura Zero and her Elcano Challenge livery

As the time was too short to start from scratch, I decided to do it on an Outremer performance cruising catamaran. Xavier Desmarest, the CEO of Outremer, reacted enthusiastically to my idea and agreed to make all the necessary modifications to their standard Outremer 45.

The most important element of my concept was to find an efficient way of generating electricity while underway. This led me to the Finnish company Oceanvolt, which had developed an ingenious system based on their ServoProp variable pitch propeller.

The software-controlled propeller could automatically adjust the pitch of the blades to provide an optimal level of either regeneration or power output.

With a ServoProp capable of generating an estimated 500W at 6 knots and 800W at 8 knots, plus Aventura Zero’s solar panels with a capacity of 1300W, all electricity needs would be covered without the need for a separate generator.

Under normal sailing conditions, that should be enough to charge the two propulsion battery banks of 28kWh each, as well as a 2.4kW service battery.

A proper test

Although Outremer insisted that I had a backup diesel generator, I refused, as I was determined to prove that long-distance cruising with a zero carbon footprint was possible and sustainable.

I hadn’t had a diesel generator on any of my previous boats and for electricity generation relied on the main engine, supplemented later by solar panels, wind and hydro generator.

I tested such a system on my return from the Northwest Passage when the engine failed shortly after leaving Greenland. We managed to sail over 2,000 miles to the UK relying primarily on a Sail-Gen hydro-generator that covered all our requirements: autopilot, instruments, communications, electric winches and toilets, and arrived at Falmouth Marina with fully charged batteries.

At my request Aventura Zero’s sail plan was improved with some performance features, such as a self-tacking Solent jib and a rotating mast. The boat was launched in La Grande Motte, in the south of France, in September 2020, and within a month we were on our way to Seville and the formal start of this special voyage.

The night after our arrival, a thunderstorm of apocalyptic force broke over the city. Lightning struck the dock behind us and the power surge put the entire Oceanvolt electrical system out of action. It took two weeks to have it all replaced and thus delayed our departure for the Canaries.

By the time we got to Tenerife, the Covid pandemic was raging throughout the world, with several countries on our proposed route closed to visitors. My crew said they were reluctant to continue, and I agreed.

Resuming the voyage was indeed looking increasingly risky and I had to decide whether to stop in Tenerife and continue the voyage later, or return to the boatyard and have a number of teething problems put right, among them the regeneration system.

The most important job was to replace the port side Gori folding propeller with an Oceanvolt ServoProp. Having that arrangement seemed to make sense from a safety point of view, but turned out to have been a mistake as on most occasions we’d not been able to generate sufficient electricity with only the starboard ServoProp, despite the boat’s excellent sailing proficiency.

Zero emissions liveaboard boat

Still, I’m very pleased that we’d completed each of our offshore passages with zero carbon emissions. On the last leg from Tenerife to France I carefully monitored the systems, keeping a record of both the rate of regeneration and overall electricity consumption.

On that 10-day nonstop passage all our electricity needs were covered by onboard regeneration. We set off with the battery bank at 95% capacity and arrived with 20%, with enough left in the batteries for an emergency.

That 1,540-mile winter passage had been ideal in putting the concept to a proper test, as we encountered the full range of weather from calms to gales with sustained winds of over 40 knots. On that level, the test had been successful, albeit at the cost of a sustained effort to keep domestic consumption to a minimum.

One area in which a compromise would be acceptable is to occasionally charge the batteries when stopping in a marina. After all, this is what electric cars are doing and still claim to abide by the zero emission principle.

It could be an acceptable solution for anyone planning to have an electric boat where access to charging points is easily available such as the Mediterranean, the Baltic, the Great Lakes, or coastal cruising generally.

On our return to the boatyard improvements to the regenerating system were implemented. Having two ServoProps doubled the previous regeneration capacity. This was proved during a three-day offshore test sail that showed Aventura Zero was now capable of covering all its electricity needs by regeneration.

Based on that experience, I can say the aim of zero carbon footprint on a sailing boat is certainly achievable. The future is indeed electric!

Next month: Jimmy will describe the many special features used on his boats, which have contributed to making his voyages both safe and enjoyable.

Why not subscribe today?

This feature appeared in the April 2023 edition of Practical Boat Owner. For more articles like this, including DIY, money-saving advice, great boat projects, expert tips and ways to improve your boat’s performance, take out a magazine subscription to Britain’s best-selling boating magazine.

Subscribe, or make a gift for someone else, and you’ll always save at least 30% compared to newsstand prices.

See the latest PBO subscription deals on magazinesdirect.com