How do you combine trailability, performance and live- aboard comfort in a 26-footer? David Harding explains the secrets of the Bay Cruiser 26

Bay Cruiser 26: space, pace and practicality

As a starting brief it sounds demanding but achievable: a 26-footer that’s fast and fun to sail, simple to manage single-handed, light enough to trail behind a large car and with a flush bottom for easy beaching and launching.

And it should have a hint of retro in its lines.

That’s not all. It needs to be roomy, too.

Full standing headroom would be good, ideally in a raised saloon that gives all-round visibility.

Cockpit locker space to accommodate plenty of kit, including an inflatable dinghy with an outboard engine, is essential.

Full-depth lockers on each side of the cockpit in the Bay Cruiser 26. Credit: David Harding

So too is enough battery power to wind the keel up and down and to flush the loo, because we prefer to press buttons for the boring jobs.

While you’re working on the accommodation, we’d like a galley that slides away to maximise space in the saloon.

And fit a charcoal heater by the main bulkhead, routeing the flue through the heads to keep it nice and warm and dry.

Oh, and a fridge bigger than you’d find on most 40-footers.

Anything else? Yes, of course, but this will do for starters.

If you manage all that, we’ll be heading in the right direction.

This isn’t an exact précis of the exchanges between Matt Newland of Swallow Yachts and the owner of the first of the Bay Cruiser 26s, but it covers some of the areas they discussed during the development of what has to be one of the most interesting, practical and versatile little yachts to be launched in many a year.

Bay Cruiser 26: just the right size

As regular readers will know, Swallow builds the Bay Raider and Bay Cruiser range of dayboats and weekenders that combine a slightly traditional appearance with modern underwater profiles and construction methods.

Basil Papadimitriou has owned numerous boats including a Southerly 115, a couple of Gib’Seas and a Voyager 40 before he moved right down to a Pippin 20.

Then, wanting something with more get-up-and-go, he bought the Bay Cruiser 23. He liked it in many respects but reckoned something just a few feet longer would have the potential to provide everything he wanted for the foreseeable future.

This is how the idea for the Bay Cruiser 26 was conceived, though she was a 25 until the stern was raked the other way to become retroussé, extending the waterline and giving her a more modern appearance.

The bridle mainsheet system works well. Credit: David Harding

Despite this change, however, she retains the traditionally-profiled, near-vertical stem, simulated lapstrake construction (or genuine lapstrake

if you have her in plywood instead of GRP) and a short bowsprit.

So it’s very much a case of modern meets traditional. Add the raised coachroof, carbon spars, twin, transom-hung rudders and, in Basil’s case, carbon laminate sails, and on paper this boat sounds like incongruity exemplified – the nautical equivalent of a classic roadster colliding with an accessory stand in an auto shop and driving away with speed- stripes down the sides and a spoiler hanging off the back.

The remarkable thing is that, when you see her in the flesh, the Bay Cruiser 26 really does pull it off.

Not classically pretty, she’s nonetheless pleasing to the eye in an unconventional sort of way. At least that’s my view, and it’s one that others seem to share.

Subjectivity, however, plays no part when it comes to assessing her versatility: this is a boat that Basil has trailed to Morbihan, that he regularly lives aboard upon for days (and sometimes weeks) at a time, that has seen off most cruising yachts up to 30ft and in which he has a fully-functional office with a desk nearly 4ft (1.2m) wide and a view of the outside world.

Small is practical

Basil has been there and done it with larger yachts. ‘You have limited time and have to go to the same old places.’

Having also had a couple of trailable boats, he knew that trailability was the answer for him.

Between our two outings from his base in Chichester he had already taken a trip to France for the Semaine du Golfe in Morbihan.

Since then he has trailed to Falmouth – launching and rigging single-handed – and will later be heading across to the Scillies.

Making a 26-footer light enough to be easy to trail is one thing.

The challenges lie in also making it tough enough to withstand bouncing around on a trailer, roomy enough to provide ample living space and sufficiently fully fitted to be a comfortable home, especially given the beam restrictions for trailing.

After all, space, strength and comfort tend to mean bulk and weight – so what’s the answer?

Like the smaller Bay Cruisers, the 26 uses water ballast: this time the tank below the floor contains 750lt, supplemented by lead encapsulated in the bottom of her glassfibre daggerboard.

Carbon laminate sails are the owner’s choice. Credit: David Harding

Weight is also saved without compromise to strength by the use of vacuum-bagged foam-cored composites in the construction (unless you opt for the epoxy-ply alternative).

This boat is not built to be cheap: she’s built to perform to a standard.

The use of water ballast means that emptying the tank (by electric pump, unless you fancy around 30 minutes of pumping manually) brings the weight down by 1,650lb (750kg) to around 4,000lb (1,800kg).

With the water ballast weighing about the same as the four-wheeled trailer, the total weight behind the tow hitch is in the region of 2.5 tons.

This explains the weight – or, rather, the lack of it.

Like other boats of this length designed for trailing, the Bay Cruiser 26 has to be narrower than she might be otherwise in order to comply with the European maximum of 2.54m (8ft 4in).

Inevitably this leads to topsides that are not far off upright and to a fairly hard turn to the bilge, though she looks anything but slab-sided.

The volume for her living space is greatly enhanced by the raised coachroof over the saloon, which gives both standing headroom for a six-footer and a view forward.

We’ve touched on the accommodation already and will come back to it later, so for now let’s turn our attention to what she’s like under sail.

Fast Bay Cruising

Like her smaller sisters, the Bay Cruiser 26 is designed to perform efficiently.

She has a long waterline for her length (displacement/length ratio 110) and ample sail for her weight (sail area/displacement ratio 19.6).

Her hull is slippery.

The rig features a fat-head mainsail (there’s no backstay) and a minimal-overlap headsail with a close sheeting angle.

She also has carbon spars: less weight for easy raising and lowering of the mast, less heeling moment, less pitching, more speed, and more comfort.

The tip of her daggerboard plunges to 5ft 2in (1.58m) below the waterline – that’s a healthy draught for a 26-footer.

A daggerboard rather than a centreboard means no turbulence from a slot and, in this case, virtually no intrusion below decks because it’s incorporated into the main bulkhead.

A fully profiled section in glassfibre, it has 330lb (150kg) of lead encapsulated in the bottom to maximise the righting moment and allow the boat to recover from nearly 130° even with no water ballast in the tank.

Fully ballasted, she has an AVS (angle of vanishing stability) of close to 140° and an appreciably greater righting moment, to which the GZ curve showing the arm doesn’t really do justice.

Adjustable, padded backrests outboard of the cockpit coamings. Credit: David Harding

Of course, she could have been made faster – but not without becoming a different sort of boat.

For example, a bulb on the bottom of the keel would have lowered the centre of gravity and allowed a reduction in the ballast (and therefore total) weight.

She would then have sat higher on the trailer, leading to immersion of the bearings and brakes during launching and recovery, and settled at an angle when dried out on a hard bottom.

Performance-enhancing features have been incorporated where they don’t alter the ethos of the design: she’s an easy-to-live-with trailable cruiser offering features that have rarely – if ever – been combined in one boat.

There’s little doubt that she will run rings around most modern classics and trailable cruisers of similar length, not that most modern classics or trailable cruisers are remotely comparable.

For example, what does she have in common with the Cornish Crabber 26?

Her overall length – that’s about it.

To see how she sailed I headed out with Basil on two occasions.

Our first outing in about 25 knots was curtailed by gear failure that was in no way the boat’s fault.

A Code 0 can be used for extra punch once the sheets are eased. Credit: David Harding

Second time out we were met by a little less breeze from the opposite direction, giving us the opportunity for plenty of short tacking down the harbour.

This is a boat that immediately makes you feel at home.

She’s respectably quick and close-winded (we made around 5.5 knots on the wind, tacking through 80°) and nicely responsive without being remotely twitchy.

If you have any concerns about carbon spars, high-aspect daggerboards and fat-head mainsails, you really need to think again.

She’s a doddle to sail yet thoroughly rewarding when you get her in the groove.

Like many boats designed with performance in mind, the Bay Cruiser 26 is far, far easier to manage than boats that are too slow and clumsy to get out of their own way.

The twin rudders are nicely balanced and the steering gives a positive feel, though inevitably the linkage leads to a little more friction and play than with a single blade.

Twin rollers and a neat arrangement for the anchor. Credit: David Harding

At normal angles of heel, there’s virtually no weight on the helm.

It only begins to load up if you push her beyond 30° or so.

Even then, the leeward rudder normally maintains its grip until the gunwale is awash.

Given that we were sailing with no water ballast – Basil has never felt the need to fill the tank – I refrained from pushing her too hard despite the impressive stability curve.

By the time the windows were getting wet, I eased the mainsheet and let her come back to a more comfortable angle.

If you’re making a coastal passage in 25 knots you might choose to use the ballast.

Otherwise, you’ll have more fun if you leave the water in the ocean.

On the way down the harbour, we left a 35ft cruiser for dead and only narrowly lost out to a well-sailed Solent Sunbeam (a racing keelboat of similar length) from the local fleet.

We knew how to dodge most of the flood tide but the Sunbeam’s crew, being familiar with every bump in the bottom of the harbour, went a few yards further on each tack and pulled out a few yards on us.

We reckoned half their margin was down to the tide-dodging and half to the boat. It was a pretty good yardstick to measure ourselves against.

All you have to learn with the Bay Cruiser 26 is to sail fairly deep out of the tacks to build up speed before hardening back up; otherwise, it takes a few seconds for the high aspect-ratio daggerboard to regain its laminar flow.

Downwind, she’s off: 7 knots appears on the log straight away and I’m sure she would need no excuse to start surfing in any waves.

Bay Cruiser 26: ergonomic

With a relatively small headsail and a pair of Harken 15 self-tailers on the coachroof, tacking is simple.

For the mainsheet, Basil has elected to have an over-length boom so the sheet can be taken to a bridle at the stern and then along the boom to a block and cam cleat.

It’s a simple and efficient system that works well (as long as you have enough purchase on the kicker) and keeps the cockpit nicely clear.

Practical and logical though it is, Matt’s probably right in imagining that some owners will prefer a conventional centre-sheeting arrangement with a pedestal on the cockpit sole.

It’s this latter system that I have changed to something similar to Basil’s in the interests of increasing the mainsail’s efficiency, saving rope, minimising friction and de-cluttering the cockpit, but each to his or her own…

The outboard hinges up in an open-backed well which, on production boats, can be filled with a fairing plug. An inboard diesel is also offered. Credit: David Harding

I couldn’t fault the helming position. The coamings provide a comfortable perch and Basil has adjustable padded backrests rigged up between the stanchions.

One change I would make is to the standing rigging. The Dyneema lashings used in place of bottlescrews don’t apply enough tension: there’s too much forestay sag and any tension on the lowers removes all the pre-bend.

Although the idea is to keep rigging and trailing as simple as possible, it’s never going to be a 30-minute job on a boat of this size.

Bottlescrews would earn their keep.

At this point, it’s worth pointing out that Basil’s Bay Cruiser 26 is in mahogany plywood; GRP versions are available.

Partly because of the construction (Okoume plywood would be lighter) and partly because of all the kit Basil has fitted and likes to carry on board, Muddy Waters is around 660lb (300kg) heavier than the production boats are likely to be.

Since she floats nicely to her lines and doesn’t exactly hang around under sail, it bodes well for what’s to follow.

Details on deck

One area where the Bay Cruiser 26 stands out is attention to detail.

In this respect, as in many others, she has more in common with larger, semi-bespoke cruising yachts than with most production boats – particularly those in this size range, where profit margins can be low and keeping costs to a minimum is often an all-too-obvious priority.

