A wonder material in the 1950s and 1960s, plywood played a big part in making boating accessible – and today it’s making a comeback. Rupert Holmes analyses what lies behind a new wave of ply boats

Seeing the materials that go into the hull of a 40ft yacht flat-packed and stacked on a single large pallet is an arresting sight. Yet that’s exactly what happens at RM Yachts in La Rochelle, a well-known French boatbuilder that has been constructing state-of-the-art plywood boats for more than 30 years.

Why build plywood boats these days?

“It’s very lightweight but also very stiff, which is good for performance and for sailing qualities,” RM’s Léa Laurent told me when I visited the factory during the La Rochelle boat show.

“It’s also a flexible, artisanal kind of production and more environmentally friendly than fibreglass.”

Laurent says almost all RM clients understand the advantages of the construction method “before they come to us.”

RM Yachts uses plywood because it is lightweight and stiff and more environmentally friendly than fibreglass. Credit: Rupert Holmes

However, that’s not always the case in the wider boat-owning community, perhaps because the huge benefits of epoxy coatings and sheathing in extending the longevity of the structure are not fully appreciated.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, a plywood boat was more likely to be regarded as a liability that required lots of maintenance to prevent what was seen as the inevitability of rot developing.

But even then that was not an entirely accurate perception, providing the water could be kept out of the timber.

Prompt attention to any chips or cracks in the paintwork was therefore essential, but didn’t need to be unduly time-consuming.

The golden age

Economy was a key driver of the 1950s and 1960s boom in plywood boatbuilding, including the 17ft Lysander and Silhouette, 18ft 6in Caprice, 24ft and 26ft Eventides and scores of other small cruising boat designs, dinghies and small racing keelboats.

Quite simply this was a far cheaper material than more conventional planked timber construction.

As a result, this is the attribute we tend to immediately associate with plywood.

However, even back then the advantages of plywood construction, particularly its strength-to-weight ratio, were well-known and exploited for cutting-edge designs.

There are plenty of high-profile plywood boats still in operation, from a myriad of racing dinghies to large yachts.

Stormvogel was one of the stand out large yachts of her generation and proved that laminated timber was suitable for world class racing yachts. Credit: Rolex/Kurt Arrigo

Dutch timber magnate Cornelius Bruynzeel, who’d won the 1937 Fastnet Race, was an early advocate of the material and had already enjoyed considerable success, including a class win in the Fastnet with the 40ft Zeevalk, which was built of plywood in 1949.

For his next boat he wanted a much larger vessel, the result was the 74ft Stormvogel of 1961.

Designed by EG Van de Stadt, with assistance from British naval architects Laurent Giles and Illingworth & Primrose, and built in South Africa, this was one of the most advanced yachts of her era, with a low centre of gravity bulbed fin keel and separate skeg hung rudder.

To achieve a round bilge shape she was built over fore and aft stringers from four layers of Khaya mahogany, stuck together with Resorcinol glue.

Bruynzeel sailed her to regattas across the globe, and Stormvogel remains an outstanding example of a high-tech lightweight yet very strong yacht.

For example, she took line honours in the 1961 Fastnet Race and six decades later scored seventh and 11th places overall respectively in the unusually windy 2021 and 2023 editions.

In 1953, Robert Tucker’s 17ft Silhouette could be built for £100. There are still many examples sailing. Credit: Rosie’s Ice Cream Shoppe

At the other end of the size spectrum, Silhouette Owners’ International Association rallies also always feature a host of immaculately maintained examples of this twin-keel Robert Tucker design, originally from 1953.

Back then the materials cost only £100 and many of the early boats were by DIY builders.

The design remained in production for more than two decades, albeit with a great many modifications.

Mark 2 models from as early as 1962, as well as the later Mk3, 4 and 5 versions, were built of fibreglass and in total several thousand were built.

Dry as a bone

Nevertheless, before the widespread use of epoxies from the late 1970s and 1980s onwards, if water was allowed to penetrate the timber for a lengthy period the results could be devastating.

On the plus side, plywood is an easy material to work with – replacing the foredeck and transom on the 20-odd-year-old 18ft Caprice I bought as a sixth former, for instance, was not a difficult task and gave the boat a new lease of life.

For more than 30 years it has now been standard practice to sheath plywood hulls and decks with epoxy and glass, which provides excellent protection, including impact resistance.

