Frank Cowper published the first amateur cruising guides 120 years ago. Ben Meakins reads Cowper’s Sailing Tours and plans his own passage, reflecting on sailing then and now

Maybe I’ve read too many classics of sailing literature, but I sometimes find myself yearning for the leaky wooden yachts, seat-of-the-pants navigation and quiet solitude of cruising in the early 20th century. Then I look round at today’s fast, snug, weatherly yachts and pinpoint satellite navigation and I’m not so sure.

Nostalgia ain’t what it used to be.

I blame the writing of Frank Cowper. You could say that he was the man who started the cruising lark as we know it. He was one of the few amateur sailors who, in an age when any self-respecting yachtsman had a full paid crew to do the sailing for them, cruised his heavy yachts single-handed around the coasts of the UK and Northern France from the 1870s.

Frank Cowper’s Sailing Tours were published in five volumes – an original set can fetch as much as £500

His cruising convinced him of the need for clear, concise pilot books tailored for the amateur yachtsman. Despite having little experience of navigation, he found himself a publisher and an ex-Dover fishing lugger, Lady Harvey, normally sailed by a crew of three, and set to work.

His hired hand, a mere boy, left soon afterwards and he learned to sail her alone – no mean feat when the main boom was 30ft long!

A number of other craft followed over the years, and five volumes of Sailing Tours, covering Essex and Suffolk, the Nore to the Scilly Isles, Falmouth to the Loire, Land’s End to the Mull of Galloway and the Clyde to the Thames, were published and revised from 1892 until 1909.

I first came across his books after a short mention of him in an Imray pilot book. Intrigued, I bought two of his books online and have been captivated ever since. Witty and wistful, his writing is a joyful ode to cruising.

‘My memory is so crowded with the multiplicity of lovely nooks, fascinating islands and sunny seas that it is a difficult matter to disentangle the mazy strands of the past,’ he wrote. ‘The fact is, I am not a sailor. I just love sailing as a delightful means to a more enjoyable end.’

The origin of cruising

With no electronic navigation aids and only the Admiralty Pilot and charts to navigate with, Cowper’s kind of sailing is hard for today’s yachtsman to visualise. There were few facilities for visiting yachts, and things such as lightships, buoys and lighthouses were sparse.

That, of course, is what he set out to change, and in doing so he laid the foundations for the type of cruising we enjoy today. His obituary from 1930 sums him up well.

‘From his earliest days Mr Cowper took cruising to heart and did more to popularize this particular way of life than any man of his day. It is almost inconceivable to us now the prejudice which existed in the public mind against the man who did not employ hands aboard his yacht. But it was through this veteran single-handed sailor’s adventures and writings that the public began to recognize small yacht cruising as a sane man’s pastime.’

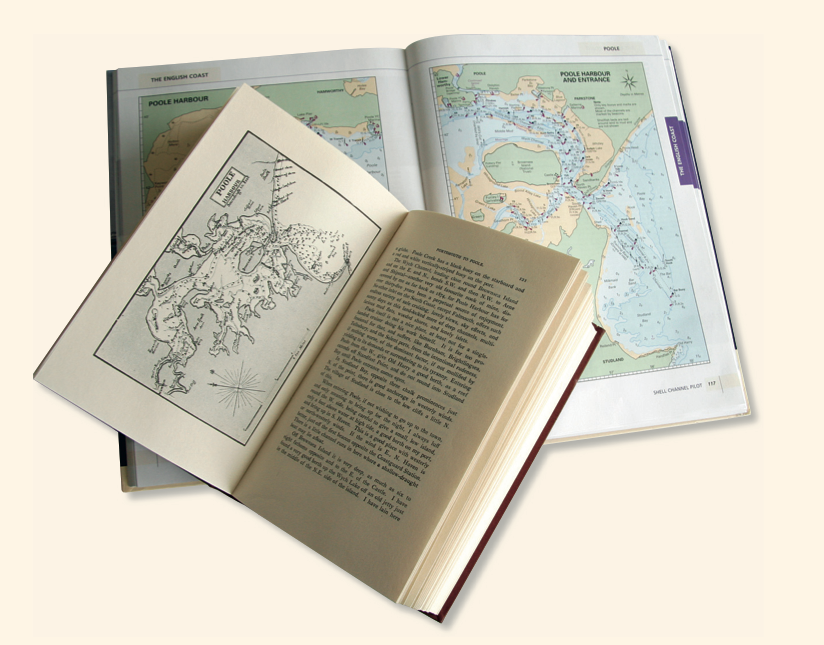

His books are the foundation for today’s detailed, full-colour pilot books upon which we all rely.

Each section of Cowper’s coast is covered with pilotage notes and a ‘gossip’ section, in which he recounts his own voyages and experiences: a fascinating kaleidoscope through which to view the ways in which our coastal ports and towns – as well as how we sail – have changed over the intervening century.

Cowper recalled an almost total lack of yachts when he started cruising in 1878, but by the time the second editions came out in 1909 things had changed:

‘Now every creek from the Alde to Helford River is crowded with small craft; the Crouch is blocked; the Hamble throughout its whole length is chock-a-block. The sport of cruising has become one of the most popular pastimes of the nation.’

Cowper played a large part in this by blazing a trail as an amateur, venturing where very few had gone before him.

My very own sailing tour

In the depths of a January gale, with the wind and rain pounding on the roof, I poured a large drink and spread out charts, dividers, The Shell Channel Pilot and Cowper’s Sailing Tours, with which to plan the next year’s cruise down-Channel. Soon I had discarded the Pilot, neglected the dividers, rolled up the chart and was lost in Cowper’s colourful descriptions and playful narratives of places I could recognise, as well as those that I hoped to visit.

Passage planning could wait until the summer.

The Solent, then and now

Today, nearly 4,000 owners keep their boats on the crowded river Hamble. Cowper did the same. He wrote in 1909:

‘As far back as 1874 I sailed up to Bursledon, then a deserted and charming little duck pond. There is no place within easy reach of London that I can so cordially recommend as this delightful little pool. The other day I was asked by some people going in for small yachting which I should recommend, the East Coast creeks or Southampton Water. I thought of Bursledon. But there really is very little room for more boats.’

More than a century later, it’s still a crowded mecca for all things boaty: but should Cowper, who died in 1930, see it now – with its gargantuan Swanwick Marina – he wouldn’t believe his eyes. But he might still prefer it to Portsmouth.

‘In Portchester Lake, a small mine was sprung 40yds off, and the water actually fell on deck. In the Hamble River there is freedom from this sort of joke.’

Familiar Weymouth

Cowper’s witty and wistful writing accompanies detailed chartlets of every harbour and inlet around the coastline

On any trip down-Channel, Weymouth is still a popular stop. Cowper liked Weymouth.

‘It’s a good place to lie… the harbourmaster shouts directions from the pierhead… but there is very little room inside.’

He thought that it would be much improved should the Great Western Railway’s plans for the harbour, with development of the pier which we can still see today, be undertaken – supposing that yachts are actually allowed to use the harbour.

‘The tendency is to keep harbours for the special use of those making them,’ he complained.

Portland Bill

Portland Bill has become no less dangerous since Cowper’s time. I recall trying to make ground to the west in a light-wind race and hearing the ominous rumble of the breakers as the tide carried us towards them. Cowper was similarly scarred.

‘In passing Portland Bill I have always (except once) kept in as close round the bill as possible. In this way I have always had quiet water – except twice’, he wrote, mysteriously.

He later elaborates:

‘I shall not soon forget my experience of the Portland Race,’ he wrote. ‘Lady Harvey was carried through, helpless as a turtle on its back, pirouetting and sluiced from stem to stern as a warship after coaling. There may have been danger, but I was far too battered and hustled to think about it.’

We lucky modern-day sailors have GPS and computer-modelled tidal charts to show us the set of the tide as it flows around the Bill: Cowper had the Shambles Light Vessel, which lay to the tide where a pair of Cardinal buoys sit now, hooting mournfully at passing craft.

He has an ultra-simple method of tidal prediction which we can still use today. Instead of tide tables giving accurate-to-the-minute times far into the future, he simply provides his readers with the time between high waters – for Portland it’s 6 hours and 35 minutes. So if you know the high tide for any fixed day, you can work out the tide times for any other day. It’s simple, but it works.

Dartmouth

Next port of call for many yachts on passage down-channel is Dartmouth. Many struggle to identify the entrance in the early morning twilight after a night’s passage across Lyme Bay.

Cowper described it as ‘the most baffling, anxious place I know to enter. I’ve [done so] two or three times, but always with much misgiving.’

He nonetheless regards it with affection, even if ‘coal hulks are a veritable nuisance. For beauty, variety of scenery, shelter and a quiet berth, Dartmouth beats any place on the South Coast.’

Start Point

Start Point is the next headland en route to Plymouth. His description sounds forbidding, but shows just how much hard-won knowledge he manages to cram into his descriptions.

‘The rugged appearance of this headland, with its sharp reefs, like cocks’ combs, cropping out along the crest of the bleak hill behind, is very remarkable. It is advisable to give the Start a wide berth. Those acquainted with the place may, however, work to windward and so cheat the offing stream by turning in short tacks along the shore. It is risky for a stranger!’

Plymouth

From Start Point, many will head for Plymouth.

‘Plymouth is another Portsmouth, only much more beautiful,’ wrote Cowper.

Today, the town and its tower blocks appear less than beautiful from the water, but the surroundings and Plymouth Hoe are certainly impressive. Cowper describes the approach as easy, with the imposing landmark of the Mewstone rock sitting to the east of the entrance.

‘I have passed between the land and the Mewstone,’ wrote Cowper, ‘but I do not recommend it – very little is saved and a good deal may be lost’.

His extensive cruising and experimentation shines through in his book – if there’s a narrow rocky channel, you can be sure that he will have sailed through it and can advise his readers from first-hand experience.

Once inside Plymouth’s breakwater, most visiting yachts today will head for one of the marinas near the Cattewater. In Cowper’s day, this was ‘the usual anchorage for merchantmen and yachts.’ He preferred to anchor up the Lynher and Tamar. ‘I avoid Plymouth generally,’ he wrote, ‘it is not my kind of place. Although it is most convenient for shopping, with plenty of life and gaiety.’

Across the Channel

These elaborate signals were to be found displayed at the pierhead of French ports to show the depth of water in the offing and whether the tide is rising or falling

These days, if we want to cross the Channel we load ourselves down with electronic safety devices, liferafts and the like, and equip ourselves for the shipping lanes with radar and AIS. It’s a big step, and newcomers to sailing rightly look upon it as a rite of passage.

In Cowper’s day, amateur cross-Channel trips were few and far between. He wrote:

‘Of accounts of cruises in these waters I found none, except a very sketchy narrative of a trip from Lymington to Brest.’

Cowper armed himself with the material available, but found that others were less than supportive.

‘I always… obtain the best general chart of the locality I can. Armed with these facts, one can disregard the warnings of those who know nothing about the matter. Had I yielded to the nervousness a perusal of that unpoetical but useful book, The Admiralty Channel Pilot, tended to produce, I should never have started on my voyage. In the event, I can safely say I have never made a voyage with so little risk, trouble or hardship as I did my run from Falmouth to Brest.’

Dire warnings

‘I would any time rather cross from England to France,’ Cowper wrote, ‘than I would beat up from Portsmouth to the Thames. But fogs are chiefly to be dreaded. Somehow they just seem to happen when there are steamers about. I cannot say I have the terror of them: they do cause a little anxiety, but they do not occur every day.’

Pilot books have the same effect on us today. The pilot book’s dire warnings of the dangers off Pointe Corbiere in Jersey nearly dissuaded us from visiting in a fresh Force 6 last year. But in the event, all was well, and we scooted round with two reefs slabbed in the main and the washboards tied in.

Customs and free movement

These days, with the EU and the Schengen agreement, we can supposedly roam throughout Europe at will. In Cowper’s day, that of the entente cordiale, no one really paid attention to the small British cruising yacht in France. Or so he thought.

‘It was not until I left French waters that I found that I was an object of suspicion to the authorities, and that two small cruisers had been asked to keep an eye on me. This kind of attention really adds to one’s importance. One might grow egotistical if this sort of thing went on too long.’

We’ve all witnessed boardings by French customs at sea. As ever, Cowper has some good advice that could usefully be heeded today by those boarded by Les Douanes:

‘It does not do to play jokes on French officials. A Frenchman has a great idea of his own dignity. He is anxious others should have the same idea.’

Cowper’s boats

Reading Cowper’s tales of derring-do, presented as matter-of-fact accomplishments, our boating feats today seem somewhat diminished. The elements might still be wet, cold and uncomfortable, but often, down below in the snug, dry cabin, the chart plotter shows us our route and position to within a boatlength, and a modern diesel engine is ready at the push of a button to take us out of trouble.

But Cowper sailed his enormous, unwieldy gaffers single-handed in all conditions and with no modern nav aids – a remarkable feat and fine show of seamanship. His first yawl, Lady Harvey was not ideally suited to single-handed sailing. ‘I remember the old Lady Harvey well,’ wrote Cowper’s contemporary Francis B Cooke in 1919, ‘and she was certainly a lump of a boat for one man to handle for months on end.’

Nonetheless, Cowper covered some serious miles in her before eventually selling her in 1895 to design and build his ideal cruising boat, Undine II, which became his favourite yacht. He rigged her as a ketch and sailed her single-handed from the East Coast and along the French, Belgian and British coasts to the Loire, before selling her in 1899.

More boats followed: The yawl Zayda, the French fishing lugger Idéal, the 14-ton cutter Little Windflower and finally, in 1921, the 41ft cutter Ailsa. In these he explored and meticulously updated Sailing Tours as well as writing a host of sailing yarns and books.

The grand old man of British yachting died in a convalescent home in Winchester in 1930. It’s the least that we, his sailing descendents, can do to get out there and enjoy the waters that he so carefully documented. In 1909, he wrote:

‘When fast and comfortable small cruisers are more easily obtained, men will more readily go farther afloat. The cheapness of the holiday is sufficiently obvious. No other pastime gives so much for so little, and at the same time appeals to the amour propre of a man.’

That we still do so is in no small part thanks to the efforts of one Frank Cowper. Thanks, Frank.

Quotes from Frank Cowper on:

Littlehampton: ‘I sank one boat. It looked very funny by moonlight, cocking up its stern and going down like a duck diving, but it was really not my fault.’

Motorboats: ‘The owners call it sport. One thing was in its favour: it did not last long nor take much seamanship, apparently. However, I should be glad to have a motor in my boat. To possess one is to possess the acme of comfort, provided it does not smell, explode, get in the way, or give out just when you most need it.’

Bacon: ‘If fond of good bacon, I advise them to take a store with them. They will find none of it in France. Eggs in plenty, but no ‘am and eggs for breakfast unless they have a stock of prime Wiltshire with them’.

Englishmen abroad: ‘In France I found that no notice was taken of what they looked upon as the natural eccentricity of an Englishman who, like the fish, was not born to be drowned.’

Getting hold of your own copies:

Frank Cowper’s books are currently out of print, but you can still buy them in secondhand bookshops and online. Originals are pricey and rare – but, as we go to press, there is a full set for £500 in Cambridge. They were reprinted in the 1980s, and these are more common, often selling for around £10-£15 each on sites such as Amazon.co.uk and Abebooks.com.