Ali Wood learns how a shy 19-year-old – one of James Wharram’s ‘five girls’ – became a designer, skipper and head of a multihull business

Hanneke Boon is ‘carving out a new stage in her life’. Two years after the death of her business and life partner, James Wharram, she’s crossed the Atlantic, given presentations and continues to send plans to amateur boatbuilders across the globe.

“I’m very much active at the moment,” she says. “I recently gave a talk at Flushing Sailing Club and it went quite well. James always was the one doing the talks but I’ve come to realise maybe actually I’m quite good at it.”

Wharram, who contributed to PBO, was a pioneer of offshore multihulls.

His business, James Wharram Designs, which he ran with Hanneke, has sold over 10,000 plans for ply-epoxy catamarans, winning him the Ocean Cruising Club Award of Merit in 2012.

James’s unorthodox life, on and off the drawing board, made him an icon and, at times, a controversial figure who challenged the sensibilities of the establishment.

James Wharram and Ruth on his first boat Annie E Evans. Credit: James Wharram Archive

But it was his innovative designs, combined with Hanneke’s draughtsmanship, that really made yachting history.

The story begins in 1956, 12 years before Hanneke Boon entered James’s life.

Inspired by the ancient Polynesians, 28-year-old Wharram made his first Atlantic crossing on a 24ft ‘double canoe’ Tangaroa, with partners Ruth Merseburger and Jutta Schultze-Rohnhoff.

Three years later, the trio completed the first west-to-east transatlantic by multihull on 40ft Rongo, which they’d built in Trinidad.

“The two girls got on very well together, they were happy to share their man,” James wrote in his 2020 autobiography People of the Sea, which he co-authored with Hanneke Boon.

The self-built Tangaroa in Falmouth, Cornwall. Credit: James Wharram Archive

However, on returning with two ‘German fräuleins’ and baby son Hannes, the 4,500-mile voyage from New York was ignored; his pioneering achievement in yacht design was overshadowed by his personal life.

“Whether it was my ‘too early’ path into the sexual revolution of the ‘60s and 70s’… or my insistence on basing my designs on the sailing canoes of the ancient Pacific, it is so long ago I can’t be certain,” he said. “Added to this I was from the north of England and ‘yachting’ was largely the province of southern privileged classes.”

Wharram dismissed the claim he was part of a social movement; rather he was ‘living in a natural or open Polynesian way, as first recorded by Captain Cook and Bougainville.’

In the spring of 1961 James, his ‘two girls’ and Hannes set sail from Dún Laoghaire, Ireland, bound for the Pacific. Tragically, Jutta, Hannes’s birth mother, struggled with mental illness.

In an episode triggered by World War II trauma, she threw herself from a tower in Gran Canaria.

James Wharram at the helm of Tangaroa in the Bay of Biscay on the way to crossing the Atlantic. Credit: James Wharram Archive

“Maybe with present day knowledge, she could have had therapy and recovered. At the time such therapy did not exist,” said James.

Following Jutta’s death, James gave up his plans for the Pacific and together with Ruth and Hannes, sailed 10,000 miles around the North Atlantic on Rongo. “While most of my body and brain suffered in shivering misery, a small section of it exulted in Rongo riding the storm,” wrote James.

It would be another 33 years before he and Ruth finally made it to the Pacific, the home of the Polynesian craft that had shaped his designs and inspired a lifetime of adventure.

Tangaroa was 24ft long. Credit: James Wharram Archive

The man who sailed into Dún Laoghaire harbour in August 1962 was a very different one to the son of a construction worker who’d left six years earlier.

Rongo’s voyage – which James described as ‘stormy, hard and rough’ – would forge him into a fully-fledged catamaran designer.

He dreamed of further catamarans that would ‘dance over storm-tossed seas’.

Chief of them all, he declared, would be his ship Tehini, meaning ‘darling’ in Polynesian. It would be lighter, stronger and faster.

However, it would take Wharram ‘three confused, sometimes dark, sometimes exciting years’ to get there.

In 1963 his father offered a helping hand by commissioning a 20ft trailerable catamaran. James designed and built him a ‘Wharcat’. Sadly it capsized on its maiden voyage.

“I was shocked, horrified that I had wasted my father’s money,” he recalled. “My father just put his hand into his builder’s donkey jacket pocket… and said, disgustedly, with no criticism, no emotion: ‘and my bloody cigarettes are wet too.’”

After losing Jutta, abandoning his Pacific dreams and his rejection by the yachting establishment, James was distraught: “That capsize deeply disturbed me. It brought to the forefront of my consciousness ‘who or what was I?’.”

