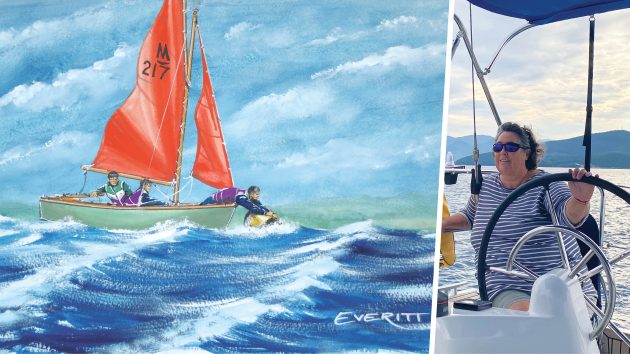

A heavily pregnant Kerry Buchanan tries to stem the water ingress in a 11ft 6in plywood dinghy off the coast of Donegal in the northwest of Ireland…

Fraser and I have almost sunk several times in all the years we’ve sailed together. Once was when we unknowingly towed a lobster pot on our prop shaft from Coleraine to Rathlin Island, resulting in damage to a shaft seal that caused massive water ingress while the engine was in gear.

Another time was when we had a leak in the rudder stock as we sailed down to Dublin from Bangor. But the most dramatic occasion was the time we thought we’d holed our 11ft 6in plywood dinghy off the coast of Donegal.

Fraser had built the dinghy from plans in our tiny garage near Oxford, about as far from the sea as you can get. She was of stitch-and-tape design, and very robust.

We trailed that little dinghy, with her brave British racing green hull, all over the place. On this occasion, we brought her on holiday to Donegal with us.

Bunagee is a lovely little fishing harbour on the Inishowen Peninsula, not far south of Malin Head, Ireland’s most northerly point. The weather can be beautiful, but it’s better known for its soft and persistent drizzle and its storms.

Article continues below…

Learning from experience: Chasing the leak on a sinking boat in Lyme Bay

Dr Brian Johnson became quickly and intimately acquainted with his engine’s silencer when it threatened to sink his Westerly Pageant…

Mud team to the rescue! Lessons learned from running aground on a sandbank

Paul Simon used to sing to me that ‘the nearer your destination, the more you’re slip-slidin’ away’. I never knew…

Open water

We launched Drhumbeat (so called because the plans were for a Rhum dinghy designed by Selway Fisher) at the slipway, beneath the severe glowers of the local fishermen. As they muttered and glanced at us in our shorts and neon buoyancy aids, I was sure I could hear them passing judgement on the mad tourists.

Fraser’s brother, Neil, decided to accompany us. He’s not a sailor, and he has quite a cautious personality, which makes me wonder why he chose to come with us. We didn’t bother with the outboard, because the wind was perfect and we saw no need for a noisy, smelly petrol engine. Besides, we had oars, didn’t we?

At seven months pregnant with our second child, I would have found it hard to duck beneath the boom or change sides as we tacked, so I took up position on the bottom boards, legs either side of the centreboard casing. I wasn’t sure how I’d ever get out again, but that was a problem for later.

Launch point – Bunagee Pier at Culdaff in County Donegal, Ireland. Photo: George Sweeney/Alamy

The little boat flew across the waves, wind singing through her lightweight Mirror dinghy rig, and she performed beautifully as always. Even Neil, not really a sailor, almost smiled.

But of course we became over-confident. Before we knew it, we were out beyond the arms of Culdaff Bay, and we quickly realised how very different the weather was in the open sea.

The swell pushed us around and the little dinghy heeled, lifting her skirts to race across the breaking waves. We yahooed and squealed with delight. This was what sailing was all about. Still, time to turn for home before we went any further out. Fraser brought Drhumbeat about and pointed us back towards the tiny harbour.

A Rhum 11 Mk1 dinghy in action. Photo: selway-fisher.com/Marc Fleischmann

Worrying noise

At first, all went well, but then a loud crack came from the bottom of the boat and her motion changed abruptly. Neil thought (bless him) that my fat backside had gone through the bottom of the boat.

We shoved aside lines and balers to search for water ingress. I shifted my bum aside, expecting to see splintered plywood. Nothing. The boat was still dry.

Then Fraser pointed behind us. The centreboard had snapped off flush with the bottom of the housing and was bobbing on the surface a few boat lengths behind us.

Family friend Benedict Reney with Drhumbeat

Now, the Rhum dinghy is a beautiful design, but she is hard chined, and has a fairly flat bottom. There’s little but the centreboard to prevent her sailing as fast sideways as she does forwards.

We were faced with the prospect of steering a boat with about 60-70° of leeway back into a narrow harbour entrance and onto a trailer.

Once back inside the bay, we managed to grab hold of a mooring buoy to give us time to think. Neil wrapped his arms around it like a drowning man. That’s when we realised how strong the tidal flow was. It took all his strength to hang on.

