A performance weekender built in Britain has been missing for a long time – which is why it’s good to meet the BTC-22, says David Harding

Let’s say you’re looking for a trailable cruiser of a sporty disposition and around 22ft in length. You acknowledge that some of the traditionally-flavoured designs of recent years can sail very nicely, but you’re not interested in bowsprits, gaffs and low-CE rigs.

In fact none of the trad-style features and accoutrements really appeal to you because, pleasing though they are in their own way, they involve compromises when it comes to performance.

What you want is a boat that maximises sailing efficiency through an unashamedly modern approach, combining a light, easily-driven hull with a high-aspect ratio rig and a low-CG keel.

Boats like this can reach double-figure speeds downwind without breaking sweat and are fast even when driven at half-throttle.

If you get keen and choose to open them up – well, they have the potential to go pretty rapidly while still being much less demanding to sail than a fully-blown sportsboat.

Unless you’re set on the trad and tan, boats like this have a lot to offer.

The problem is that few builders are producing small sporty cruisers any more. Back in the days when Britain had what could be described as a yacht-building industry there were dozens to choose from.

Since then we have been largely dependent on imports from European yards, but recently they have been abandoning small boats too.

Over the past few years Beneteau has discontinued the First 20 (which started life many moons ago as the First 210), the Sun 2000 was the last boat of this size from Jeanneau way back when, and Elan has dropped the likeable little 210 (tested in PBO July 2012).

Plenty of low-down ballast makes the BTC a powerful performer to windward. Credit: David Harding

European lake-sailers are plentiful, though mostly without representation in the UK, and all too often they’re not the sort of boats you would choose to sail in our coastal waters anyway.

The same goes for many of the Polish offerings that became popular in the early 2000s before largely disappearing from the scene over here.

Among the few to choose from are the Seascape 18 and 24 (tested in PBO Summer 2011 and August 2017 respectively, thoroughly well thought out and now sold under the Beneteau umbrella).

You can still find trailable performance cruisers in France, Holland and the near continent, but not everyone wants to go to the trouble of finding and importing a boat that’s likely to remain the only one of its kind in the country.

Besides, what about buying British? We can build big powerboats and we also make plenty of hardware for yachts that we sell to the French and Germans so they can bolt it to their decks and sell it back to us.

With a few notable exceptions on the sailing-boat front, however, (the Hawk 20 being about the only one that’s small and remotely sporty), that’s pretty well it.

What we’ve needed for years is for a British builder to introduce a sporty 22 – the modern equivalent of boats like the Evolution 22, Anderson 22, Caravela 22, Limbo 6.6, Skipper 700 and others that introduced so many people to the pleasures of sailing lively little trailable cruisers.

Accommodation is light, bright and simple. A trailer winch lifts the daggerboard and the case will be of broadly similar proportions with the centreplate, which swings up beneath the hull. Credit: David Harding

Seeing the light

Thankfully that’s exactly what Composite Mouldings in Southampton has done. Composite Mouldings (CML) makes all sorts of – surprise, surprise – composite mouldings for yachts such as Oysters, as well as building pilot boats and producing mouldings for industrial applications.

CML was born out of Blondecell (think Cromarty 36, the Tradewind range et al) and has built nearly 400 Hawk 20s for Reid Marine.

So although its name might be unfamiliar in recreational boating circles, the company has a long-standing association with boats we’ve all known for decades.

CML is headed by Warwick Buckley, who is also one half of Buckley Yacht Design with his son, Jami.

Between them on their CVs they include being part of the crew on Flyer, winner of the Whitbread Round-the-World race in 1981-82, and working on the design of Alex Thompson’s Hugo Boss.

With this experience to draw upon, plus a yard that’s well versed in resin infusion, structural analysis and the use of carbon fibre and aramids, the design and production of a 22ft trailable cruiser should be well with CML’s capabilities.

We first reported briefly on the RTC-22 (as she was then known) in PBO January 2016. At the time she had only recently been launched and was still a long way from being sorted, so we accepted that we had perhaps jumped the gun.

Nonetheless, I for one thought this was a boat that people should know about.

She was going to be developed over the following few years and I didn’t want to wait that long to let the world (or at least the enlightened part of the world that reads PBO) know about her.

Double guard wires are a welcome and unusual feature on a boat of this size. Credit: David Harding

Several years have now followed and, by accident rather than design, I saw the BTC-22 at the Southampton Boat Show.

She was being shown by Boatwork, who have joined forces with CML on the sales and demonstration side to promote the boat from a base in the midlands.

Before she disappeared inland I took the chance to have another sail on salt water with Warwick Buckley.

On the day we chose, however, we found ourselves facing one of those ‘get yourself out of here!’ challenges before we could go anywhere.

The boat was berthed on the inside of a pontoon next to a muddy river bank.

We had no way out forwards because of the walkway ashore and we also had the combined forces of a spring ebb and brisk northerly breeze up our stern pinning us in.

To add to the fun there was no outboard motor.

After a little lateral thinking and fore-and-aft manoeuvring – lateral manoeuvring not being a good idea in those conditions – we got ourselves out and set off down the river.

As I remembered from our previous sail, the BTC was a sprightly performer. She accelerated rapidly in the gusts, responded instantly to every twitch of the helm, went through the wind cleanly and precisely and was soon back up to speed after a tack.

Short-tacking down (or up) a tree-lined river with gusty, shifty winds is always a good test of a boat’s handling qualities and the BTC passed with flying colours.

One feature that makes sailing easier is a deck layout that allows for straightforward cross-winching of the jib.

It’s such a simple and sensible idea, especially on a boat of this size where crew weight makes an appreciable difference.

While aspects of the rig and hardware still needed sorting – we’ll touch on those in a moment – the boat was transformed from the way she had been three years ago by the redesigned steering.

On our first sail she had been a serious challenge to manage because the blades of the twin rudders had no balance and the tillers were barely 18in (46cm) long.

This combination led to a weight on the helm that was impossible to hold at times.

Since the discussions that followed our sail, the hinge-up blades have been given some balance and the steering mechanism has been revised.

Whereas initially the two short (and too-short) tillers were simply joined by a link arm to which the tiller extension was fitted, the arm is now driven by a central pivoting tiller.

The result is steering that’s agreeably light so you can concentrate on sailing and enjoying the boat.

Fast fun

There’s much to enjoy with the BTC (which, incidentally, stands for Buckley Trailer Cruiser – no one was sure where the initial designation of ‘RTC’ came from).

Once out into the Solent we had conditions that were nigh-on perfect for letting her show what she could do: the water was almost flat and the breeze between 12 and 20 knots.

Upwind she clocked around 5.5 knots and settled into an easy groove, being far from twitchy but making it clear when you hit the sweet spot.

This is a boat that ‘won’t frighten Granny’, as the late David Thomas would have said, yet at the same time she rewards careful trim and concentration.

Offwind she gets up and goes, sliding along at an effortless 7-8 knots in any breeze if you keep the angle reasonably hot.

At one point late in our sail, as we were heading back towards the river and thinking we were going home, the wind picked up to the high teens and stayed there for a good 10 minutes.

Even under plain sail – sadly the test boat had not been equipped with a spinnaker – she picked up her skirts and flew along on an effortless semi-plane at close to 9 knots.

Downwind sails will typically be in the form of asymmetrics because the BTC is fast enough to gybe the angles.

On the other hand, a symmetrical spinnaker often works best for club racing in tidal areas.

This is one of many choices available to owners: CML will offer a higher degree of customisation than most builders of boats this size.

BTC-22 interior plan view

For all her speed and responsiveness, there’s still a great deal more to come from this slippery little ship.

For example, changes to the mast step on the test boat had left the rigging too long, so although we tensioned it as far as possible before setting off we were left with a good deal of forestay sag and the leeward cap shroud waving around in the breeze.

Things needed tightening up in the steering department, too: there was play between the rudder blades and the stocks and between the tiller and the link arm.

The cranked tiller itself is substantial and rather higher than I would have liked.

This is to provide easy access to the locker underneath it in the cockpit sole, where an outboard can live.

Alternatively, and preferably in terms of weight distribution, it could be stowed beneath the bridgedeck.

Still on the subject of things that flopped around, we felt the inertia of the daggerboard coming up against the forward end of the case when we bounced over the odd wave.

It’s something you experience occasionally on boats with daggerboards like this and probably nothing to be concerned about.

All the same, it’s preferable if a lifting keel doesn’t remind you that it’s there until you want to lift it. Boats like this feel so much better when they’re crisp and taut.

Staying with the foils, profiling the rudder blades all the way up to the stock where they have been modified to create the balancing area would help: at the moment the section above the bottom of the hull presents a square leading edge.

The boat herself is anything but square. It would be easy to look at her and imagine that, with her light weight, generous sail plan and high aspect-ratio keel, she might be a handful when the breeze picks up.

Even 20 knots is enough to show up any twitchiness in a 22-footer, but this one demonstrated that she’s remarkably tolerant and forgiving.

If sailed too deep on the wind with the main pinned in during the strongest gust we could find, she rounded up gently only when on her ear and with the leeward rudder blade at such an angle that it could no longer be expected to work.

Up to that point, the generous area of the blades (they’re big for twin rudders) provided a tenacious grip.

We could pinch mercilessly upwind while maintaining steerageway down to less than 2 knots of boat-speed.

If we spun tightly through 360° from hard on the wind, she crabbed with the foils stalled for a few seconds before laminar flow was restored and off she went again.

All told she was hard to upset.

Details of the deck layout have yet to be finalised but fundamentally it’s functional. Cross-winching the jib sheets works well in a breeze. Credit David Harding

Maximising performance

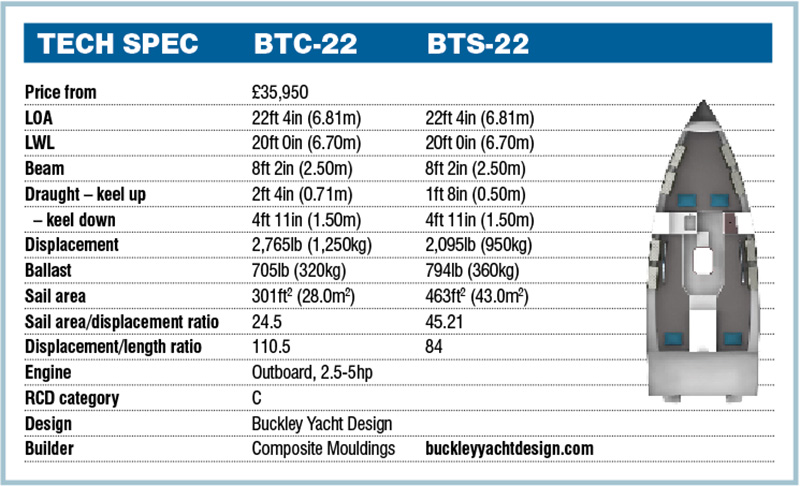

Those wanting more of an adrenaline surge when the boat enters full production will choose the souped-up BTS-22 version as opposed to the BTC.

The BTS-22 will have the T-bulb daggerboard as on our hybrid test boat, paired with a fat-head mainsail to give her 160ft2 (15m2) more sail than the BTC.

Weighing 2,100lb (950kg) she will also be 660lb (300kg) lighter thanks to a more basic interior and the use of carbon fibre in the structure.

It’s a combination that should make her a pretty potent performer.

With an emphasis more on family-friendliness, the BTC will be given a centreplate (with the same draught as the daggerboard’s) that swings up beneath the hull.

On both models the freeboard will be 2in (5cm) more than on the test boat and the cockpit longer – by about 4in (10cm) on the BTC and 18in (46cm) on the BTS.

Construction will be in resin-infused composites with a foam core for minimum weight and maximum stiffness.

As on the prototype, the rigging, hardware and fittings will come from well-known names including Z Spars, Spinlock and Harken.

Features on deck worthy of comment include the double guardwires. They make such a difference when you’re hiking on the rail.

Sonata sailors always look so uncomfortable with the single guardwire too high to allow them to get their weight outboard.

Aspects of the hardware and deck layout still need refining, which will happen when the marketing and production get into full swing.

It’s more than three years since the boat was first launched because the development has been a sideline job for CML.

That’s a far healthier state of affairs than if a project of this nature were being relied upon to sustain a business: we’ve seen too many boats arrive in a blaze of publicity only to disappear a year or two later because the figures didn’t stack up.

Despite the low-key approach thus far, BTCs have been sold and it seems almost inevitable that a meaningful number will find homes with appreciative owners who have been wanting a boat like this.

Structural design looks reassuring throughout. This is the sheave for

the daggerboard’s lifting cable. Credit: David Harding

Accommodation

Below decks is a surprising amount of space, which will be increased vertically and reduced fore-and-aft on production boats by the higher freeboard and shorter coachroof.

As it is, headroom is a more-than-adequate 4ft 7in (1.40m) in total and just over 3ft (0.92m) above the bunks.

All the berths are a generous length – the V-berth in the bow is 6ft 6in (1.98m) and the settee berths will accommodate anyone up to 8ft 3in (2.51m).

The photos tell the rest of the story. The finish is light, bright and simple with a minimal but effective amount of timber trim.

PBO’s verdict

If ever a boat filled a gap in the market, it’s the BTC-22.

With so many builders continuing to move up the size range and 40-plus footers now being described as ‘starter boats’, there has been an increasing need for lively and well-mannered trailable cruisers that, like the BTC and BTS, fit between the full-on sportsboats and semi-trad modern classics.

The BTC’s birth has been slow, and detailed refinement is still needed before her full potential is realised.

Given her pedigree, however, this should just be a matter of routine: it looks as though a British-built sporty trailable cruiser will soon be making its presence felt.

And not before time.