However, ever practical Ruth – one of the trümmerfrauen or ‘rubble women’ who’d helped rebuild post-war Germany – urged him to write a book.

While Ruth got a job to support them, James rebuilt the Wharcat, finished his ‘love story’ Two Girls Two Catamarans, and sold his first commission, a 35ft Tangaroa, to a railway engineer he met on Deganwy beach in North Wales.

Hanneke Boon helps her father build a Wharram catamaran at age 14. Credit: James Wharram Archive

In 1968 James rented space on Deganwy Quay, a former slate dock, and started work on the boat of his dreams, 50ft Tehini, one of the largest catamarans of the time.

It was during the build that he met Hanneke Boon, who would later join him as his co-designer and partner, and with whom he’d share his life.

Hanneke Boon grew up in Amsterdam in a family where boats were the centre of their lives: “Simple, small boats that we took sailing on weekends and holidays,” she recalls.

“My father instilled in me and my two sisters the joy of being on the water without needing the luxuries of city life.”

Gaining popularity Wharram’s catamaran designs were fast gaining a fanbase and Hanneke’s father, Nico, an enthusiast, took the family in 1967 on a camping holiday to Wales to meet James.

It was here 14-year-old Hanneke first met charismatic boatbuilder Wharram.

Buoyed by their summer adventure, the Boon family returned to Amsterdam with plans for a 22ft Wharram catamaran. “It gave me my first experience of boatbuilding,” says Hanneke.

James Wharram working on Tehini’s sails. Credit: James Wharram Archive

In the following two years, the family returned to help with the building of Tehini. The construction, beautifully documented on a Bolex cine camera by Ruth, captures the romance and free spirit of the era.

Wharram describes his clan of multi-national volunteers, including the Boon family, as: “A group of practical dreamers… captivated and willingly enslaved in the building of Tehini.”

On an estuary at the foothills of Snowdonia, there could be few places more beautiful to build a boat. The project attracted artists, writers, designers and craftspeople from all over the world.

Once Tehini was finished James and crew sailed to Hanneke’s home in Holland, where a large group of Wharram catamaran builders gathered to greet them, including Nico Boon who by now was James’s agent.

As a girl, Hanneke Boon showed promise in art, mathematics and science but claims to have taken the ‘easy option’ of art school.

Hanneke Boon worked on the Tehini build before setting sail with Wharram, aged 19. Credit: Hanneke Boon

“James was really impressed by my drawing skills. James never drew plans. He had ideas; lots of ideas and technical knowledge and building skills but he was not a draughtsman so that’s where I came in.”

Two years later, aged 19, Hanneke received an invitation to go on an ocean voyage with James Wharram and his crew. “It was all really quite exciting… I’m not sure whether my parents were completely happy with this but I made the decision so that was that,” she says.

Joining her would be Ruth and three other women ‘collected’ from Tehini’s build. “I was off across the Atlantic; this was the beginning of adult life and led me to become a boat designer. It was a lifestyle where I could use all my talents – sailing, drawing, boatbuilding, making things, design and mathematical analysis.”

In People of the Sea, Hanneke Boon describes the Tehini crew as an ‘incredibly loving group’ into which she was accepted. Maggie was the ‘mother goddess’, Ruth ‘sensible’, Lesley ‘domestic and funny’ and Nuala the ‘reader and conversationalist’.

“James, who we called Jimmy, was in the prime of his life, a very powerful, magnetic person, too big in every way for one woman to handle and not be overwhelmed,” wrote Hanneke. “I was shy and didn’t say much, but loved the sense of ‘group feeling’. I didn’t just fall in love with Jim, I fell in love with all of them.”

Tehini launch from Deganwy Quay. Credit: James Wharram Archive

With the Tehini voyage ended, James and his partners formed a boatbuilding company in Milford Haven, where Hanneke excelled as a draughtsman.

“James managed to make us all feel special,” she recalls. “He brought out our innate abilities and encouraged them.”

They researched and developed glassfibre construction, building prototypes and trying out new ideas.

“We were trying to develop foam sandwich construction but didn’t think it was a technique that was particularly nice for self-builders,” says Hanneke. “There were issues that made it difficult to keep a good shape… but in fact, the boat we built is still around. It belongs to a Frenchman.”

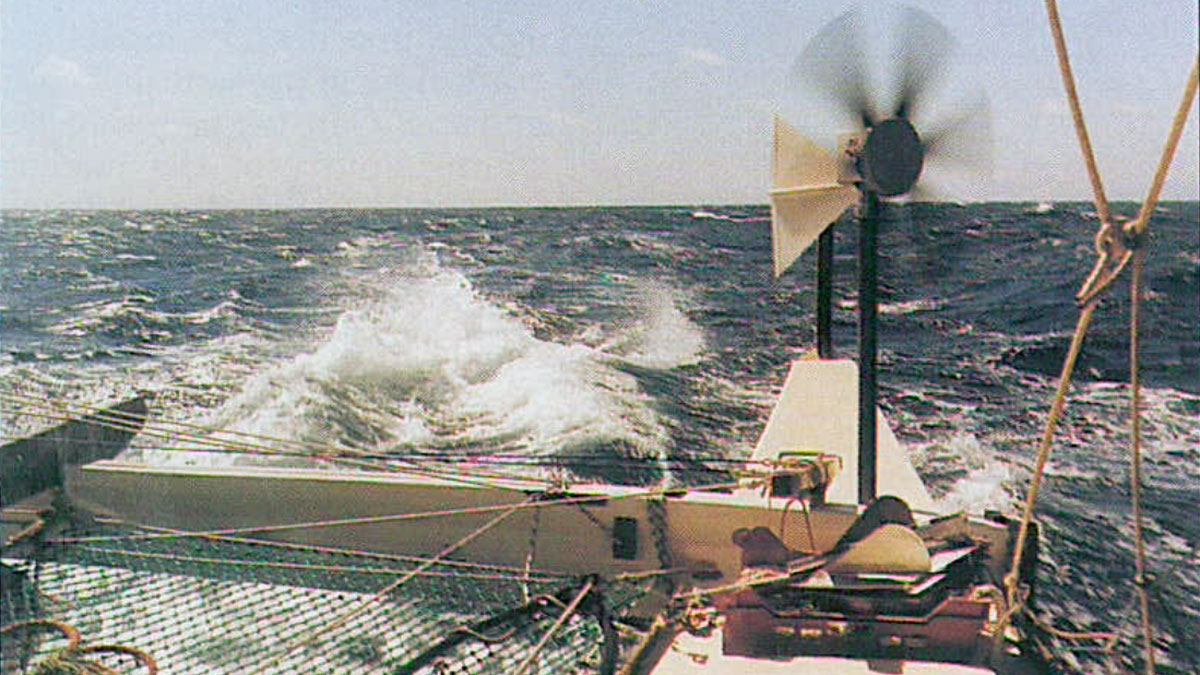

Tehini sailing from Antigua. Credit: James Wharram Archive

In 1976 they moved to a riverside property in County Wexford, Ireland, a decision that Hanneke says ‘didn’t really work out’ and began, rather inauspiciously, with them getting arrested under the Prevention of Terrorism Act.

In three or four trips they sailed their possessions 70 miles across the Irish Sea to the river Barrow to start a new life in a ‘primitive cottage’ without running water, toilet or electricity.

Here they began building two multihulls for the 1978 Round Britain. Remarkably, both boats were completed in time.

However, the 31ft proa, while very fast, flipped over during trials and didn’t make it to the start. The 35ft foam sandwich Areoi did extremely well, sailing the fastest second leg of the fleet, but blowing her genoa on the last one.

“Our sailing dreams and ambitions which had held the group together had started to sour through the constant stress and hard work,” said James, “but after the Round Britain we tried to pull together and focussed on developing our land.”

Simple construction methods are a feature of Wharram boats. Credit: James Wharram Archive

While they improved living conditions, Hanneke got to work on the new 31ft Areoi, the first commercial Pahi design.

Sadly, customers were few – the trip across the Irish Sea was too costly – and in February 1979 the postal workers went on a long drawn-out strike.

For a mail-order company this was a disaster; when the cheques arrived they were out-of-date.

A Caribbean charter project they’d commissioned for Tehini failed to get bookings and a land dispute was the final straw. The group fractured, there was a confrontation and only Ruth and Hanneke stood by James.

“People know how hard a divorce can be, but divorcing three women at once!?” said James… “It left deep emotional scars on all of us.”

In 1980, West epoxy was available to home boatbuilders. After meeting Meade Gougeon, one of the two brothers who founded the company, James decided to use it in his new designs.

The Tiki 21 was the first major design in this range, and featured their new Wharram wingsail rig.

“From these seminal designs we developed a whole range of wood epoxy designs from 17ft to 65ft, all keeping to the strict discipline of simplicity and keeping costs low,” says Hanneke Boon.

“One way of achieving this was by keeping every piece of cabinet furniture a structural strength element, saving weight and costs.”

Spirit of Gaia, here at Corfu, is a tribal boat laid out like a village round a central square, and has been sailed round the world. Credit: James Wharram Archive

In 1985 Hanneke had a son Jamie, one of the UK’s first water births, and for the next few years worked on the s.

Launched in 1992, Gaia had private double cabins or ‘cottages’ at each end of both hulls and a communal area in the middle.

The space allowed for many different crew to live, work and teach as they sailed around the world.

“It’s like a village green,” says Hanneke. “We’ve got a fire box, a hearth in the middle and a hatch we call our ‘well’ because we can get buckets of sea water from it, chuck washing-up water down, and use it as a toilet.”

At the age of seven, Jamie joined his parents on their round-the-world voyage in Spirit of Gaia, flying home for spells to attend school.

“We finished up when Jamie was 12 so he missed quite a lot of schooling,” says Hanneke. “Looking back, he said he was glad he did it but yes, it was an unusual upbringing. It wasn’t ideal but he had all these experiences of visiting all these countries. He was mainly surrounded by adults because there weren’t many children around, which may have been a bit of a handicap for him.”

James Wharram and Hanneke Boon relaxing aboard Spirit of Gaia. Credit: James Wharram Archive

She describes how in the Pacific Islands Jamie would go ashore and try to play with local children but because they couldn’t talk to each other, he’d teach them to play noughts and crosses in the sand.

“He loved swimming too,” adds Hanneke. “I did baby underwater training with him from a very early age, almost straight after birth, and so he’s always been a natural in water.”

In 1997 James, Hanneke and Jamie returned to Australia to complete the round-the-world voyage on Gaia.

Ruth, now 76, had fulfilled her dream of sailing the Pacific and decided to stay in Cornwall to run the design business, dealing with finances and organising the production and dispatch of books, study and build plans.

“Ruth was a very hard worker,” said James, “she spent many hours every day corresponding with Wharram builders and sailors, many of whom became her friends.”

Hanneke is a skilled draughtsman and has drawn most of Wharram’s designs. Credit: Hanneke Boon/James Wharram Archive

Hanneke and James overhauled Gaia in Brisbane before setting off on the 10,000-mile voyage back to the Mediterranean.

As they left the Great Barrier Reef behind, they passed a Pahi 42 and a 40ft Narai. They could hardly believe it.

“As these two 40ft Wharram catamarans swept alongside me and on to their shouted destinations, I felt a sense of awe,” recalled James.

James celebrated his 70th birthday in Ashkelon, Israel. Aware of the stresses building between Israelis and Palestinians, they decided not to leave Gaia there for too long.

After a three-month visit home to catch up with Ruth, they returned to Gaia and sailed her north-west where a new life awaited her in Corfu. “Sailing in the Mediterranean gave me a quiet inner joy,” wrote James. “I could sense history everywhere.”

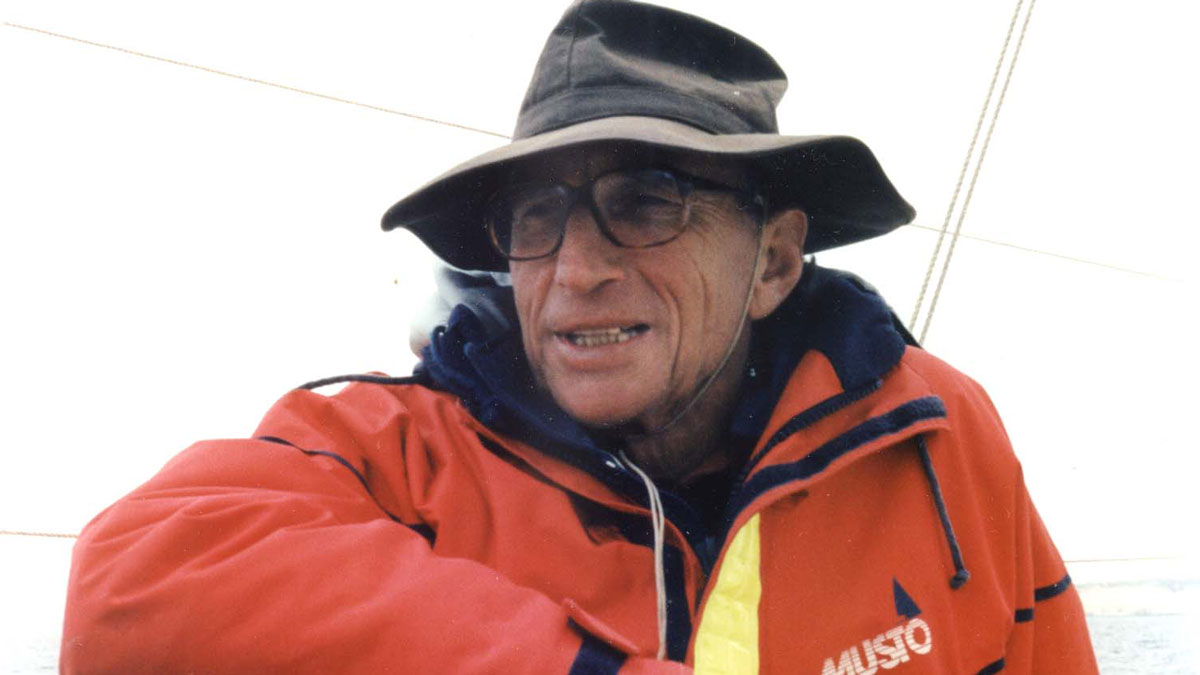

James Wharram was an innovative boatbuilder. Credit: James Wharram Archive

After six years they had completed their round-the-world voyage. Spirit of Gaia had safely taken them across three oceans, through storms and the hard sail up the Red Sea.

“What was remarkable was that we had no structural problems – nothing that we had designed and built was broken,” said James, attributing their success to the boat’s simplicity.

“No complicated systems to break down. Gaia’s simple structure of ply, epoxy, glass and rope lashings proved strong and durable.”

Leaving the boat in Greece, James and Hanneke returned to Cornwall and set about creating new designs inspired by the traditional craft they’d studied during their voyages.

The designs combined plywood hulls with solid timber beams and spars, traditional Pacific rigs and paddle steering.

They regularly returned to Spirit of Gaia to sail her around the Mediterranean where, quite by chance, they met PBO contributor Nic Compton, who in 2020 wrote a beautiful account of their round-the-world voyage.

Spirit of Gaia has no fridge or complex electronics, only GPS and a compass, and two 9.9hp outboard motors for close-quarters manoeuvres.

“I don’t really rely much on motors,” says Hanneke. “If there’s wind we sail and if there’s no wind we go slowly. When you cross the Equator and go through the doldrums there’s very little wind for several weeks. We took three weeks to sail Spirit of Gaia from Christmas Island to Sri Lanka. There were times there appeared to be no wind but we still crept along, doing 25 miles by the end of the day. Using motors is pointless on distances like that; you just have to be patient.”

Hanneke Boon led the Lapita Voyage. Credit: Hanneke Boon/James Wharram archive

She also cites the Lapita voyage, a five-month expedition she led with James and German partner Klaus Hympendahl.

In 2008 Hanneke and Klaus skippered two 38ft Ethnic Tama Moana designs 4,500 miles from the Philippines to the eastern end of the Solomon Islands. Neither carried an engine.

On arrival, they gifted the boats to the inhabitants. Having sailed since childhood, Hanneke Boom was always very capable, but for many years James was captain.

On the Lapita Voyage, it was Hanneke in charge and it was her expedition.

“James sailed on the same boat as me. We gave him the title Admiral. I mean, he was 80 at the time, so not as able. He was steering a lot, but didn’t navigate or run ashore and act all captainish!”

At the end of the voyage, James suffered a stomach complaint, which was later diagnosed as bowel cancer.

He recalled, “It was the hardest I ever sailed and physically the most strenuous. Though many of the memories of this voyage are unpleasant, I am glad I made it. With it, my life’s work of rediscovering the sailing craft of the Polynesians came full circle after 50 years.”

Cruelly, in 2011 Ruth suffered from a stroke which robbed her of her ability to read. James and Hanneke took a break from sailing to care for her until her death in 2013.

“She could no longer communicate by letter or email with her many friends,” wrote James, “to them she had been the ‘mother’ of the Wharram world. My life would not have been the same if she had not joined me in 1951 and helped me throughout our 64 years together.”

Hanneke and her all-women Gaia crew sailed to Portugal in 2023. Credit: Hanneke Boon

In 2019 Hanneke Boon married James, by which time he had sadly been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s.

Nonetheless, the couple continued sailing. “James stayed adventurous and that worked quite well,” says Hanneke. “Physically he wasn’t that bad. Even though he’d had a knee replacement he could always get into the dinghy and get on board. At home he still sat on the floor so would always be able to get up from low down.”

The Wharrams’ last cruise was in 2021, where Hanneke and James explored the Ionian with friends.

James Wharram – always the explorer and traveller. Courtesy of James Wharram Designs

“James never lost his perspective of being on the boat, but he didn’t see the logic of why we sailed in one place and he didn’t get the layout of the geography any more,” she says.

Hanneke learned to manage James’s disorientation and mood changes. The man who had been ‘too big to handle’ by a single woman was now being cared for by an exceptionally strong and determined one.

“He wanted to see the chart and where we were going and when he couldn’t grasp it; being a seafaring person, he’d get angry and we’d end up arguing.” But Hanneke persevered.

James was always a traveller and wanted to keep exploring, happy to camp and sleep in a VW transporter, which Hanneke had modified. “He called it his land yacht and we’d put James’s electric scooter in it and off we’d go. Even in Cornwall we’d go and look at the sea regularly. He was an unusual person. A lot of people retreat into themselves and fade away; James lashed out at the world.”

By December 2021, James could no longer face the prospect of ‘further disintegration’ and at the age of 93 ‘made the very hard call to end it himself’.

“It was with great courage that he lived his life and with great courage he decided it was the time to finish,” wrote Hanneke in his obituary.

Just two years before James’s death, he and Hanneke completed People of the Sea, a compelling and beautifully written account of their life and boat designs.

Shortly after James’s death, Hanneke received an invitation to cross the Atlantic with German friends on a sister ship of Spirit of Gaia.

“I thought why not? So I flew out to Lanzarote and we sailed to Guadeloupe together,” she says. At the same time, James was awarded a posthumous Lifetime Achievement Award by the Ocean Cruising Club. Could she attend the prizegiving in Annapolis?

A plan was hatched, and after arrival in Guadeloupe Hanneke flew north for the US ceremony.

Getting back on the water has helped Hanneke come to terms with James’s death. “It was good to go sailing and do some long trips again,” she says. “Being crew on the Guadeloupe trip was nice; I didn’t have the responsibility.”

The sailing also inspired Hanneke to take Spirit of Gaia back to the ocean. “She’d been in Greece for so long, and had become an Ionian waters boat so I thought Portugal would be a good place; easy to get to from Cornwall – you can fly direct.”

In Autumn 2022 Hanneke sailed Spirit of Gaia to Sicily, where the boat was overwintered. The following spring, after being antifouled with Coppercoat by a team of willing volunteers, Gaia was sailed to Ibiza where friends of Hanneke kept an eye on her.

In the autumn she made the final voyage with an all-women crew to her new home in Portugal.

Spirit of Gaia in Alvor, Portugal

Meanwhile, back in Cornwall, on a plot of land the family bought in the 1980s, the Wharram clan are hard at work.

Hanneke has a bungalow in the middle, a big workshop and a design studio. Jamie and his wife have built a house in one corner, and there are several other workers on site including their IT expert/webmaster and social media specialist.

“Business is booming,” says Hanneke. “We’re streamlining the operation by scanning all drawings onto the computer rather than feeding them through the photocopier. With social media, a lot of people can see what we’re doing. In fact, the Wharram Catamaran Facebook group has more than 11,000 members! James’s last wish was that his catamaran designs would, ‘continue to inspire and give joy to a whole host of modern sailors and travellers, while restoring credit to the ancient Polynesians’.

Clearly, he achieved this, and with Hanneke at the helm, there seems little doubt the Wharram family of self-built catamarans will live on for generations to come.

- People of the Sea is published by Lodestar Books, £16.

- Read articles, blogs, watch videos and order Wharram catamaran plans at wharram.com

- Watch the films made by Ruth of the building and sailing of Tehini on the James Wharram Designs YouTube channel.

British designer James Wharram’s round-the-world adventure on Spirit of Gaia

The morning breeze was just starting to fill in as we headed out of Port Vathi on board Ionian Spirit,…

Special Hui Gathering to celebrate the late James Wharram’s life

A celebration of the late James Wharram's life will be taking place on 22 to 25 July (exact day will…

Nomads of the wind – an article by James Wharram

In light of the recent passing of pioneering multihull designer James Wharram, we share his PBO October 1994 article, published…

Fair winds to pioneering multihull designer James Wharram

Fair winds to free-spirited sailor and pioneering multihull designer James Wharram who passed away on 14 December, at the age

Want to read more practical articles like this?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter