Bulk carrier Silver Yang took avoiding action

The 16-year-old Australian skipper, Jessica Watson, failied to spot the

bulk carrier Silver Yang on her instruments, according to a preliminary

report released by the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB).

The

collision in September delayed the start of Watson’s attempt to become

the youngest skipper to sail solo around the world, however, she has

now departed aboard Ella’s Pink Lady, her Sparkman and Stephens (S&S) 34.

The incident

At

0151½ on 9 September 2009, in a position about 15 miles east of Point

Lookout on North Stradbroke Island, Queensland, the Australian

registered, single-handed yacht Ella’s Pink Lady collided with the Hong

Kong registered bulk carrier Silver Yang.

At the time of the

collision, Silver Yang was en-route to China and travelling at a speed

of about 9 knots on a northerly heading. Ella’s Pink Lady was under

sail on a voyage from Mooloolaba, Queensland, to Sydney, New South

Wales. The yacht was making good a course of 144°(T) and a speed of

about 7 knots.

Ella’s Pink Lady was dismasted as a result of the

collision, but the skipper was able to cut the headsail free, retrieve

the damaged rigging on board and motor the damaged yacht to Southport,

Queensland.

The report in full

At about 1000

on 8 September, Ella’s Pink Lady departed from Mooloolaba, Queensland.

The skipper was intending to clear the coastline as soon as possible

and then set a course for Sydney, via Lord Howe Island. However, the

wind was only light, so the skipper was unable to clear the coast as

early as she had planned.

During the afternoon, the wind

‘glassed right out’ so the skipper started the engine and motored

Ella’s Pink Lady for several hours. By sunset, the yacht was off Cape

Moreton. The wind had freshened from the west and the yacht was again

under sail.

At about 0146, Ella’s Pink Lady’s skipper prepared

for another catnap. The yacht was making good a course of 144°(T) at a

speed of 7 knots. The skipper checked the radar and noted that there

was a vessel about 6 miles off her starboard quarter1. She could not

see it visually, but she monitored its progress on the radar for about

1 minute. Once she had determined that it did not present a collision

risk, she set the radar guard-rings, set her alarm clocks and then went

to bed again.

However, she had not detected Silver Yang, which was now about 1 mile to the south-south-east of her position

At

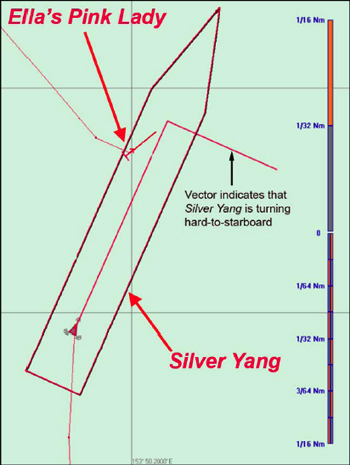

about 0125, Silver Yang’s bridge watch keeper reported observing one

green light to port, on a bearing of 345°(T) at a range of about 4

miles. He continued to monitor it and at 0148½, he altered the ship’s

heading by 10° to starboard, in an attempt to avoid Ella’s Pink Lady.

He continued to monitor the closing situation and at 0150, applied

hard-to-starboard rudder in an attempt to avoid collision.

At

0150½, Ella’s Pink Lady’s bow collided with Silver Yang’s port side mid

section. The ship had come around to a heading of 024°(T), so the

collision was almost square on (See illustration). The impact pushed

the yacht’s bow to port and its starboard side scraped along part of

the port side of the ship.

The collision woke Ella’s Pink Lady’s

skipper. She climbed out of the cabin, grabbed the tiller and tried to

steer the yacht. She looked upwards and thought that is was likely that

the yacht’s rigging would become entangled with the ship and dismast

her vessel, so she returned to the cabin. A few seconds later, the mast

came crashing down.

Immediately, following the collision, Silver Yang’s watch keeper reportedly stopped the ship’s main engine.

Once

Ella’s Pink Lady had cleared the ship’s stern, the skipper assessed the

damage to her yacht. She found no ingress of water and, although the

yacht had been dismasted, the vessel appeared to be seaworthy.

Ella’s

Pink Lady’s skipper called Silver Yang on VHF channel 16. At first,

when she did not broadcast the ship’s name, she received no reply.

She

checked the yacht’s AIS unit to determine the ship’s name, and then

called again, broadcasting using its name ‘Silver Yang’. On this

occasion, she received a reply.

It was difficult for Ella’s Pink

Lady’s skipper to understand Silver Yang’s Chinese watch keeper because

his spoken English was poor. However, over a series of short

conversations, he confirmed that Ella’s Pink Lady had been dismasted

and that neither the yacht nor its crew needed any assistance. He then

re-started the ship’s main engine, returned it to its original heading

and resumed the voyage.

Ella’s Pink Lady’s skipper used the

yacht’s satellite telephone to call her parents. She spoke to her

father and told him what had happened. While she was talking to her

father, her mother telephoned the Australian Rescue Coordination Centre

(RCC) in Canberra and reported the collision.

The ATSB investigation is ongoing and will focus on several specific areas including:

- the electronic detectability of the yacht

- the lookout being kept on board both vessels

- adherence to the International Regulations for the Prevention of Collisions at Sea (COLREGS)

- collision risk assessment

- actions taken following the collision.

Since

Silver Yang was enroute to China, ATSB investigators were unable to

attend the vessel. However, the Hong Kong Marine Department has

assisted the investigation by collecting and providing a range of

material from the ship, including statements from the master and

involved crew.

The final report is unlikely to be available for several months.