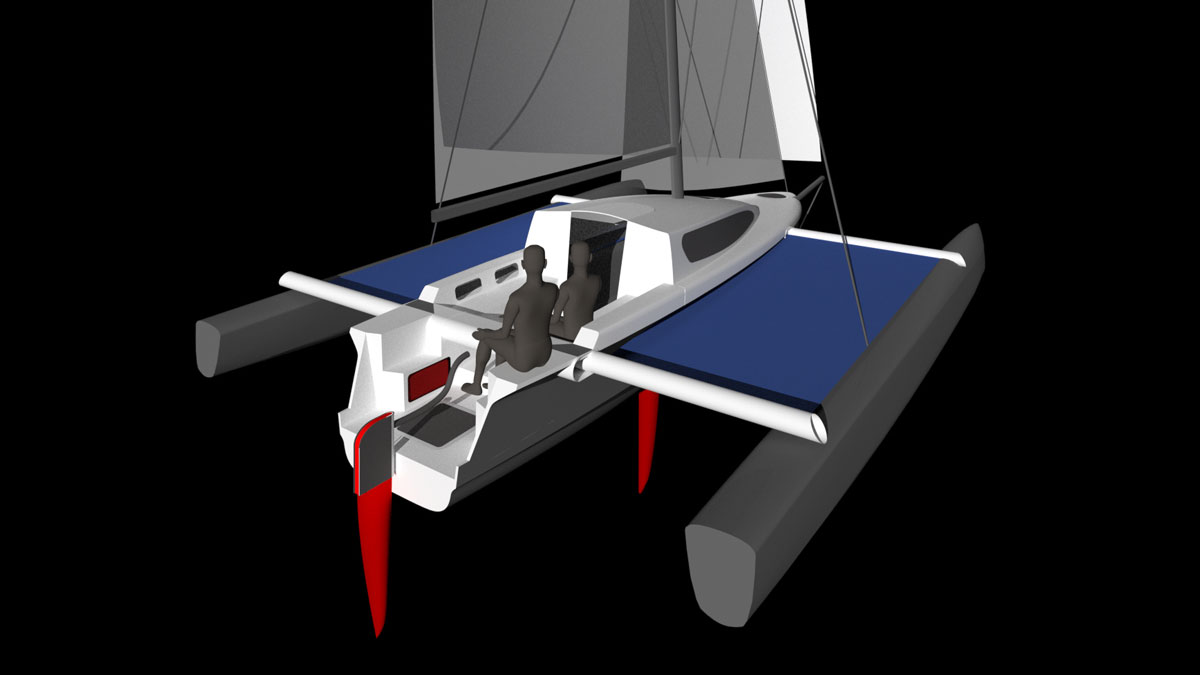

Sail plan of the Bay Cruiser 26

Neat features are everywhere you look. One example is the way the nav lights have been set into the bowsprit moulding on each side.

The bowsprit (which will fold up on future boats) also incorporates twin rollers and a stainless steel anchor.

Throughout the boat, every angle, every recess and every handhold has been given a lot of thought, as has the choice and position of the hardware.

You can’t scrutinise and test everything on a couple of day-sails, but it all looked pretty well up together.

Accommodation on the Bay Cruiser 26

Below decks, the pale oak trim, simulated tongue-and-groove, large window area and off-white finish to the woodwork (some of which will be mouldings on the production boat) create a light, airy and welcoming feel.

Stepping down into the saloon you still have a view of the outside world and anyone within an inch of 6ft can stand up.

The saloon offers room to sit, stand and sleep, lots of light, plenty of handholds, neat finishing and stowage everywhere. Credit: David Harding

Here you find a berth on each side and a fully-equipped galley (complete with twin sinks) that slides out from under the cockpit seat on the starboard side and allows you to work while standing in the companionway, under the sprayhood with the hatch open.

Unless you have an inboard engine, the fridge-freezer slides out from beneath the bridge deck, as does the giant gash bin and the pull-up larder or veg store.

A table can be fitted in the middle and, on Basil’s boat, a special one-off chart table-cum-desk hinges down to port.

A pull-out galley complete with twin sinks and good work space. Credit: David Harding

Then the saloon table acts as a base for a seat – and there’s the office.

Never before has hinging and sliding been used to such good effect.

Stowage is everywhere and no space is wasted.

Forward of the bulkhead – and the charcoal heater – are the heads, a hanging locker and the forecabin, all fitted out in the same manner.

Verdict on the Bay Cruiser 26

By any standards, this is a remarkable little boat.

Her space, performance, versatility, practicality, trailability, standard of finish and attention to detail really do set her apart.

Whereas Swallow’s smaller models have been fitted out more in the style of camper- cruisers – that’s what they’re designed for and they do the job very well – the Bay Cruiser 26 set new standards, both for the builder and for boats in this size range when she was launched.

I can see her appealing to a wide audience and especially to people moving down from larger boats.

Pointer 22: the refreshingly simple trailer-sailer

Light, slim and fast, the Pointer 22 is a no-nonsense day-sailer-cum-weekender, says David Harding

Haber 620: a trailer sailer like no other

How on earth do you get full standing headroom in a trailer-sailer that really sails? David Harding meets the Haber…

Viko 21: A trailer sailer that sets the standard

Costing from £23,000, the Viko 21 seems remarkably good value – but what does she offer apart from economy? David

First look at the new Astus 26.5

The first images of the new Astus 26.5 have been released. The yacht will be available towards the end of