Communications void

We discussed our options. We had no VHF radio or mobile phone, because we were only sailing inside the bay, well within sight of family ashore.

The family had disappeared back into the cottage and were probably watching us through binoculars while they munched on treacle scones and sipped mugs of tea. The fishermen paid us no attention at all.

If you’ve watched the Pirates of the Caribbean films, you might remember a moment when Captain Jack Sparrow orders the crew to head for: “Land, any land.” This was one of those moments.

Bunagee Harbour in North Donegal, and the wide expanse of beach Kerry, Fraser and Neil were aiming for. Photo: Thomas Lukassek/Alamy

Luckily, Culdaff Bay boasts a long crescent of golden sand with rocks at either end but few nasty surprises in the entire middle section. We pointed her bow at the rocky northern end and hoped our leeway would allow us to hit the beach and not the southern rocks.

We made it, just. Drhumbeat surfed onto the beach and up the sand like a World War II landing craft. We all staggered ashore, legs perhaps a little shaky but flooded with adrenaline.

I needed both Fraser and Neil’s help to lever me out from my wedged-in position. “I’m never, ever getting in a boat with you two again,” Neil said. “You’re a pair of lunatics.”

A Rhum dinghy similar to Drhumbeat. Great little trailer-sailing boats and surprisingly nippy. Photo: selway-fisher.com/Marc Fleischmann

“So, you’re not going to help us motor her back to the harbour then?” I asked. He eyed the crashing surf. “I’ll help carry the outboard down here for you, but then you’re on your own.”

With the outboard in place and the rig dismantled, Fraser and I relaunched her. I got in first, producing my stranded walrus routine, and Fraser pushed us off, leaping in as the first breaking waves hit us.

The surf had built up quite a bit in the time it had taken to fetch the outboard, and the brave little boat reared up with every wave, threatening to go over but somehow managing to stay upright.

We got her safely back to Bunagee Harbour, retrieved her onto the trailer, and lived to sail many other days. Oddly enough, the baby who accompanied us as a bump turned out to be the only one of our three children who gets seasick. No idea why.

Lessons learned

- I shouldn’t be recommending sailing a small dinghy while heavily pregnant… so I won’t.

- Novice sailors often underestimate the conditions a little further out. We certainly did.

- These days, we tend to take a walk along the coast for a bit to check what it looks like. If there are white horses, we walk back to the boat and put the kettle on.

- I was surprised at just how much leeway that little boat made without her centreboard. I’m not exaggerating how difficult it was to aim for even a beach as long as Culdaff (nearly a kilometre of sand) and we only just made it.

- Fraser says he designed the centreboard as a weak point in case of the boat being over-pressed, so he wasn’t that surprised when it snapped under pressure.

- It’s nothing short of stupid to sail any boat without a reliable means of communication. We should have brought at least a handheld VHF with us, and we definitely learned a lesson from that day’s experience.

- Don’t rely on being rescued. The fishermen were almost certainly aware we were in mild difficulty, but our family ashore had no idea until they realised we weren’t returning to the harbour. Even then, they didn’t know what the problem was.

- If building a dinghy, be very careful where you source your plywood as it varies in quality and brittleness. Fraser should know, as he’s a materials engineer!

Expert advice from the RYA

Expert advice from the RYA

Royal Yachting Association (RYA) cruising manager Stuart Carruthers said: “Without wishing to sound patronising, Kerry has learned the importance of having a means of keeping in touch, but an element of planning is required for even the simplest and shortest of journeys.

“When you are keen to get going it can seem like a chore to plan, but it will help you to consider your options and ‘what-ifs’. It needn’t be complicated; think about what might happen should things change.

“This will help you to decide whether you are properly prepared so your trip goes without a hitch and enables you to enjoy your day.

“Above all, when things go wrong – and they do – then it’s vital you have a suitable means of communication for routine messaging and emergency situations.

“Most people these days have a smartphone even if they do not have a handheld VHF, and for situations such as these it is worth downloading the RYA SafeTrx App.

“This will help you keep in touch with friends and family and if things go really wrong, the App has an alert and track feature, which when activated, transmits your position regularly to the Coastguard helping them to provide assistance quickly.

“It is free to download and to use – it could save your life – and a waterproof pouch to keep you phone in costs peanuts!”

The RYA publishes a wide range of guidance and safety advice online.

Do you have a boating experience story? Send it to pbo@futurenet.com and if it’s published you’ll receive the original Dick Everitt-signed watercolour which is printed with the article.

Why not subscribe today?

This feature appeared in the May 2023 edition of Practical Boat Owner. For more articles like this, including DIY, money-saving advice, great boat projects, expert tips and ways to improve your boat’s performance, take out a magazine subscription to Britain’s best-selling boating magazine.

Subscribe, or make a gift for someone else, and you’ll always save at least 30% compared to newsstand prices.

See the latest PBO subscription deals on magazinesdirect.com