With a summer holiday being firmly rooted in the French canals, Richard Hare agreed to have the family cat aboard. The plan cost less than keeping Polly in a cattery – but it was far from plain sailing

‘We’ve lost her. She’s gone. I’ll never see her again.’ My wife Janie’s bottom lip quivered and tears welled in her eyes, writes Richard Hare.

‘We should never have put her in a harness – she’s not used to it and she’ll end up hanging herself from a tree,’ she blurted. The spectre of failure loomed over

us like a heavy wet blanket.

Darkness had fallen and Keppel had settled on the ooze, tied to the pontoon in the Gironde estuary where she had over-wintered. To accustom our cat Polly to yet another lifestyle change we’d put her on a harness and lead that evening.

Relaxed and relieved at being back in the water without mishaps, and mellowed by wine and a good dinner, my grip on the lead was not all that it might have been.

Quick as a flash, Polly hopped over the guardrail, harness, lead and all. Being a healthy 10-year-old, used to wandering the boatyards at home, it was a natural enough thing for her to do.

I lunged over the rail in a bid to grab the lead, landing heavily on the squeaky pontoon. It was a stupid thing to do because the signals I sent were negative – I appeared angry and she felt she’d been naughty.

Worse still, she’d not had any time to ‘clock’ her surroundings or even gain a glimpse of what Keppel, her new home, looked like from the outside.

She shot down the pontoon, her cinnamon hindquarters disappearing into the darkness, her lead clattering along the boards behind her.

And then there was silence.

By the time we reached the end of the pontoon she’d vanished, leaving only a dent in the ooze where she’d landed. A few strokes indicated that she might have clawed her way to the steep reedy bank that led up into the boatyard.

We called out but there was no reply.

Janie suggested that I return to finish the washing-up while she resigned herself to a night at the top of the ladder, in the hope that Polly would return.

After 45 minutes she did, but looking more like a choc-ice than a cool cat – terrified, and minus her harness and collar.

We lowered her down the ladder to the pontoon, scared stiff she’d freak again and repeat the scenario. She made a beeline straight for the security of the forecabin.

That night she slept on top of Janie, still muddy (not wishing to upset her further we hadn’t attempted to clean her up), and she didn’t budge an inch.

Next day Polly was so crunchy she could hardly walk. She minced stiff-legged around the cabin and there was nothing for it but a scrub in the bucket. It was further insult and she complained bitterly.

It was dawning on me that bringing the moggie along might not have been one of our brightest ideas…

Car journey and camping

The car was prepared for all eventualities

Our passage plan for the summer was to explore the Gironde estuary and take Keppel up to Montauban, a fortified medieval ‘bastide’ town up on the Toulousian plain. First, though, we had to drive to the boat’s base at Mortagne-sur-Gironde.

En route we camped at Bonneval, a delightful little town roughly half way.

Having prepared the car to make it cat-friendly – an open cat basket for safe haven, an area for food and water, and the all-important litter tray – Polly had a little ‘accident’ within five minutes of leaving home.

The sight of the world whizzing past at 70mph was sufficient shock to her system that she ‘forgot’ herself. To put this into perspective, she had never been

similarly caught short before.

No matter, it was our fault for not anticipating this. She settled down eventually, after making some bitter demands for her world to slow down, all of which were ignored.

On arrival at our son’s house in Canterbury she was based, litter-tray and all, in our bedroom, safely away from our daughter-in-law Sarah’s moggie, Harold – Sarah was convinced they’d have a punch-up.

Polly en voiture, free to roam in the back of the car while under way

Next day we boarded the ferry at Dover, leaving Polly on her own inside the car.

Being adjacent to the stairwell up to the passenger decks, drivers were fascinated by the wide-eyed creature in our rear window, so we stayed until everyone had gone upstairs before bidding our own farewells.

On arrival at Dunkerque we scurried anxiously back to the car to find her indifferent to our return. Good news: the calm crossing obviously hadn’t distressed her. Left alone with strange noises it’s easy to understand how a rough passage could frighten pets down on the car deck.

On the way to Bonneval we stopped for lunch in one of the picnic lay-bys but she didn’t want to leave the car. Every rustle and movement scared her and the

constant roar of traffic didn’t help.

That evening she had two hurdles to overcome: first, the tent and, secondly, a night alone in the car.

A walk on the lead around the unfamiliar campsite was plainly not going to be top of our list of things to do, so we attached her lead to a table leg and let her doze while we busied ourselves with the shower block and supper.

Having never been on a lead in her life she panicked and got herself all knotted up around the table legs. Things weren’t getting any better.

She was happy enough sleeping in the car though. Janie draped a towel over her basket to add warmth and privacy and her food and toilet was there to use as and when.

In the morning she seemed relaxed and secure so was allowed back in the tent for morning cups of tea in bed. With routines beginning to re-emerge we were able to maintain some familiar landmarks.

Launch day in Mortagne. It has to be high springs even with a 1.2m draught

On arrival at Mortagne we based ourselves at the excellent little Camping Municipale while we got on with some of the more disruptive fitting-out jobs.

It didn’t work well with Polly because it confused her. Which was home – the boat or the campsite? There was a scary incident too. While Janie took her for a walk on her lead around the site one evening Polly smelt a dog, panicked, escaped her harness, and was only just grabbed before she shot off into the undergrowth outside the campsite.

Yet again, it was something that we hadn’t given thought to. Although she

was fine being left in the car after the sun had set, giving us the chance to pop down to the harbour for evening meals, the campsite idea wasn’t working out well so we upped tent pegs and relocated to the boatyard to live onboard – something we should have done in the first place.

Hang on a tick

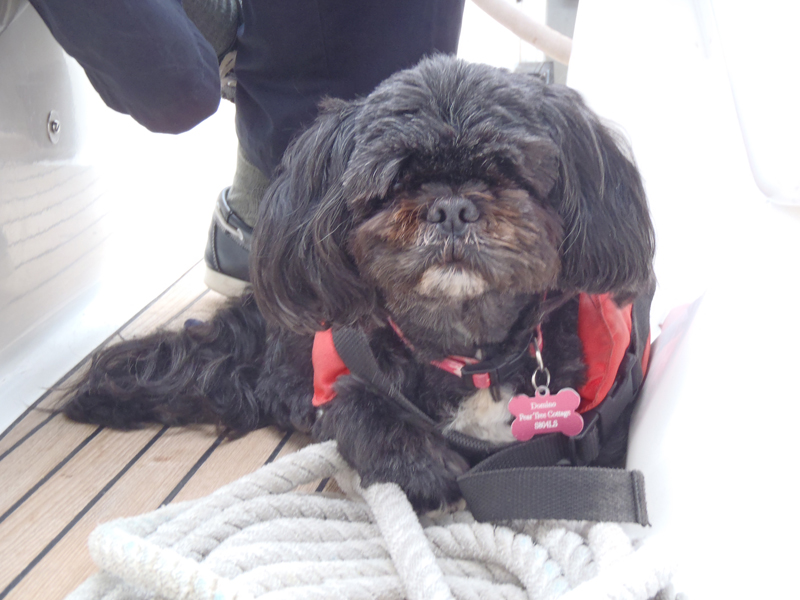

Watching the world go by, our curious cat on the canal

Shortly after relocating to the hardstanding Polly found that she had a new chum. Janie had noticed her pulling at her fur and picking a tuft off the floor

found a tick within, its head buried deep in a tiny piece of skin, its blood-bloated, 6mm body pulsating. It was truly disgusting. (The Charente region is well known for them, we later learned.)

Fortunately, Polly had tugged the head out along with the tuft. Janie knows from

her Queensland childhood that, had she not done so, all sorts of expensive complications might have followed. Ticks must never be pulled out if there’s a chance of leaving the head buried. Polly was fortunate this hadn’t happened.

So was our bank balance. No longer would I question the legal requirement for tick vaccinations in France before returning to the UK.

An old Australian remedy for ticks is to pour kerosene over the affected area. It

encourages the tick to extract its head and drop off. However, my new chum in the boatyard – Mike, a British resident – convinced me that as a prevention to getting ticks in the first place Frontline Spot On (good against fleas too) was the best available. He uses it on his dogs. The fluid is applied directly to the skin at the back of the neck, from where it migrates to the rest of the body.

Available from vets and pharmacies both in the UK and France (and also from the French garden centre chain Art Vert), it’s expensive, but it works.

Living on the hardstanding

Keppel on Mortagne hardstanding, with the ladder angled anti-cat

The boatyard was fine for 14 days. Keppel’s decks were too high for Polly to jump down, and our ladder was set so that she didn’t want to use it, so she remained on board, roaming free sans harness.

We locked her below when we were away, hatches left ajar and small windows open. She adjusted to this lifestyle easily.

Plainly, a 31-footer offers more space than a cattery pen, but given that she wanders across the railway track into the boatyards at home her lack of interest in exploring unfamiliar territory was surprising.

Her litter tray was moved inside and out and she was happy to use it at night, albeit making a hell of racket in the process.

Living on the water

Our first few minutes out in the estuary were inauspicious – Polly threw up.

There was a slight swell as the Atlantic poured into the estuary but it wasn’t even rough.

As we moved up the estuary it became narrower, more settled. Polly had no more seasickness problems until two months later, when we had a bumpy crossing of the mouth of the Gironde – but then she wasn’t the only one who felt a bit green.

On the open estuary our worry became the very fast tides. Everything that falls overboard is whipped away in seconds and no-one attempts to swim against it.

Our rule was that if anyone fell overboard while we were moored or at anchor they were to swim unhurriedly shoreward and crawl ashore where the tide deposits them. Boatscan then be anchored off and castaways recovered.

But try explaining that to a cat.

So, on tidal waters, she was always in harness and ‘on lead’ except when she was confined below. We added more line so she could roam out into the cockpit but if she was settled below we slipped the lead off the galley tap altogether.

She accepted this without any fuss or complaint.

On entering the canals many of our anxieties fell away. We left the lead off except in the locks. If she fell into the canal, she would swim easily to the bank.

Failing that, I’d jump in and retrieve her.

But this regime only worked up to a point. When we allowed Polly to roam ashore in the evening it became too much for us. Know how it feels when you have an animal whose first instinct is to disappear down each and every hole it discovers?

This was invariably the first thing Polly did when she jumped ashore.

I didn’t want her terrorising mother ducks with their flotillas of chicks either.

Amusingly, magpies chased her back on board more than once and one scrawny individual had the audacity to peck her bottom all the way. There’s not much dignity for a cat in that.

But about 10 days into the canal, at Moissac, we hit our crisis. We’d had enough and clearly hadn’t thought it through properly. We’d have to keep her on a lead hereon, or pack up and go home.

Interestingly, on that night her behaviour changed and she became cowering and

defensive in our presence. In over 10 years she’s never behaved like this.

Plainly, she was distressed because she sensed there was something wrong with us.

As soon as we had our own thoughts back in order we had, in her eyes, taken back control. This is what our pets want from us and she relaxed instantly.

We opted to continue our journey but stopped the night-time rambles – it worked.

Polly made herself at home on the French canal banks

In the drink

The only other time Polly fell in was when we were moored at Valence d’Agen, a canal town. She seemed interested in the rickety, unoccupied boat adjacent, but Janie didn’t want her hopping across as it had many open windows.

As Polly sprang, Janie tried to prevent her but this served only to break her trajectory – she plunged into the canal.

She popped up like cork and swam impressively to the bank, then scurried under a nearby camper van to recover her composure.

Although she seemed to enjoy the cooling dip, she never showed an inclination for a repeat performance.

But we didn’t always have her in harness on the canal. If she was settled and not

over-curious about something ashore (and always at bedtime) we left her out of it, but we constantly had to keep an eye on her.

Cool for cats

In the cool of the evening, an even cooler cat

France in 2009 saw temperatures of 40°C.

Cats cope with high temperatures, but the airless heat of southern French waterways in a notoriously hot summer cannot be compared with, say, Greece,

where there’s nearly always a good breeze.

In the canals, even the bimini gets hot, slow-cooking those taking shelter beneath.

Polly coped by staying in the shade, usually below decks. She’d find a draughty

spot on the cool floorboards to splay out – while motoring, the forehatch funnelled in a steady breeze.

Occasionally she’d come out into the cockpit but only if there was both shade and breeze. She avoided sunlight like the plague, but she liked to join us in the cockpit at dusk.

Central square, Montauban – but, with no shade, how hot was it for Polly back aboard Keppel?

Was it worth it?

By taking Polly with us we saved quite a lot of money, but whether that makes it worth it is another matter.

It’s easy to forget that our pets are going to have their worlds and routines turned upside down and there’s nothing we can do to forewarn them or reassure them that it’s temporary.

Given this, Polly’s conduct was exemplary and she dealt with the changes in her own way. Our role was to reassure her that she was doing fine. It was only when we interfered that things went awry.

We didn’t cope well with the thought of losing her, and felt guilty about leaving her in a hot cabin too, albeit with plenty of ventilation. The problem was always with us, not the cat.

For me, being aboard Keppel for a few months is to step sideways into an alternative existence. I don’t take a computer and I don’t do internet cafés. I leave all this behind, and I shouldn’t have taken a cat either.

For me, severance from my daily routines is part and parcel of the refreshment of being on board. The year we took Polly along – bless her – I blurred the lines. And as for Polly, she seemed very happy to be back home.

FINDING A FRENCH VET

The French vet’s

This is best done before UK departure.

Contact the French Embassy in London for details of veterinary surgeries in the town you want to use. We selected Etaples and Montreuil as they’re in striking distance of all channel ports, and nice places to boot.

I wrote a letter because an email-address wasn’t supplied, plus letters usually draw a better response than phoning. Dialogue thereafter was electronic.

■ Contact: The French Embassy, 58 Knightsbridge, London, SW1X 7JT.

www.ambafrance-uk.org/-Importing-animals-into-France-

Good general information about taking a pet to mainland Europe and back can be found on the DEFRA website, www.gov.uk/take-pet-abroad

Check ‘animal health and welfare, bringing pets to the UK.’

TRAVELS WITH A PET: THE FORMALITIES

For journeys to and from the vet, a cat basket is the sensible solution

- Taking a pet across to mainland Europe is a long-winded process involving formalities, vet visits, costs and up to six months’ planning:

First, a visit to a UK vet who inserted an identity microchip into Polly’s neck and administered a rabies vaccination. - One month (minimum) later a second visit to the vet, to take blood to check the rabies jab. Chip also checked.

- Another month later, chip checked again, learned results of blood test. Polly ‘passed’, meaning she could either:

a) Leave for continental Europe in six months’ time with an immediate return allowed, or…

b) … she could leave immediately after publication of the test results but not be allowed to return to the UK until six months after the vaccination.

A smart new pet passport was issued so off we went on Polly’s continental Grand Tour. - At the end of her time abroad Polly went again to a vet’s, this time at Etaples, near Boulogne. The vet gave the mandatory tapeworm and ticks vaccination, and zapped Polly’s ID chip too.

This jab, administered and registered professionally, is essential for a pet to return to the UK. The owner-administration of proprietary tick treatments does not count. If the animal takes tablets without a fuss the

treatment can be administered orally, but Polly did it the hard way. - The timing of the return ferry to the UK must commence in France 24-48 hours after French vet treatment. It pays to check that the vet logs the vaccination time in the passport exactly, not rounds it up – Polly’s jab was at 1550 but the vet logged it at 1600, so we didn’t qualify for the 1600 sailing the next day and had to wait a further two hours.

From the computerised ticket, the French-side check-in staff knew that we had a pet on board and Polly’s passport was checked for verification of her medication.

We didn’t have to present her for inspection any more. Satisfied that all was in order, we were issued with a sticker by French passport control that we had to display on the car windscreen for the benefit of the

authorities. We were told not to remove it until we had departed Dover port.

At passport control on the French side the officer also checked that Polly was on board.

Meanwhile, British passport control (French side of Channel) also asked for her passport.

We were not stopped in Dover, the sticker was Polly’s ‘green light’ to hurry home.

Cost of taking a cat across the Channel

■ chip insertion and the rabies vaccination: £67

■ blood test to check rabies jab: £46

■ optional sedation for blood test: .£14

■ issue of passport: £43

■ additional ferry charges (Norfolk Line, Dover/Dunkerque): £30

■ tick and flea vaccination in France: £30

■ cat food while away (£20/month): £55

TOTAL: £285

Typical cost at a cattery: 2.75 months @ £200/month £550

Saving made by taking Polly abroad £265

NB Subsequent years yield extra savings of more than £100 as there’s no chip insertion, blood test or passport fees. This assumes re-vaccination occurs within 12 months of the previous one.

As published in the September 2010 issue of PBO. For more useful archive articles explore the PBO copy shop.

PBO Seadogs (and other sailing pets)

Contact us and Send us your seadog photos for our web gallery and your pet may be lucky enough to…

Final preparations under way for ARC 2015

Excitement is building and tensions are high as final preparations get under way in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria for…

Rescued yachtsman reunited with his sailing cat

A yachtsman and his cat who were rescued off the West Australian coast by a container ship have been reunited…

Rescued cat-carrying French yachtsman is fundraising for a new boat

Solo sailor Emmanuel Wattecamps dramatic leap to safety with his pet cat from his stricken yacht was captured on video.

How to catch fish while sailing

Catching supper with hook and line is a pastime most yachtsmen will attempt at some time or other, but why…

Sailors’ pets cut adrift

Bringing pets back home from Europe becomes more difficult for yachtsmen