Kerry and Fraser Buchanan dust off a 30-year-old ambition and ready their Barbican 33 to sail to Greece via the French waterways

Two fogies were going south. My husband Fraser and I were both in our late 50s, one disabled and the other recovering from radiotherapy for cancer, but were determined to make our dream voyage a reality.

It had started 28 years ago, while sweltering in a heatwave throughout my first pregnancy, when I read a PBO article about someone who took their yacht on an idyllic trip through the French inland waterways, north to south.

From those pages, the seed of inspiration was planted: one day, we’d sail our own boat to the Mediterranean via the French rivers and canals, turn left and follow the rising sun.

For the next few decades, life got in the way. We had a young family, jobs, schools; the usual rat race stuff.

New Raymarine chart plotter for their dream voyage to the Med. Credit: Kerry Buchanan

We continued to sail with the family in a variety of dinghies and bigger boats, but the time was never quite right for our dream voyage.

Finally, in 2018, we went in search of the perfect boat to carry us south.

We needed a sea-kindly boat that could cope with the challenging waters around the coast of Northern Ireland, set up for single-handing as much as possible because we will always be short-handed as my disability makes me less useful as a deck hand than I used to be.

Fraser and I get on really well (I jump up and down and shout a lot; he nods and goes on doing his own thing), so we weren’t too worried about having a massive interior.

Cruiser criteria for a dream voyage

Many couples who go off sailing full-time opt for a boat with vast space but we decided 30-36ft would do us nicely.

Enough room for comfort, plenty of hand and hip-holds for moving around down below in a seaway, small enough to nip into the shorter pontoon berths in marinas.

And cheaper, of course, to buy, to maintain, to fuel, and to berth.

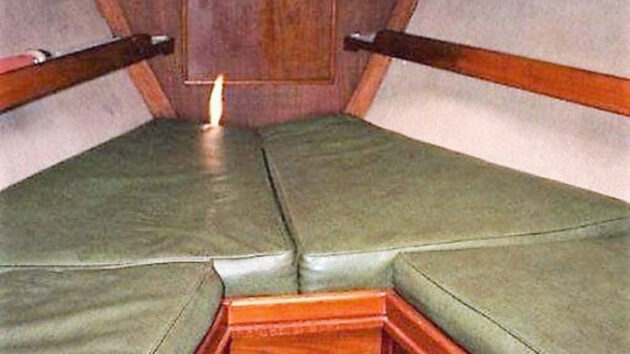

Original vinyl upholstery in the saloon. Credit: Kerry Buchanan

We trawled through boating magazines and websites, discussing every vessel for sale that met our criteria, and discarding most of them.

We had a limited budget and needed to spend our money carefully.

After a few false starts that involved flights from our home in Northern Ireland to England, rented cars, and traffic jams on the M25 followed by horrendous surveys and despair, we finally discovered Barberry almost on our doorstep.

She is a 1984 Maurice Griffiths-designed Barbican 33 with a long keel and centreplate.

New saloon upholstery should suit hotter climates. Credit: Kerry Buchanan

With the plate up she draws around 1.2m (the maximum published depth for the routes we planned to take is 1.8m), yet she is strong, stable, and sails comfortably, albeit not very swiftly with us in charge.

As our projected route was through the French inland waterways, draught was a key concern, but she also needed to be able to cope with the rough waters between her home port in Bangor, County Down, and Northern France.

Barberry’s the perfect boat for this challenging role with her long keel and narrow form, slipping through the waves without slamming.

A vessel for a dream voyage

Barberry had been out of the water for a few years, but she had been well cared for by her previous owners.

A full survey confirmed our confidence in her condition. We sailed her back from Coleraine to Bangor and she behaved perfectly.

We sailed Barberry just as she was for the first couple of seasons, to work out what, if anything, we needed to upgrade.

We each made a list. Fraser’s was quite short; mine ran to several pages.

I have a spreadsheet of the work we have done (which I kept secret from Fraser until recently for the sake of his sanity) and the amount we racked up is quite staggering.

Many readers will question our priorities, especially perhaps the bow-thruster, but I’d remind all that we are both old, I am disabled, and after decades of sailing various boats together, we feel we have nothing left to prove about boat handling. We deserve our comforts. Besides: long keel.

Others thinking of doing something similar will have their own priorities, probably very different from ours, but that’s what makes boating so interesting: the infinite variety of boats and the lucky people who sail them.

