Jimmy Cornell boils down decades’ worth of world cruising surveys to find the five factors that affect voyage success…

For 35 years I have been keeping a record of the global movement of sailing yachts by obtaining the number of arrivals in several key locations around the world.

During this period there has been a steady increase in those numbers; the most significant being the number of transits by cruising yachts through the Panama Canal, which went up from 495 in 1987 to 919 in 2022.

Las Palmas de Gran Canaria is the foremost sailing hub in the North Atlantic where yacht arrivals rose from 1,038 to 1,237. At Horta in the Azores, there has been a near two-fold increase from 614 to 1,131. Arrivals in New Zealand grew from 250 to 489 while Tahiti saw an increase from 328 to 404.

High latitude destinations have also seen a marked increase from only four yachts calling at Spitsbergen in 1990 compared to 52 last year, with an increase in Antarctica from eight to 26 over the same period.

The only place where there was drastic reduction was the Suez Canal, which recorded a fall from 198 in 2000 to 36 in 2022. This is undoubtedly due to safety concerns, with sailors preferring the safer route around the Cape of Good Hope as shown by the numbers going up in Cape Town from 67 to 126.

Article continues below…

Jimmy Cornell boat survey reveals how much sailing has changed in 40 years

‘During the past four years I have sailed through some of the major crossroads of the cruising world: Rhodes, Gibraltar,…

Offshore sailing gear: How to prepare a boat for extended cruising

Sea Bear is a Vancouver 28 built in 1987. She was generally in very good condition when I bought her,…

On a global level, an estimated 10,000 boats are undertaking a long voyage at any given moment. The vast majority have a happy ending. That was certainly the case with my own voyages and also for the majority of participants who sailed in my rallies, whether transatlantic or around the world.

Bearing in mind the many challenges that those sailors had to overcome to bring their voyages to a successful conclusion, it’s remarkable how relatively small the number of failures was.

From the cases of unhappy or abandoned voyages that have come to my knowledge over the years, and from conversations with owners and crews, I have narrowed down the most common factors that can contribute to the success or failure of a voyage.

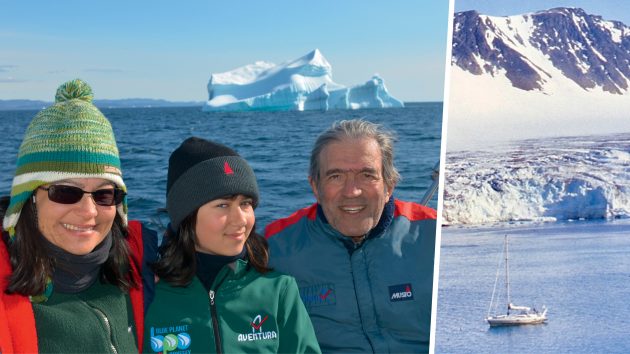

Aventura IV, Garcia Exploration 45, a boat for all seas and all seasons, Jimmy Cornell’s yacht

These are the boat itself, inadequate funds, the inability to be self-sufficient, problems with the crew, unforeseen circumstances, and a wrong attitude to cruising and life at sea generally.

These are such important matters for anyone planning a long voyage that, over the years, I conducted surveys among long-distance sailors, as well as participants in my sailing rallies, to find out more about those causes.

1. The right boat

What kind of boat to acquire for a long voyage is often a more difficult decision than deciding to do the voyage itself, especially when there is such a wide range available. The wrong choice will undoubtedly seriously affect the quality and enjoyment of a voyage and may lead to the voyage being curtailed and even abandoned.

Jimmy Cornell with son Ivan and daughter Doina on his catamaran Aventura Zero

There are many factors that can make a boat unsuitable for a long voyage, and the most common is the wrong size – either too large to be handled easily by a short-handed crew, or too small to be comfortable, having limited storage capacity or being slow on long passages.

The fact that too large a size might be a handicap, especially if the crew are not experienced, was evident on several boats over 50ft sailed by a couple alone. Finding it difficult to handle the boat on their own, many were forced to take on extra crew, a solution that in many cases proved to be just as disadvantageous.

As one of them advised: ‘Don’t go for a bigger boat than you need just because you can afford it.’

Health and general fitness are important – handling a boat can be very physical. Photo: Steve Hawkins Photography/Alamy

Comfort is a major factor and has a bearing not only on the wellbeing of the crew, but also on safety. And, indeed, safety is the most essential consideration when choosing a boat for a long voyage. There are many vessels that are perfectly suitable for weekend sailing or short cruises but which may not be up to the demands of tough offshore conditions.

Participants in the voyage planning survey were asked to name the most important features that contribute to the quality and enjoyment of a voyage. Regardless of size, one of the most desired features mentioned was a comfortable, sheltered watch-keeping position and an ergonomically-designed cockpit, if possible with a hard dodger, which makes passages more comfortable in both hot and cold climates.

Another desirable feature was a shallow draught, because it extends the cruising range, whether a catamaran or a centreboard monohull. Other features mentioned were good access to the engine room for maintenance, a compact user-friendly galley, comfortable sea berths and a double berth for when in port.

Too large a boat size might be a handicap, especially if the crew are not experienced

As to sail handling, a well thought-out reefing system was considered essential, with the lines being led to the cockpit, ideally to an electric winch. Plus easy access to the chain locker, with a vertical drop to avoid the chain getting snagged, and serviced by a powerful, reliable windlass.

As most of those interviewed had spent long periods sailing in tradewind conditions, several mentioned easily handled downwind sails, such as a cruising chute or spinnaker.

The four most commonly mentioned pieces of essential equipment were a powerful autopilot, a reliable watermaker, Automatic Identification System (AIS) and bow-thruster. For communications, access to weather forecasts topped the list while underway, followed by an efficient email setup, and a satellite phone.

Survey participants were asked to give practical advice to would-be voyagers. Many pointed out that those with limited offshore experience might be unaware of the high electricity demands of a boat equipped for a long voyage and should ensure their demands would be met, preferably by renewable sources.

Aboard Aventura Zero – Jimmy recommends thorough briefings for new crew

2. The right crew

The owner of a boat that had sailed both in the Atlantic Rally for Cruisers (ARC) and a round the world rally, and who’d had more than his fair share of crew problems in his long sailing life, was of the firm opinion that ‘nothing can spoil the pleasure of a voyage more than problems with your crew’.

His comments echoed my own feelings, as I believe that more voyages have been abandoned because of crew problems than by the wrong choice of boat, gear failure or financial concerns. This conclusion is based in part on my personal experience, but it is mostly drawn from countless examples that I have come across as the organiser of cruising rallies.

Even allowing for the fact that I was dealing with very large numbers of people, the proportion of boats that experienced crew problems was much higher than I would have expected.

By the time Jimmy’s Aventura III yacht came along his wife, Gwenda, only wished to join the cruising stages, not long passages, so Jimmy began to factor in crew

This may explain why the majority of boats on a long voyage are sailed by couples, and completed successfully, which is not the case on some of the boats crewed by friends, acquaintances or occasional crew taken to supplement the permanent crew.

My advice to anyone planning to take on crew, even for just one ocean passage, is to take into account not only their experience, but also their physical condition, reliability, and their compatibility with other crew members.

Physical sport

Health and general fitness should be given a high priority as part of the preparations for a voyage, whatever the age of the crew – and many long distance sailors are no longer in their prime.

This is especially true when sailing offshore where medical assistance will not be easily available. After a long period of urban, sedentary existence, it’s essential to get into good physical shape for the impending voyage.

Many people do not realise just how important physical fitness is on a boat. As a highly experienced skipper pointed out: ‘You must prepare yourself physically but also mentally for what can be a demanding way of life.’

‘A boat is not a place to fix a relationship. If someone irritates you ashore, they’ll irritate you more on a boat’

More than half the boats in a survey on voyage planning were crewed by couples on their own, with only a few who occasionally took on additional crew.

Among the former, several stressed that they preferred this arrangement, with one explaining: ‘The advantages of doing long passages as a couple are huge, provided both are fully competent. You only need one decent sea berth, watch-keeping routines are easy and you haven’t got the responsibility towards other crew. Less is more. The more people in a small space, the more potential for problems.

‘Modern technologies such as autopilot, windvane, radar and AIS have made it much easier to sail short-handed. Although for watch-keeping we would prefer to have at least one extra crew member aboard, the logistics of doing so, and the limited space available, convinced us that just the two of us was a better choice.’

Concerning boats crewed by just a couple, a vital point raised in the survey was to ensure that in an emergency the other person is able to deal with any essential tasks.

Jimmy’s surveys found that sailors who successfully completed long voyages shared traits of courage, perseverance, determination and self-confidence

Crew clash

I must admit that for many years I believed that bad experiences with crew only happened on other boats, but I was proven wrong after I stopped sailing with family members or old friends and occasionally had to take on crew for some long passages.

Some incidents were not serious and could easily be ignored, but when it came to unpleasant personality clashes, I realised that I was just as vulnerable as everyone else.

On our six-year long voyage on the first Aventura, we sailed just the four of us virtually all the time with only a few exceptions when family members or close friends joined us for a few days. The happy atmosphere on board set the tone for me and made me believe that this was normal.

It did indeed continue on Aventura II, but Aventura III’s meandering voyage confronted me with the same painful dilemma faced by many sailors whose partner was no longer in tune with his expectations.

After several months of sailing with me all the way across the South Pacific from the Marquesas to New Zealand, Gwenda told me that she was no longer keen on long ocean passages, and made it very clear why.

‘Setting off for a life on the ocean entails a complete change of both lifestyle and mentality’

“I think it is important to know your interests and limitations, and in my case, I have reached the point where I no longer enjoy it. Of course, I can do it if necessary because I’ve done it before, but if you don’t enjoy something you are just a dead weight on the others.”

From New Zealand onwards, Gwenda only joined me for some cruising stages, but no long passages, so I had to continue the voyage with various crew, usually one or two. By the time I completed the voyage two years later, a total of 12 different crews had sailed with me. I’m happy to say that with one exception it all worked out well.

The main reasons were threefold: I chose my crew carefully, briefed them extensively beforehand on what to expect, and – probably most important – I had the experience not just how to deal with my crew, but to show them by example that I knew all there was to know about my boat and sailing it.

Tensions on board

Unfortunately, I had a very different experience on Aventura IV’s voyage, possibly explained by the tensions caused by a challenging Arctic expedition.

As half the crew on my first attempt to transit the Northwest Passage were family members – my daughter Doina, granddaughter Nera and niece Marianne – I attempted to maintain a relaxed and happy atmosphere on board, being more tolerant of mistakes than I should have been.

This was interpreted by some of the other crew as a sign of weakness, and their condescending and disrespectful manner became hard to bear. In hindsight, that unhappy situation had some bearing on the decision to abandon that first attempt.

On my second attempt, I was determined to avoid making the same mistake, and was quite firm in my dealings with the crew. I tried to set the scene from the very beginning by stressing the fact that we were setting off on an expedition and that, in order to bring the voyage to a successful end, we needed to be disciplined and committed.

We did complete the transit of the Northwest Passage, but the atmosphere on board was often tense. Regardless of my feelings at the time, I’m grateful to my crew for their role in making it happen.

Those experiences have taught me some valuable lessons about human nature. They also reminded me of the bitter comments made by a sailor who’d moved up from his smaller boat, which he had sailed with his wife in the first round the world rally, to a much larger yacht.

Being forced to use a professional captain and crew, he attempted, just like myself, to maintain the easy-going atmosphere as on his previous boat. ‘It simply didn’t work, and the answer is very simple: you cannot be loved and respected at the same time.’

3. Healthy finances

No voyage should be embarked on without recourse to adequate funds, not just for day-to-day expenses, but also as a reserve for possible emergencies. The situation is now very different from the days when it was still possible to sail the world on a limited budget.

Life on a floating home has become more expensive due to several factors: the high cost of insurance, the rising price of marina and boatyard fees, formalities and cruising permits.

Financial matters were an important part of my ongoing voyage planning surveys, and their findings were updated recently. The average annual expenses quoted by couples sailing on boats between 40-45ft varied between £20,000 and £30,000. For couples on boats between 50-55ft, the annual costs generally spanned £35,000 to £50,000.

To update those figures for this report I contacted 10 participants in the latest voyage planning survey, currently cruising in various parts of the world, from New Zealand to the Tuamotus, Sicily to the Caribbean.

I asked them to send me an estimate of their annual expenditure. With two exceptions, all got back with precise figures, which varied widely, from £12,000 to £50,000, and largely confirmed the above findings.

The person with the lowest budget, a retired Brazilian airline pilot on his second circumnavigation, pointed out that to save money, ‘I do all the maintenance and repairs on the boat myself. We avoid marinas as much as possible. Also having meals ashore to maybe once every 10 days.’

A Danish engineer in early retirement, sent me a breakdown of all expenses on a two-year family voyage that included the Mediterranean, Canaries, Caribbean and the Baltic.

‘The Balearics were the most expensive of the entire itinerary and, to our surprise, the Caribbean was the cheapest, mostly because there are fewer marinas, plenty of wind to sail with no need to spend money on fuel, and the drinks are cheap.’

His monthly averages were: £3,600 in the Mediterranean, £2,300 in the Canaries, £1,400 in the Caribbean, and £2,600 in the Baltic.

A Hungarian family on an open-ended world voyage with their two young daughters wrote: ‘French Polynesia, where we are now, is very expensive. We spend around £2,000 to £2,400 per month, which includes everything except large, unexpected boat repair or equipment replacement bills.’

At the other extreme, an Australian couple on a world voyage on a larger boat wrote that: ‘Our annual budget is between £45,000 to £50,000. Those figures are all inclusive.

‘We estimate that 40% are boat related expenses, such as fuel, maintenance, repairs, replacements and insurance. The remaining 60% represent living expenses and include a return trip home every year.’

Broken dreams

Main causes that have led to the curtailment or abandonment of a voyage…

- Wrong choice of boat: – Too large and difficult to handle by a short-handed crew (usually just a couple). – Not well prepared and equipped for a long voyage.

- Lack of essential spares; inability to deal with even simple repairs.

- Inadequate autopilot and no backup (spare autopilot or wind self-steering gear).

- Tension between owner and crew.

- Crew incompatibility.

- Safety concerns in places along the planned route.

- Health issues.

- Financial issues.

Jimmy Cornell reading – Happiness on passage

4. Self-sufficiency

The ability to be self-sufficient has been lost by many people in today’s world when help is often just a phone call away. Not only the skills required but also the attitude to try to deal with a problem before calling on outside assistance.

Many of those interviewed stressed that this apathetic approach is of not much use on a boat in the middle of the ocean, where you must be able to deal with any emergency yourself.

Many skills are needed on an offshore voyage, such as the ability to repair and improvise, navigate without electronic aids, dive, give first aid, or sail the boat if the engine is out of order.

The boat should carry a comprehensive set of tools, essential spares and backups for the most important pieces of equipment. There should also be a well-stocked medical chest and at least a basic knowledge of how to deal with a medical emergency.

I learnt the importance of being self-sufficient early in my sailing life and, having fitted out the first Aventura myself, I not only knew the boat well but also had the skills and tools to deal with emergencies. On all my subsequent boats I had a full set of tools and essential spares to sort out every crisis that I was confronted with.

The significance of being self-sufficient was put to the test during the Covid pandemic when authorities in practically every country on the popular cruising routes closed their borders to new arrivals. This unexpected situation caused havoc among the many sailors undertaking a longer voyage.

As many popular cruising destinations closed their borders, those who were caught out had to either postpone their plans or leave their boats unattended and return home. In some places, those who were allowed to stay had to remain at anchor, were forbidden to go ashore and had difficulties getting provisions, fuel or even medical attention.

The unforeseen circumstances caused by the prolonged interruption of their voyage resulted in several cases of the abandonment of the planned voyage.

Many skills are needed on an offshore voyage, such as the ability to repair and improvise

Adapting to change

In recent times there have been other circumstances where sailors were forced to change plans, such as during the piracy crisis in the North Indian Ocean when some voyages had to be changed from the Red Sea to the Cape of Good Hope route.

While the risk of piracy has abated, the current uncertain situation in the Red Sea continues to make the latter route the safer choice.

The impact of climate change is the latest factor to affect voyage planning. This significant phenomenon was the subject of my latest survey. The 65 sailors were asked how their own decision would be affected were they to plan a world voyage now.

Without exception, everyone pointed out that while they were aware of the consequences of climate change, they would take that factor into account but would still be prepared to embark on a long voyage.

All agreed that proper voyage planning was now even more important than in the past. Indeed, by being aware of the consequences of climate change, with careful planning tropical storm seasons and critical areas can still be avoided.

Bearing in mind the changed circumstances, these are the basic safety measures that should be adhered to when planning a voyage now or in the near future:

- Arriving in the tropics too close to the start of the cyclone-free season should be avoided, and a safe margin should be allowed by leaving a critical area before the end of the safe period.

- Cruising during the critical period in an area affected by tropical storms should be avoided. Those who plan to do so should monitor the weather carefully and make sure to be close to a place where shelter could be sought in an emergency.

- Those who leave the boat unattended should make sure that their insurance company agrees with those plans.

What stands out from my exchanges with such a variety of sailors is their positive, optimistic attitude. Even the person who expressed some doubts about climate change wanted it to be known that whatever might be coming, ‘Even a bad day at sea is better than a good day in the office.’

`Jobs such as servicing winches is all part of the success of long-haul voyages. Photo: Mike Robinson/Alamy

5. The right attitude

A boat that incorporates one’s main priorities is absolutely crucial for the successful outcome of a voyage, but other factors can have a serious effect on its success, and they are, as mentioned before, crew, finances and self-sufficiency.

There is, however, an even more important factor that can have a bearing on the success of a voyage, and that is your attitude to the sea and sailing, and to cruising life in general.

Setting off for a life on the ocean is a major decision that entails a complete change of both lifestyle and mentality, something that some people may not have considered carefully. Leaving on a voyage in a sailing yacht just because it is a convenient way to see the world is not a good enough reason.

I’ve come across this attitude among sailors I’ve met, some of whom were unwilling, or more often unable, to make the transition from a shore-based person to full time sailor.

This may not be a great problem on a relatively short voyage, such as sailing to the Caribbean and back, but it can have serious consequences for those who leave on a longer journey of several years. In the final analysis, the ultimate success of a voyage does not depend on the boat, but on you and your attitude.

A participant in the latest survey highlighted the crucial importance of one’s mindset to the successful outcome of a voyage: ‘A boat is not the place to fix anything wrong with a relationship, whether it is with a partner, a child or a friend.

‘If someone irritates you ashore, they will irritate you more on a boat. Some people are not emotionally geared for life aboard. They are not wrong or misfits, they are just not boat people.’

In my 50 years of sailing I have met many outstanding people and, invariably, what made them stand out was their attitude. What I most admired in them was their profound respect for the sea, and how being on the ocean came to them naturally, undoubtedly because they loved what they were doing.

Some I met while cruising, others as participants in the various sailing events that I organised, and over the years several have become close friends. What they all had in common was that vital frame of mind to embark on a long voyage, which required such qualities as courage, perseverance, determination and self-confidence.

The fact that we live in an age when it is so much easier and safer to sail to the remotest parts of the world has not changed those requirements in any way. The safety situation in certain parts of the world may cause concern, as do the effects of climate change. But there are still plenty of peaceful places to explore and exotic destinations to enjoy.

All that is needed is a positive attitude. In the final analysis, how satisfying and enjoyable your life on the ocean will be is not determined by how big or small, how comfortable or well equipped your boat may be, nor by how much money you have, but primarily by your own attitude.

Alone on a small boat in the middle of an ocean, far from land and outside help, a captain has their own destiny, and that of their crew, in their hands. Nothing can describe this situation better than the words of the poet WE Henley:

It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll,

I am the master of my fate:

I am the captain of my soul.

Why not subscribe today?

This feature appeared in the September 2023 edition of Practical Boat Owner. For more articles like this, including DIY, money-saving advice, great boat projects, expert tips and ways to improve your boat’s performance, take out a magazine subscription to Britain’s best-selling boating magazine.

Subscribe, or make a gift for someone else, and you’ll always save at least 30% compared to newsstand prices.

See the latest PBO subscription deals on magazinesdirect.com