Eugénie Nottebohm sails her Contessa 32 solo to the Azores and across the Atlantic, then with crew around Cape Horn

Being diagnosed with breast cancer in 2015 felt like getting hit by a thunderbolt on a bright summer day.

After the successful treatments, I realised that I should not leave my dreams for later and bought Giulia, a Contessa 32.

At the time I was an occasional crew on my ex-boyfriend’s and friend’s boat. I enjoyed sailing so much that I took various courses at Les Glénans, a French sailing school. I wanted to be a good crew.

However, when I bought Giulia I was far from capable as a captain. I undertook a skipper’s course to fill that gap in my experience, and learned that I did not need to know everything about sailing and maintaining a yacht.

The main skill required was to make the decisions. At a personal level, it gave me a much-needed focus after chemotherapy.

Taking command of Giulia encouraged me to change my the course of my life too. Solo necessity I became a solo sailor by accident because the urge to live my new life made me impatient. I did not want to wait for crew.

I was also deterred by the mental energy crew required of me. It was easier to learn to sail on my own, pushing myself every time a little further than sailing with others.

The key was to dare just enough to safely go further.

Eugénie coming out of the Zandkreek locks with buddies in July 2017

At first, I practised with the engine, leaving and coming back to my buoy on my own, then mooring on the marina’s docks on my own.

Once I felt comfortable enough I started sailing my boat solo: first, unfurling only the genoa, then hoisting just the mainsail, and further with both sails.

I kept trying to sail longer to control my concentration level. After a few weeks, I was sailing a whole day in different conditions.

Sailing with a buddy boat was also a good way to gain confidence, progressing from a weekend sail to doing my first 500 coastal miles on my own to the north of the Netherlands.

By this time, I knew a lot of Giulia’s strengths and weaknesses, and also had a better insight into how to improve her safety for longer trips.

The improvements:

- Electrical windlass

- New batteries

- Wind vane

- Solar panels

- Inner forestay and adapted hank-on sails

- Satellite communication

Sailing offshore

Eugénie at Beachy Head, July 2018

A year later I planned a passage to Flores in the Azores to visit the friends who had supported me after cancer. It was my first offshore passage on a small sailing yacht, and solo.

I knew my boat much better to even attempt such a trip, and had improved her accordingly, but I still had to prepare myself to sail on my own far from the coast.

I did it in the same way as I started to sail solo – step by step: I first sailed longer distances, as at the time I had sailed 30 miles at most.

To reduce fatigue, I wrote down the navigation plan with all the required information: courses, navigational aids encountered, currents, description of the harbour entrances and so on.

This gave me a clearer view of what to expect, and made it easier to cope with the changes in conditions that always occur.

From Kortgene, I sailed to the Belgian coast (Zeebrugge, Nieuwpoort), further to the north of France (Dunkirk and Boulogne-Sur-Mer) and crossed the channel to Eastbourne.

I then sailed the south coast of England to Falmouth. It took me a month, by which time I had practised sailing longer distances – up to 90 miles, and also at night.

Yet once in Falmouth, going south-west would mean being on my own at sea for at least 20 days: a big jump into the unknown.

Giulia was ready, was I?

To minimise the stress, I chose a route away from the main shipping lanes to reduce the collision risks. This also meant I’d be further away from the coast.

I decided to reassess my physical and emotional situation after three days; should I feel weak I could turn east at that point, towards A Coruña, Spain. This plan made me feel much more relaxed.

Enjoying being on top of Pico Esperança (São Jorge/Azores), June 2019

Giulia in Salvador de Bahia, Brazil, January 2022

I soon discovered I felt rested by taking one-hour power naps throughout the night with five-minute breaks to check all was good on the yacht.

I also adopted one of Bernard Moitessier’s tips to create a sort of mental library of all sounds in the boat. Indeed, a sound ‘not in the library’ would automatically wake me up.

I had prepared food so as not to spend energy cooking. To address occasional seasickness, I changed the course if necessary to feel safe and take longer naps. AIS would wake me up in case a boat approached, which didn’t happen.

After a few days, I was in my element.

It was really nice to feel at one with Giulia, sailing her better each time. The company of dolphins relaxed me further.

Discovering Terceira in the early morning of my 13th day at sea gave me a real sense of how far I had come since I started to sail solo.

The joy of meeting my friends again in Flores Island in the western Azores 10 days later rewarded me for all my efforts.

This trip had also been a test to decide whether I would go further south or not. The answer was obviously yes.

From Azores, I sailed back to Portugal to haul out Giulia to check her for further passages.

From Portugal, I sailed to Madeira, the Canaries and Cape Verde. These passages went smoother each time. More confident, I enjoyed them more each time.

In Mindelo, my next challenge awaited me: a solo crossing of the Atlantic.

Transatlantic challenge

Giulia in San Julián, November 2023

Preparing myself and the boat for a three week solo passage brought quite a lot of stress. Giulia is a 32ft boat, space is a challenge. With no watermaker on board, I needed to find stowage for 120lt of water in jerrycans, 80lt of diesel in jerrycans, and the food.

The list of spares I had aboard was quite long. With a little organisation, I could arrange everything and keep some space for myself.

As in the previous voyage, I prepared soups in sterilised jars. Having soup is an advantage because you have liquid and some solids at the same time, reducing the quantity of extra water needed.

The other aspect to take care of was my psychological preparation.

Being a painter, I can spend hours contemplating the ocean but would I cope with three weeks alone?

I realised that a lot of the stress came from imagining all the possible issues and problems I could have. It was necessary to do a proper check of Giulia’s condition.

I calmed down when I realised that the likelihood that all these problems would occur at the same time was low.

My weather window arrived: wind all the way and weak doldrums. Friends gathered on the pontoon to wave me goodbye, and off I went.

Casting off for any ocean passage is always the same – you just need to slip the lines and go.

Each passage brings its new experience though. This one brought me an unforecast gale for a day and a half, 600 miles off Mindelo. Giulia and I were surfing on waves of 5m with 40 knots of wind, gusting 47 knots.

The first minutes of fear were soon transformed into adrenaline, as I thought to myself that fear would put us in danger.

I could quickly see how well-designed the Contessa 32 was. With two reefs in the mainsail and a course due downwind, Giulia surfed the waves at a speed that brought her on top of the breaking waves.

The autopilot could manage it, with me correcting the course to keep the stern parallel to the waves when one would come from the side.

Adrenaline kept me awake, sleeping respectively 30 minutes and one hour and a half, until I could relax and take my course to the south.

Luckily, I did not encounter doldrums. After 18 days at sea, I touched land in Salvador de Bahia in Brazil, quite a quick passage.

After a good rest, I pressed on to Buenos Aires, with a few stops on the Brazilian coast.

Bound for Ushuaia

Eugénie’s watercolour painting of Club Nautico de San Isidro

In Buenos Aires, I hauled Giulia out to prepare her for the stronger conditions expected in the far south. New rigging, reinforcing the bow, new sails, checking the engine, and installing a diesel heater were some of the improvements.

After three months in the yard I was off to conquer the Roaring Forties and Furious Fifties, a totally new way of sailing.

Soon I’d get used to sailing in 35 to 45 knots of wind in rough seas, and to the typical rapid wind shifts from south-south-west to north-north-west passing by west.

The mid-Atlantic gale became a dim memory. Sailing the South Atlantic solo was much more demanding as I needed to study the weather systems and cast off when the wind and waves would be the mildest.

I didn’t hesitate to wait for a month or more as I didn’t want to end up in conditions that were too strong for me.

Waiting was not a problem as the Patagonian region of Argentina offers beautiful landscapes and rich marine fauna.

I sailed solo to Ushuaia except for the legs from Camarones to Puerto Deseado, and Puerto Deseado to San Julián. I passed the Le Maire Strait and entered the Beagle Channel at dawn with a smile, so proud to have succeeded. It felt unreal.

If I had achieved that why not push myself a little more to the south and round Cape Horn?

Cape Horn

Paula, Mayra and Eugénie at Cape Horn, January 2024

In this region, the weather windows are short which means that the 200 miles from Puerto Williams are usually sailed non-stop.

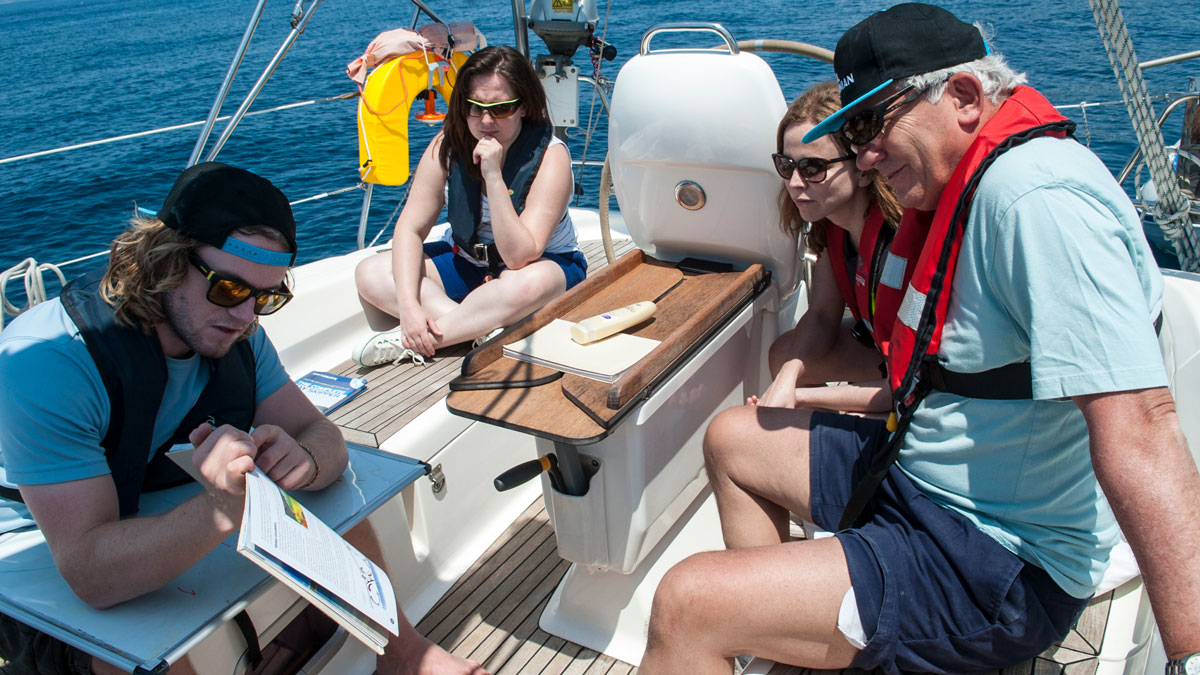

To do so I felt more comfortable having crew, it felt special to have Paula and Mayra on board as we were an all-female crew.

We had to sneak in between two depressions bringing high seas and wind and all four seasons in our leg – sun, rain, hail and snow, from no wind to 45 knots, from all directions.

But the atmosphere was very good on board. For the last few miles Giulia was caught in mist, the landscape enveloped in mystery.

We even wondered if we’d see Cape Horn at all. But just as we turned south of the rock the mist dissolved.

Everyone on deck was in awe, the rock shone into the dim light, waves hitting her feet, a colourful sculpture.

Once there I felt what a milestone in my sailing life it is to have brought my 32ft sailing yacht, my beloved Giulia to the southernmost cape of the Americas.

Knowledge gained from sailing to the Azores and beyond

My notebook, August 2017

Which chart did I use?

I like to have paper and electronic charts. The paper ones were from Imray and Admiralty.

For the electronic ones, I chose Navionics on an iPad. Only in Patagonia were the Navionics charts not precise enough to follow the coast – switching to ‘satellite view’ addressed this problem.

I have no chart plotter on board, just a GPS. I do the routing myself.

To prepare I consult the usual pilots, but also talk to as many sailors as I can, and local fishermen who know the seas very well and are happy to share their knowledge.

I write down in my notebook all comments and the route with waypoints, potential dangers and navigational aids, visualising the trip helps me to cope with bad weather as I know what I am looking for.

While navigating I plot my position on the paper chart every hour on short passages and every three hours on a long one. This discipline allows me to focus on the navigation and, combined with checking my written notebook, I can anticipate the trickier stretches of the passage.

I have also learned to better observe changes in conditions, eg seamounts will bring choppier seas, local effects due to the geography. And if conditions worsened I could give my approximate position should I need help.

Crossing the equator in the South Atlantic, Christmas eve 2021

Weather forecasting

When I started I had an Iridium satellite phone, and downloaded GRIB files through my computer. I changed that system because it didn’t work out smoothly on my Mac. It took too much time which was not easy when I was tired.

I then had a friend send me weather forecasts through text messages, in the morning and in the evening. He had access to more precise data. I could also ask him questions when the conditions I had didn’t match the forecast I’d received.

Over time we worked out a good system, but it was quite demanding for him so I then switched to an Iridium GO! using PredictWind.

This turned out to be a good solution once in the South Atlantic because I could better visualise the weather system and adapt my route accordingly.

In this region, the weather changes abruptly and quickly. The forecast is usually correct for a day or two. This was a problem between Florianópolis and Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil and along Argentina’s Patagonian coast because there are few safe places to stop and some legs are four days long.

To address this issue I’d start analysing the weather forecast days before the date of departure to try to understand the dynamics.

After a while, I concluded it was better to cast off with a weak south wind even if I had to beat windwards to catch as much north wind as possible once at sea.

The rule of 50% engine use and 50% sailing did apply to me. I’d also anticipate the wind shift, opening sometimes the course to the south-east to be able to continue south-west with south wind and still be far enough off the coast.

With each leg, I’d gain a better knowledge of the weather which helped me to cast off with better conditions for the subsequent leg.

Along the South American coast, the GFS model proved to be the most accurate about the wind direction and strength. However, as a rule of thumb, I’d plan for the strength of the gusts as the expected wind strength. This was mostly correct.

Once along the coast of Tierra del Fuego, the ECWF model was more accurate, with the same rule taking account of the gusts as the established wind.

The actual route

In my experience, the passages from continental Portugal to Cabo Verde were quite straightforward as the northerlies and then the north-easterlies pushed Giulia to the south.

The question was to wait for the right moment. Except for the gale, the passage from Mindelo to Salvador de Bahia went smoothly. I only had to motor 10 hours on an 18-day passage.

The wind did the rest. It became more demanding once in Salvador de Bahia, until Cape Horn. I also had to cope with thunderstorms, the most impressive being in Rio Grande do Sul.

Fishermen’s nets are also a challenge, mostly along the Brazilian coast where they are poorly lit.

Finally, it’s worth noting that regular quick windshifts in the South Atlantic create confused seas.

First-time boat skipper: tips for your first voyage in charge

Skippering a yacht for the first time is a pivotal experience; one that's rewarding if done right. Rupert Holmes explains…

Contessa 32: the second-hand classic + 6 alternative boats

Rupert Holmes analyses this extremely seaworthy classic and suggests a dozen other viable lower-cost alternatives

How to go sailing and boating if you don’t own a boat

From tall ships to small dinghies, you don't need to own a boat to go sailing. Ali Wood looks at…