Necessary gear for our dream voyage

On our delivery trip, we discovered that our eyesight had worsened during the eight years we’d been boatless.

Tiny 4in GPS screens had never been a problem before but now we could barely read them, so we fitted a modern Axiom 9 chartplotter.

It was life-changing, but it was also the beginning of the slippery slope.

Old Thorneycroft 35 HP engine removed. Credit: Kerry Buchanan

We ended up with AIS, new autopilot, new radar, bigger solar panels to help run all the gizmos, a better battery charger, etc.

Our largest single upgrade costs were the engine, new upholstery and the bow-thruster. Of those, two were definitely luxury choices.

In warmer climates, the original vinyl would have been awful to sit on or sleep on (imagine the sound of sweaty flesh peeling free from hot plastic).

The engine, to us, represented peace of mind; plus, it was quieter and more economical than the original Thornycroft which was beginning to show a reluctance to start in cold weather.

The new engine, a Beta 35hp. Credit: Kerry Buchanan

Since fitting the bow-thruster, docking has been a pleasure again. I hardly ever deploy it, but when it is needed, it is a fabulous piece of kit. And it was to earn its keep in the French canals.

Another fairly big-budget change was the fridge. Barberry came with a cavernous insulated cool box.

We considered fitting a front-loading fridge, but there would have been a sacrifice in internal capacity, and we worried about the loss of cold air every time we opened the door.

Besides, why waste a perfectly functional cool box? Fraser added loads of insulation around the outside, and we opted for a keel-cooled fridge to increase efficiency and keep power demand to a minimum.

Apart from having to drill a hole in the hull, which he hates doing – so a skilled friend did it – the installation was seamless.

Now we just need to remember not to antifoul the sintered bronze cooling plate.

A holding tank was vital for the French waterways. Credit: Kerry Buchanan

We did not initially add a new seal to the hinged lid of the fridge, but that job was required as we sailed south, to prevent warm air from getting in.

Next Fraser turned his attention to fitting a diesel heater. We still had several Northern Irish winters ahead of us before our departure date and even the warmest parts of the Med can get chilly at night, especially in spring and autumn, so we wanted to be prepared.

Fraser tried to resurrect Barberry’s elderly Volvo diesel heater but couldn’t get the thing going, so we budgeted for a replacement. Again, much research.

Tight space for fittings. Credit: Kerry Buchanan

The price of an Eberspächer system was too steep for our groaning budget, yet we were wary of the very cheap heaters on eBay.

We opted for a Planar heater. Typically, the ductwork that came with the heater was wider in diameter than the existing ductwork, which led to Fraser playing a solo game of Twister as he contorted his upper body into tiny cupboards and lockers, drilling slightly wider holes six times through various bulkheads, while I sat at the chart table writing my crime novels.

Having chosen the slightly more expensive version with a controller that can be remotely operated by smartphone, we can turn the heating on as we drive through the marina gates, knowing the boat will be toasty warm by the time we arrive. And hopefully not on fire.

We were very careful to ensure there is nothing flammable near the exhaust pipes that run through the cockpit locker, or that anything might fall onto the exhaust.

So, with somewhere cool to store our food and somewhere warm to toast our toes, things were looking up.

Tank expansion

Since we intended to spend time at anchorages, we wanted to increase our freshwater storage and add a holding tank (necessary for the French inland waterways and for the Med).

The boat came to us with a single, pyramidal 200lt flexible tank beneath the V-berth, at the bow, but the bow-thruster tunnel meant we’d lost a lot of that space.

New freshwater tank. Credit: Kerry Buchanan

We had around 100lt of useable freshwater supply. Fraser decided he could squeeze in a 70lt rigid tank on either side beneath the V-berth.

He linked them, and a new 100lt flexible tank, so that we could hold roughly 240lt of fresh water.

While he was clambering around in the bilges, he replaced all the freshwater hoses too.

Many Mediterranean countries are very strict about black water discharge, and in the French canals it is much the same, so we needed a holding tank.

New pipework for the holding tank. Credit: Kerry Buchanan

For a 33ft yacht of the old school (narrower in beam than most modern production yachts), Barberry has a surprising number of useful nooks and crannies.

Fraser managed to fit a 60lt holding tank beneath the sink in the heads, and while he was at it, he replaced the Blakes toilet pump with a new one, keeping the original for spares.