Continues below…

How to build a boat: Essential guide to building your first kit boat

You don’t have to be a boatbuilder to learn how to build a boat, argue Roger Nadin and Polly Robinson.…

RM890: ‘Fast, fun and functional’

If you want an easy-to-handle performance cruiser that stands out from the crowd, have a look at the RM890, suggests…

Best sealant kit to keep on board your boat

Sealing screwed-on windows: With screwed in windows the purpose of the sealant is to keep water out, not to glue…

Sailing the 3.3m Jack de Crow from the Black Sea to Venice

Sandy Mackinnon sailed the 10.8ft Jack de Crow across the Black Sea and the Mediterranean Sea to fullfil his dream…

Therefore touching up paint chips to keep the water out is a thing of the past.

Of course, if the epoxy/glass is punctured – which requires a far heavier impact than paint applied directly to timber – this does need prompt attention but can be covered with waterproof, UV-resistant tape, or a smear of epoxy (even Araldite will work) as a quick temporary measure.

The extremely sticky nature of boatbuilding epoxies means this outer sheathing is far more effective at protecting the structure than early plywood boats that were covered in fibreglass using polyester resins.

These often eventually became detached from the substrate, allowing moisture to infiltrate between the timber and the outer skin, where the presence of the sheathing meant it would never dry out.

Boats sheathed in Cascover from new tended to fare better in this respect, even though it was not as good as epoxy, but this significantly increased costs so few boats gained the benefit of Cascover.

Returning to plywood

Today RM is by no means alone in building plywood boats – the material has been adopted by a growing number of smaller, innovative boatbuilders, particularly in the mid to high end of the market, both for racing and cruising.

The well-known UK boatbuilder Swallow Yachts, for instance, has been building a 30ft motor cruiser, the Whisper 300, using plywood clinker construction for the past few years.

This is a strong but lightweight vessel with accommodation for up to four people, yet twin 70hp outboard engines provide enough power for a top speed of 26 knots.

That represents a huge up-front saving compared to fitting larger engines, while simultaneously slicing a large chunk off running costs compared to the twin 200hp engines of many similar-sized motor boats.

The Swallow Yachts’ Whisper 300 – a 30ft clinker plywood/epoxy motor boat that can achieve 26 knots powered by just two 70hp outboards. Credit: Swallow Yachts

Swallow Yachts’ managing director Matt Newland tells me the Whisper 300 demonstrated this method of boatbuilding is as cost-effective for them as conventional fibreglass construction.

Swallow’s next model, the BayCruiser 32, a lightweight 32ft trailer sailer, will employ the same concept.

This will combine both traditional and cutting-edge elements, including water ballast and carbon spars, to create a boat that weighs only 2,300kg, making it one of the few of its size that can be towed to a different location for a summer cruise.

Even after fibreglass became popular it was well recognised in many competitive dinghy racing fleets that the plywood boats were stiffer than their fibreglass equivalents and retained that stiffness in the longer term.

It was not until foam sandwich fibreglass construction became well established that it could equal humble plywood.

Material of choice

Today, in the racing world, plywood’s inherent stiffness and light weight make it ideal for building one-off race boats and small production runs without a mould.

Increasingly, carbon reinforcement, particularly around the chainplates and the keel area, is used for additional local reinforcement, without having to resort to the use of thicker ply which carries a weight penalty.

The Ace 30 radical scow bow IRC racer, for instance, uses mostly 12mm okoume ply for the hull, although 15mm is used for some parts of the structure.

Outside of this are two layers of biaxial rovings, plus a third at 45°.

Plywood is the material of choice for those building Wharram catamarans. More than 10,000 sets of Wharram plans have been sold. Credit: David Harding

These are laid up using bio-resins and increase strength, particularly around the keel, where the lay-up is thicker, while also providing impact resistance to protect the timber.

Inside the boat, the ply is coated and impregnated with epoxy but is not sheathed with glass.

Antoine Mainfray, founder of the Ace 30 builder, La Rochelle-based Atlelier Interface, and the boat’s designer, told me the use of plywood for this model is a key factor in reducing the total carbon emissions relating to the build to only 1.9 tonnes.

That’s less than one-third the figure for a similar vessel of conventional fibreglass construction.

Equally, plywood has always been the material of choice for Wharram catamarans, for which more than 10,000 sets of plans have been sold over the past 50 years.

They made the transition to epoxy in the 1980s, which has helped to maintain the longevity and value of boats as they age.

Supreme protection

Sadly, many old plywood boats built before epoxy resins had been adapted for boatbuilding have succumbed to rot and disappeared after being broken up.

The edges of panels are particularly vulnerable to water ingress, especially on decks and coachroofs where rainwater can do far more damage than salt water, which has very mild preservative qualities.

The WEST system pioneered in the 1970s by the Gougeon Brothers in the USA utterly transformed the potential of wooden boatbuilding, but only came along after the demise of plywood as the most popular manufacturing method.

Nevertheless, owners of the smaller number of boats built since then have the reassurance that, if the outside is encased in layers of fibreglass and epoxy, this provides both impact resistance and waterproofing while several coats of epoxy will protect the inside of the boat.

These boats can last indefinitely provided the epoxy system is maintained in a good condition.

For anyone buying a contemporary timber/epoxy boat, a surveyor will be able to easily detect problems behind the sheathing through a combination of tap testing with a light hammer and a moisture meter of a type that measures water content below the surface.

On the downside epoxy can be relatively expensive both in terms of material and time, so today a new plywood boat is rarely a cheap option, but they have many other advantages, often including stunning aesthetics.

Other contemporary methods of building boats in wood

Strip planking

Modern strip-planked boats use timber – typically lightweight rot-resistant species such as cedar or Douglas fir – with a loose tongue and groove profile, allowing them to neatly conform to the hull shape and giving space for thickened epoxy glue.

They are typically built over laminated frames that become part of the final structure and therefore don’t require a mould that is subsequently discarded.

Spirit Yachts is one of the yards using strip planking to build their boats, like the Spirit 30. Credit: Waterline Media/Spirit Yachts

Often a couple of thinner outer layers of double-diagonal planking are added outside the strip planking, creating a monocoque structure that’s extremely stiff but lighter than conventional fibreglass construction.

Strip planking is therefore also ideal for one-off designs and short production runs.

The whole structure can then be sealed from water ingress and impact damage with epoxy.

Today Ipswich-based Spirit Yachts is probably the best-known yard building yachts in this manner, but there are many examples elsewhere.

Cold moulding

Here, strips of timber that are thin enough to bend easily are stapled to a mould that’s later discarded.

These can be built up in several layers, glued with epoxy and the staples removed, to create a stiff and strong monocoque structure that, like strip plank boats, can be protected with epoxy sheathing.

If clear resins are used for the latter the topsides can have a stunning varnished finish.

Note that in North America the term cold moulding tends to apply both to what’s called strip plank and to cold moulded construction in Britain.

RM Yachts: How plywood boats are built today

Today at RM all parts are cut off-site by a CNC machine and delivered well in advance of the start of construction so that they can settle to the temperature and the humidity of RM’s carefully controlled factory environment.

The company currently builds five models from 29-44ft, all of which have a permanently set up jig made of MDF or OSB that makes it easy to slot the plywood panels together.

Individual ply panels are connected fore and aft off the boat, using scarfs and big jigsaw-style joints to create a single giant full-length plank.

This makes for a smooth, seamless finish when applied to the jig and glued in place.

The joins between each section of ply are epoxy filled and taped over on both sides for additional reinforcement, then sanded and faired.

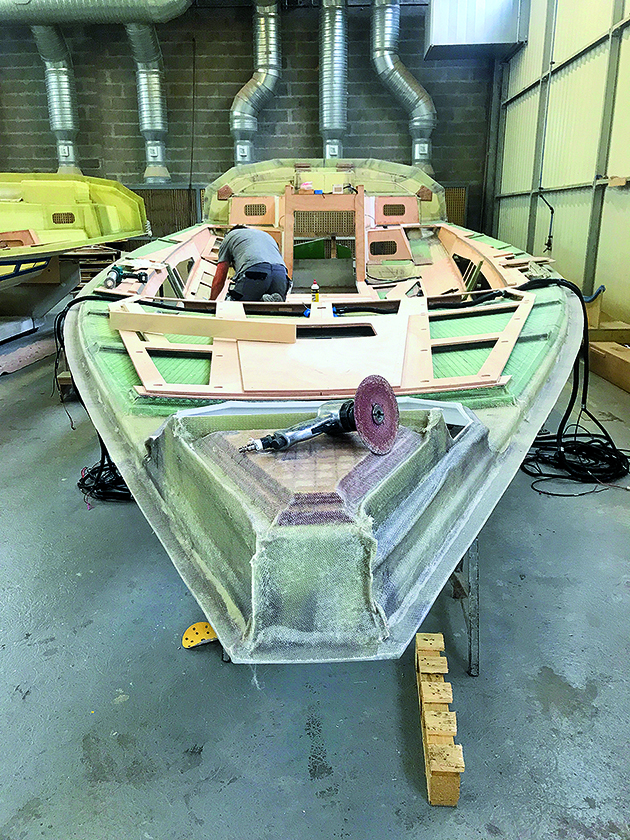

Once the main structural elements are complete, they can be lifted off the jig for further work, including bonding in bulkheads and adding the galvanised frames that distribute keel loads in both twin- and single-keel boats.

Eventually, both the inside and outside of the whole hull will be encased in layers of glasscloth and epoxy to give it impact resistance and waterproofing.

At this stage, the topsides are filled and faired but the final painting doesn’t take place until later.

Once the hull has been turned over it’s fitted out with tanks, machinery, wiring, plumbing and so on – it is much easier to do all those tasks before the deck is fitted.

Decks are built separately and in the case of RM are a composite of fibreglass and timber.

At an early stage, they’re fitted out with conduit, wiring, and deck fittings.

Once the deck has been bonded into place the final filling and fairing can take place, ahead of final painting.

The boat then gets its electronics, the final elements of the furniture, the rest of the deck gear and so on to produce the finished item.

RM’s site is sufficiently large enough to build up to 40 plywood boats a year, depending on the mix of sizes.

Plywood construction is particularly good for lower production volumes as the plugs and moulds required for conventional fibreglass boats represent a significant cost, material use and carbon emissions if they can’t be amortised across hundreds of boats.

Plywood boat build: step by step

Credit: Rupert Holmes

1. Pre-cut plywood parts for the hull of a 40ft RM 1180.

Credit: Rupert Holmes

2. An entire boat length of topside panel scarfed and glued together. This is done off the boat, then the whole length is offered up to the jig.

Credit: Rupert Holmes

3. An RM 1070+ part way through construction, with the lower hull panels clamped and glued in place over the jig sections.

Credit: Rupert Holmes

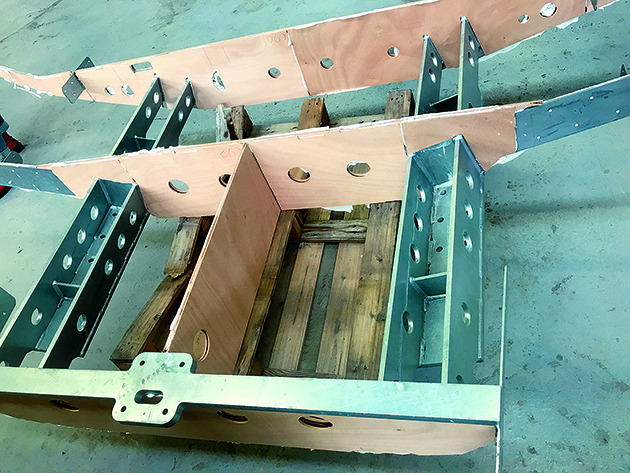

4. All RMs have a galvanised frame in the bilge that spreads the keel loads. This one is for the splayed twin keels of an RM 890+.

Credit: Rupert Holmes

5. An RM 970 hull with the outer skin now complete and removed from the jig. It won’t be turned the right way up just yet – there’s more work to do.

Credit: Rupert Holmes

6. Looking underneath the inverted hull, with bulkheads also now in place, as well as the steel frame structure for a single fin keel.

Credit: Rupert Holmes

7. The reinforced bow section.

Credit: Rupert Holmes

8. Applying epoxy laminate inside an upturned hull.

Credit: Rupert Holmes

9. The hull transferred to a different jig: note how the cut outs for the hull windows are used to support and eventually turn the structure.

Credit: Rupert Holmes

10. An upturned ply and fibreglass composite deck structure being fitted out.

Credit: Rupert Holmes

11. An RM 890+ hull being fitted out with tanks and other systems.

Credit: Rupert Holmes

12. Gleaming topsides after the painting is finished.

Enjoyed reading Why plywood boats are making a comeback?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-