Ali Wood visits the T Sails loft in Southampton to watch the sails being made for PBO Project Boat Maximus

Shortly before the Round the Island Race, one of the largest yacht races in the world, it’s all go at the T Sails loft in Southampton with sailmaker Tim Scarisbrick being inundated with sail repairs.

There’s a torn spinnaker on the shelf waiting to be fixed, and laid out on the floor is a triangle of charcoal-grey cloth that will be Maximus’s brand new genoa. It’s hot in the workshop but a breeze flows through the open plan room, and the many windows provide plenty of natural light for the three sewing machines, each inlaid into a table.

The bigger a sailmaker’s loft, the larger square footage of sail they can make, as every sail has to be laid out flat. Much as Tim would like to move the pillars in his workshop, he doubts that would go down well with the landlord.

“The future plan is to have a bigger place with a floor all the way through,” he says. “We’ll have all the sewing machines at the right height, plus lots of pasting tables, which really helps.”

Sailmaker Dan works on Maximus’s sail. Photo: Ali Wood

Not an inch of space is wasted; hanging from the ceiling are long plastic sail battens, which will be used for Maximus’s mainsail, and the shelves are packed with spools of thread, tape and tools. Dan is crouched over the genoa, trimming the leech with a huge pair of scissors, while Tim stands at a table, laying out the reef patches and checking them off against plans.

Whereas Tim can schedule in new sails, such as the mainsail, furling genoa and cruising chute for our Maxi 84 Project Boat, he can’t predict when his racing clients are going to turn up, pleading emergencies for an imminent race.

These panels will be stitched together to make Maximus’s genoa. Photo: Ali Wood

Being a professional racer himself, Tim empathises. He learned to sail as a child and then joined the Navy, where he became a part of their race team. He went on to run corporate racing events and crew on many high-profile yachts, including Alex Thomson’s IMOCA 60 Hugo Boss. However, the challenge for many professional racers is finding work at home, especially in the winter. Sailmaking allows Tim to keep up his racing career without being away for too long.

“As a racer, there’s nothing I hate more than a sail not doing its job properly,” he says, adding that he got into sailmaking because his friend at Kemp Sails persuaded him to do an apprenticeship.

“I’d never touched a sewing machine before,” admits Tim. “However, the alternative was teaching winter RYA courses, and that wasn’t for me, so I decided to give a go.”

Learning sailmaking

Tim really took to sailmaking, and after another summer of racing, was offered a job at Doyle Sails, where he became service manager.

After a few more years learning his trade, he set up on his own and now does everything from sail repairs to making new sails, which his racing clients will replace two or three times a year, sometimes more, depending on funds.

Watch the video

Watch the videoOften, old sails are passed down-the-line. Recently, for example, Tim did alterations for a corporate race boat, using sails from a former Grand Prix boat.

“All that was required was a clean height change. For a sail that had cost £10,000 originally they got a real bargain!” says Tim. However, he warns that you can’t just ‘rock up’ to a sailmaker with an ex-racing sail and expect it to fit your cruiser. “In many cases it won’t work. They have to be a very close fit to begin with. If you just take the bottom off, for example, the load paths will be in all the wrong places.”

When should you repair your sail?

So when is it time to replace a sail? “That’s a difficult question,” muses Tim. “It depends what you need it for. If it’s not torn it’s still technically a working sail, but if it’s shrunk round the edges and baggy in the middle its efficiency is going to be massively impaired.

“Dacron fibres, for example, break really easily. If you get a tear in the edge from where it’s folded a lot, you can pull at it, and damage it just with your bare hands.”

Tim had a sail in for repair the other day where the leech was split after constant flogging against the spreader.

“I ran my finger along it and knew it wasn’t worth repairing,” he says. “I could have replaced the strip but two weeks later there would be a hole inside the repair. It’s not worth throwing money at it.”

Sometimes it’s better to replace than repair – and that’s the reason there’s a new genoa for Maximus on the floor of Tim’s loft.

Visit to Bainbridge

Last month in PBO we visited Bainbridge to discuss sailcloth, and watched as a laser cutting machine chopped the roll of cloth into individual panels to be packaged and sent to Tim for stitching.

In PBO’s case Daryl Morgan of Bainbridge measured and designed the sails, but usually this is the job your sailmaker does. They can manage the process from start to finish. Sometimes, if Tim has a big project on, he and Daryl will go to measure the yacht together.

Watch the video

Watch the video“It’s helpful because we talk things through, and can both see the problems,” says Tim. “The hardest thing to get right are the rig measurements. There’s no reason to doubt a tape measure, but it’s one of those things that keeps you awake at night! Fortunately, you’d spot the error in the design process.”

What kind of sailing?

The first question Tim asks his customers is what type of sailing do they do.

“There’s no point selling someone some super fancy carbon, all-singing, all-dancing sails if all they’re going to do is day sail from the Hamble to Cowes with the kids,” he says. “It would be a complete waste of money.”

Budget is, of course, the second factor in choosing sails. You can build a sail for the same boat that can be four to five times more expensive depending on what it’s made of. Your desired lifespan for the sail is also a factor. For example, long-distance cruisers might want to pay more for a sail, making sacrifices elsewhere, because they need

something that will sail upwind efficiently; something Tim understands well.

“It drives me mad, trying to go anywhere with sails which you know aren’t working properly,” he says.

Of course, this comes with added cost. A tri-radial sail like Maximus’s genoa (where the cloth is cut to follow the load patterns on the sail) has a nicer shape than a cross-cut sail, and will hold it for longer. However, the labour that goes into it – because there’s a certain amount of sticking and stitching and a larger amount of cloth – is more.

Tradition and technology

Maximus’s rig was measured by hand with a tape measure, then the sails modelled using 3D software and cut at the factory with a computer-aided laser machine (see PBO December 2022). Tim and Dan then stitch every panel with sewing machines.

“We machine-sew everything here for the individual customer, there’s no alternative,” says Tim. “Every panel has been laid up by a computer specifically for this boat, but then it’s hand-stitched for the individual.”

That said, when it comes to racing sails, Tim points out that there have been huge advances in the larger lofts, with North Sails leading the way with 3Di membrane technology.

Though such technology is beyond the scope of most cruisers, it’s worth highlighting that 3Di sails are made of ultra-thin filament tapes moulded into a single membrane, and are designed to mimic the load-bearing and shape-holding qualities of a rigid airfoil wing. (You can watch videos at northsails.com).

In an age when we’re trying to reduce plastics, yet the professional racing industry still retires sails after a single race, increasing the longevity of performance sails sounds like a step in the right direction.

Woven polyester sails

Of course, Maximus’s woven polyester sails are designed for cruising not racing, and unlike racing sails, will last the lifetime of the vessel. They do, however, follow a trend passed down from the racing world, in that they’re grey, not white (though the racing world is apparently now switching to black!).

“Grey is really popular at the moment,” says Tim. “I recently made a grey set of sails for a client with a Westerly Centaur. They looked fantastic – plus you could spot him on the Solent from miles away.”

There is a small functional benefit, too, Tim explains: the yarns are dyed before they’re woven, and the dye decreases the porosity of the cloth.

For asymmetric sails, however, the visual design comes after production. Tim uses a firm called Ocean Art, who paint and print logos on sails. “People are much more open to different ideas these days,” says Tim. “The grey and white combination for mainsail and genoa is popular. I also recently designed a spinnaker that was black, white and orange!”

Sail test

A month later, Tim visited Maximus to fit the new sails. We invited PBO’s boat tester David Harding down to try them out, and here’s what he thought of our Maxi 84 Maximus.

Sailmaking step by Step

01 Sailcloth typically arrives in 60 to 70 individual panels which need to be unpacked, sorted and stitched together.

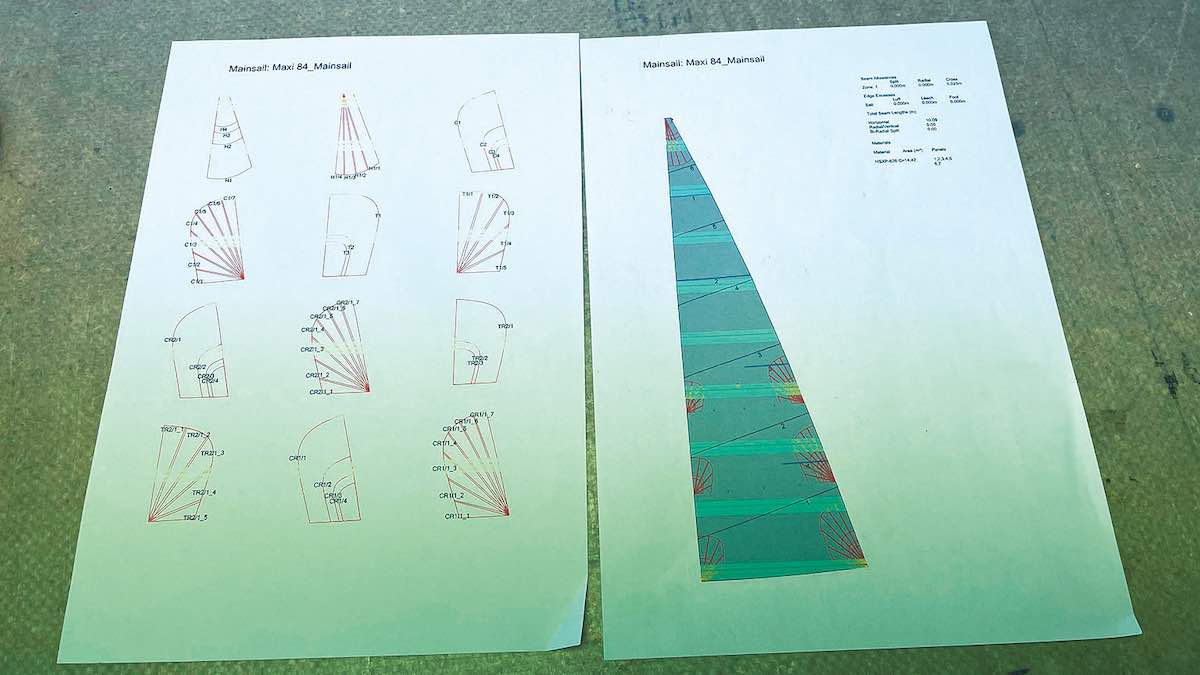

02 The sailcloth comes with a plan which Tim and Dan will refer to continuously throughout the build.

03 Labelled panels – this is clew reef patch No1 – are held together temporarily with double-sided tape.

04 The taped panels made of multiple pieces are then run under the sewing machine, one panel at a time, to secure their individual pieces together. Next, the panels are sewn together before the sail is laid out on the floor so surplus cloth at the edges can be trimmed away with heavy duty scissors.

06 A batten is pinned to the loft floor to help maintain a smooth shape during sail construction, especially where the panels are joined.