The Blakes Lavac toilet is a marvel of engineering.

Extra freshwater tank capacity meant more time at anchor. Credit: Kerry Buchanan

We had one in a previous boat, and we have had a shiny new modern-style toilet, too. I can tell you which I prefer.

We did not want to get rid of the Blakes, but Fraser was not sure how he could incorporate it into the holding tank pipework.

In the end, the Blakes proved to be easy to adapt, and the addition of Y-valves meant that we could now pump out as before, or divert to the holding tank.

The tank can be discharged at sea, or emptied at a pump-out station.

Automatic fire extinguisher fitted in the engine bay. Credit: Kerry Buchanan

Even boating newbies can manage the Blakes system if they follow the guide printed on the wall behind the basin: 8-10 steady pulls of the lever, wait for a slow count of five, then 5-6 more full pumps.

The only issue is the vacuumed-down toilet seat when someone forgets to ask, “Anyone else need to go or will I flush?”

Still, the vacuum does release eventually and there have been no (admitted) cases of damp underwear – so far.

Making chaps

One of the most time-consuming jobs Fraser took on was making dinghy chaps. The dinghy that had come with Barberry was an Avon Rover 2.5 that seemed very small, especially with my dodgy joints and balance.

I refused to clamber into it, especially in icy, northern waters. Inflatable tenders were like hen’s teeth in 2021, post-Covid, but eventually, we tracked down what felt like the last Honwave 2.7m in the UK and ordered it.

Fraser fitted davits to Barberry’s aft coaming, so we were all set, but we wanted to protect our investment.

Harsh Med sunlight can wreak havoc on PVC tubes, and the Bangor seagulls, with their diet of mussels and oysters, drop sharp shell that could easily pierce the inflatable floor.

New solar panels, total of 200W. Credit: Kerry Buchanan

We’d seen dinghy chaps on YouTube sailing channels based in the Med but they seemed impossible to find locally, so DIY it had to be.

My arthritic hands mean I find sewing painful, even using a machine. Besides, Fraser had time on his hands! He had been diagnosed with cancer in 2021 and was off work while he received radiotherapy, before eventually taking early retirement in 2022 through ill health.

He has never been one to sit idly, so he threw himself into this, to take his mind off the medical stuff. I showed him how to use my heavy-duty sewing machine, and ordered some canvas from eBay, cheap enough for it not to be a disaster if it was wasted, but of reasonable quality so that if the chaps worked they’d be useful.

That dinghy remained inflated in our dining room for months (all the furniture pushed to one end) while Fraser draped strips of canvas over the tubes and drew on it with tailor’s chalk.

It was a mammoth task but we now have a beautiful, well-protected dinghy with a removable cover.

Plus a matching bag for storing the rolled-up dinghy, hatch covers, winch covers, etc.

Final stages

By now we had added a new liferaft, fire extinguishers (including an automatic one for the engine bay), an automatic bilge pump, new masthead lights and VHF aerial, and engine bay soundproofing.

The last few items included personal AIS man-overboard beacons, fans and wind scoops.

We decided to keep our trusty CQR anchor for the time being. With care (and 80m of 8mm chain) we should be okay.

Liferaft at the ready. Credit: Kerry Buchanan

We intended to install some form of wifi for the boat, and a good anchor alarm, but those could wait until we’d saved up.

We thought about installing a bimini but Barberry’s radar arch, the backstay and the mainsheet made this tricky.

Instead, we decided to make do with a parasol once we’d dropped the mast for the French waterways, then decide how much cover we actually needed over the cockpit once we were in the full Med sunlight.

We tried to do things as cheaply as possible.

Original V-berth upholstery. Credit: Kerry Buchanan

The davits were the cheapest we could find that were rated to take the size of the dinghy and outboard we’d be using with a reasonable safety margin.

Many of the jobs were carried out by Fraser, with sticky epoxy fingerprints all over the varnished woodwork to prove it, but we definitely needed professional help with much of the electronic gear and the bow-thruster.

For this, we are indebted to Brian Hanna, who keeps us entertained with his dry humour.

New upholstery in the saloon’s V-berth. Credit: Kerry Buchanan

We also used a professional rigger for the standing rigging, and the engine was fitted by Michael of Coburn Marine Engineering.

I decided to use a professional upholstery company to do the cushions and bedding as the costs I was coming up with for a decent DIY job were almost as much as the professional quote, and we would still have been waiting for it to be finished in 2025 if it had been left to me.

Bon voyage

We were almost ready now. The family farm was ‘sale agreed’, we’d drastically decluttered and moved into a rented bungalow closer to the boat at Bangor.

Our adult children agreed to pet sit and strive to survive without mum and dad for a few months, and suddenly we were free.

Barberry had a last lift out in March 2023, then on the next decent weather window, we slipped the lines and waved goodbye to Northern Ireland, bound for Greece.

- Over the next few months we cruised 2,500 miles visiting Ireland, Wales, England, France, Corsica, Sardinia, Sicily and finally Greece, exploring new places, and meeting new people. In August 2023 we left Barberry tucked up in Greece for the winter, and flew home. However, we have caught the cruising bug and the only cure I know of is to slip lines as often as possible and ghost away into the sunrise.

The boat gear we upgraded for our dream voyage

Beta 35hp engine. Reason: The original Thornycroft was not always starting, especially when cold. Approx cost: £9,000 Verdict: We could have reconditioned the old engine, but the peace of mind was worth every penny. We motored a lot on this voyage, not least through the entire length of France from top to bottom.

Bow-thruster. Reason: Long keel. Need I say more? Approx cost: £4,500 Verdict: Paid for itself scores of times in the canals, and again when we were Med mooring, giving a degree of control in reverse that just isn’t possible with a long keel boat otherwise.

Keel-cooled fridge. Reason: No fridge on boat, just a 1980s coolbox with little insulation. Approx cost: £880 Verdict: Not sure how we’d have survived without it. Shops were few and far between both on the French waterways and in the Med, and we’d probably have keeled over from food poisoning without a fridge (forgive the pun).

Diesel heater. Reason: Original one damaged beyond repair. Approx cost: £1,300 Verdict: May never use the heater again now the boat is in the Med but was a lifesaver in April in UK waters. It also allows us to do a status check remotely, now we’ve left the boat thousands of miles away.

Solar panels, total of 200W Reason: Old ones worn out. Approx cost: £450 Verdict: Without these we’d have been far more dependent on shore power for running fans and fridge. They enabled us to stay at anchor for much longer periods.

Electric windlass. Reason: Replaced manual one. Approx cost: £1,400 Verdict: With 80m of 8mm chain, a manual windlass would have been hard work and slow in deeper anchorages. This made life so much easier and made anchoring a pleasure.

Holding tank. Reason: Needed for Med and for French canals. Approx cost: £700 Verdict: Essential, especially in the Mediterranean.

Extra freshwater tanks. Reason: 200lt flexible replaced with 100lt flexible and 2 x 70lt hard tanks. Approx cost: £800 Verdict: A total of 240lt freshwater combined with the UV steriliser and filter gave us tasty drinking water without having to carry heavy bottled water. A watermaker is next on our wishlist!

Accuva ArrowMax 2.0 UV water steriliser. Reason: Water from tanks tastes unpleasant. Approx cost: £600 Verdict: So worthwhile. Water was delicious and saved us a lot of effort. We filled water bottles from the tap and kept them in the fridge so we had plenty of cold water.

New upholstery and foam including memory foam bed mattresses. Reason: Old foam had flattened, and the vinyl fabric was sweaty, even in Ireland. Approx cost: £5,000 Verdict: An expensive item, possibly a bit of a luxury buy, but the new seating is cooler and more hardwearing, and the memory foam bed mattress was far more comfortable to sleep on.

New dinghy and davits. Reason: The old dinghy was quite small and felt unsafe and the boat didn’t have any davits. Approx cost: £1,450 Verdict: The davits saved us from having to choose between towing and hoisting the dinghy onto the boat. It was great to have the tender readily available but it was a bit of a nuisance in marinas as we had to drop it down and tie it to the bow each time.

Safety items: liferaft, EPIRB, MOB beacons, fire extinguishers etc. Reason: A liferaft isn’t mandatory for pleasure vessels under 13.7m but we felt happier to have this, the fire extinguisher and emergency alert gadgets. Approx cost: £2,000 Verdict: These are items we would have added to our inventory anyway, but we were grateful to know they were there during the long voyage and even more grateful that we didn’t need to use any of them!

Want to read more articles like How to prepare your boat for a dream voyage?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter