On the 130th anniversary of Joshua Slocum’s circumnavigation departure, Ian Nicolson discusses the reality of his seamanship feats

Joshua Slocum was 51 when he cast off to sail alone around the world from Boston on 24 April, 1895, with $1.50 in his pocket.

His first encounter with the Spray, a 36ft 9in oyster fishing vessel, was as she lay high and dry in a field by New Bedford Harbour.

She was a gift from a retired whaler, and it was said that the sight of the sloop, whose sailing days, like Slocum’s, seemed done for, stirred him deeply.

He spent 13 months’ labour and $553 rebuilding her. ‘It was the start of one of the world’s great love affairs,’ says Slocum’s biographer.

A 1995 Robbert Das pen/watercolour drawing of the Spray, courtesy of The Maritime Art & Design Foundation, Holland. Original Robbert Das pen/watercolour drawings are for sale at www.maritime-art-design.nl/

He rebuilt her more or less single-handed. The job included the difficult work of dismantling and renewing the ‘backbone’, replanking, reframing, fitting new floors and beams, putting on a new deck, new cabin coamings and a simple accommodation.

During the rebuild, he drove in 1,000 bolts and probably made many of these himself. To me, this was his greatest feat, exceeding his stunning seamanship.

Comparable rebuilding projects have taken three shipwrights over a year. Admittedly, they would not work six days a week and very long hours each day as Joshua Slocum did, but he had no electric tools, and he was far from young at the time.

Spray’s self-steering ability

There are supposed to be two mysteries about Spray, namely, why was she so good at self-steering, and why was she so fast?

However, there is no real surprise that she had these characteristics. Fishermen need to work on their boats while under way, and they are often short-handed.

A hull and rig which combine to give self-steering not only frees the crew from the tedium of long hours at the helm; it also ensures that the rudder is not acting as an intermittent brake, slowing the boat.

Poster advertising the novel Sailing Alone Around the World by Captain Joshua Slocum, 1903, from the New York Public Library. Credit: Gado Images/Alamy

When a sailing yacht heels, her underwater shape becomes asymmetrical.

We know a lot about asymmetrical shapes moving through any fluid, whether the medium is air or water.

As the fluid flows over the shape, there is less pressure on the fuller, more bulbous side than on the flatter side. This is why aeroplane wings are well-rounded on top and flat underneath. It’s why propellers are rounded on one side of the blade and flat on the other – to get a sideways force, and hence ‘lift’.

These things need asymmetrical shapes if they are to work.

With a sailing yacht hull, this lack of symmetry is, in one respect, a considerable nuisance.

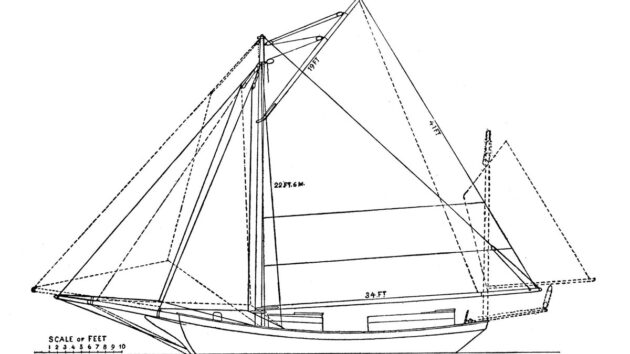

The lines of the 36ft 9in Spray. Credit: Granger – Historical Picture Archive/Alamy

It means there is a side force on the hull and, almost always, that force is forward of amidships and usually from the lee side up to windward.

This is why sailing yachts want to round up into the wind.

To keep them straight, we hang on to the tiller, pulling it to windward to counteract the turning tendency, which we call weather helm.

What made Spray’s hull shape special was that as it heeled, the underwater shape did not change much:

- She was so beamy and so stiff that she did not heel much.

- Her shape was such that when heeled, the lee side was, by clever design, not greatly different to the windward side, so the water pressures were about even on both sides, and hence, there was not much turning moment.

Lashing the helm

Spray did have a slight tendency to turn into the wind. This was counteracted by Joshua Slocum, who lashed the helm a little to weather.

The old boy knew just how much helm to apply with different wind strengths, so as to ensure continuous ‘tracking’ in a straight line.

There is more to it than just counteracting the slight imbalance of the hull with a little permanent rudder angle.

Joshua Slocum used all those tricks which were fashionable before the coming of self-steering devices.

Joshua Slocum rows the Spray out of Melbourne harbour, in the course of his solo circumnavigation,1896. Credit: Chronicle/Alamy

The headsail sheet is slightly hauled to weather (cruising folk have been doing this long before the racing world invented the Barber hauler), and the mainsheet is slackened a trifle.

This forces the bow off the wind, till the pressure on the mainsail starts to increase, and forces the bow up wind again.

Other tricks include leading the headsail sheet further forward, reefing the main, so as to shift the centre of effort forward, tricing up the tack of the main, and dropping the top of the gaff.

All these tricks are used to reduce the tendency of the boat to swing up into the wind.

Every fisherman wants his boat to be fast so that he can fish further away from base, and still get back in good time.

He also wants to be able to beat the rest of the fleet home to get the best prices and the best berth alongside harbour.

Spray’s speed

It’s no surprise Spray was something of a flyer off the wind. To windward, she was slow because she had a low rig and a shallow draught.

To make things worse, Joshua Slocum took her centreboard out when he rebuilt her.

It’s a basic principle of yacht design that if you want to make rapid progress to windward you must ‘Go high in the air, deep in the sea’.

Joshua Slocum rebuilt Spray and sailed her single-handed round the world, 1895-1896, Credit: Chronicle/Alamy

This means having a lofty rig and a substantial draught.

Spray’s lines show why she was fast. The run, that is the slope of the buttock lines towards the stern, is shallow, being about 10° to the horizontal.

Other things being equal, the smaller this angle, the faster a boat will go.

We once got an extra third of a knot from a 45-footer when tank-testing by making a quite small reduction in the slope of the buttock lines.

When the vessel was built, the improvement thus predicted was proved right. The lines also explain why she would hold her course at sea with no-one at the helm.

She was what is called ‘balanced’, something like a double-ended canoe with similar bow and stern lines.

A drawing from 1896 showing Joshua Slocum and Spray leaving Sydney, Australia, 6 December 1896, in the new suit of sails given by Commodore Foy of Australia. Credit: Granger – Historical Picture Archive/Alamy

When she heeled, she had little or no tendency to luff up.

These days, almost all yachts try to luff all the time, and this is counteracted by pulling the tiller to windward.

Many yachts need a firm hand on the tiller (or the wheel), especially when they heel a lot, if they are to be kept going straight.

Due to her wide beam, Spray would not heel a lot under normal conditions, and this helped her sail a straight course.

She was as stiff as a church, as shown by her lines and proved by the occasions when Joshua Slocum could not reef quickly.

There is one fascinating aspect of her lines, which are published in several books.

All these plans are based on the set taken off by G D Mower when Spray was hauled up at Bridgeport.

It is quite common for someone who is not used to taking off the shape from small craft to misjudge the exact waterline because there is normally some weed growth around the flotation line.

This regularly leads to the load waterline being misjudged and taken as too high.

It is not unusual to get the level too high by 3in-4in and sometimes more. So all those numerous calculations which have been done on her lines over the past 100 years are somewhat adrift, as she did not have a freeboard of about 1ft 9in as has been so widely discussed, but at least 2ft 1¾in, and maybe more.

In other words, she was not quite such a heavy tub as has frequently been suggested.

And this helps to explain why she was no sluggard downwind, because if anything is certain afloat, it is that lightness means speed.

By today’s standards, she was a heavy displacement yacht, but she did not have to carry around the weight of an engine with its shaft, sterntube, batteries, exhaust piping, plumbing, and so on.

She had little furniture or domestic equipment, and lacked many of the things which go to make up the total weight of a modern yacht.

Shifting ballast

All the ballast Spray carried was inside, stowed below the sole. Joshua Slocum specifically said his yacht had ‘…no iron or lead or other weight on the keel’.

She was a beamy vessel, so if a few pigs of ballast were moved from the lee side to well out to windward, the lever or distance moved would be considerable.

This would make the vessel stand up to a breeze more effectively, and the hull shape being driven through the water would cause less resistance.

Shifting ballast helps most when going to windward, but it is well established that Spray was not good at beating, and Joshua Slocum sensibly followed courses which minimised this point of sailing.

Getting ballast weight to windward also helps on a reach, and there were plenty of occasions when the yacht was on this point of sailing.

With a wide yacht, a small amount of weight shifted is much more effective than adding weight to the keel or deepening the ballast keel.

On a few modern craft, there are water ballast tanks amidships well outboard, port and starboard.

Joshua Slocum is acknowledged as the first solo circumnavigator, although he sailed through the Magellan Straits rather than round Cape Horn. Credit: Granger-Historic Picture Archive/Alamy

When the windward one is filled with water, it has a significant and valuable effect on the stability of the vessel.

Joshua Slocum writes that ‘the ballast, concrete cement was stanchioned down securely’. Sure, most of it.

But in his day, plenty of pieces of semi-portable trimming ballast were common. It was normally composed, at least in part, of standard 55lb iron pigs.

This is a handy weight, easy enough for one person to shift quite quickly.

Some of the trimming weights would almost certainly be stones off the shore, because this is the cheapest form of ballast, and was widely used along the American East Coast.

It may be argued that Joshua Slocum does not mention shifting ballast in his book. But why should he? It was common practice.

He lived in a time when getting a bit of extra speed under sail using every trick in the book was critical all over the world, in every sort of craft.

Speed meant money for merchant vessels then as now.

Rather more importantly, being able to coax a smidgen more speed meant slipping away from a hostile ship.

Shifting ballast to windward was, at times, a lifesaving technique used to escape from pirates.

So, did Joshua Slocum shift ballast to windward? I think he did, at least occasionally.

I suspect on his last voyage he may have got caught ‘aback’, with the ballast on the wrong side when the wind made a major shift, perhaps when he was asleep.

By then, he was getting on in years. With her relatively low freeboard, having the ballast on the wrong side could have been fatal for Spray.

Joshua Slocum’s disappearance at sea has always been a matter of speculation, and this could be the cause.

One of the problems which comes up when reading Joshua Slocum’s book Sailing Alone Around the World is his standard of accuracy.

He wrote in the manner of his time, when scientific precision was not as dominant as it now is.

Take the matter of the dinghy. Never a man to waste time, or avoid a challenge, Joshua Slocum got hold of an old dory when he needed a dinghy.

He says he cut it in half, as it was too big to stow on board.

At face value

I’ll bet he didn’t.

I’m virtually certain he cut a third off, or maybe two-fifths. If he’d cut it in half, he would have ended with a horrid little boat which would have trimmed badly down by the bow, been a shocker to row or tow, and looked ugly.

But we know what he means when he says he ‘cut it in half.’

And how like him to make a simple adaptation so that what was not much use to him at 9 o’clock in the morning by tea-time was a practical yacht tender.

It may be argued that I’m a bit cavalier in treating Joshua Slocum’s book as a fascinating but not totally precise document.

I’m sure Joshua Slocum was not deliberately careless or inaccurate when writing, he was just following current trends.

Captain Joshua Slocum. Credit: Chronicle/Alamy

A typical example of this is seen in the way voyage times and distances were measured before 1900.

It was common enough to describe a voyage as taking 22 days and leave it at that.

What was not added was the precise departure time, which could be the last moment when the final set of back bearings was taken on the headlands disappearing below the horizon astern.

The voyage time, when spoken about later, might not include the day of departure when hours were spent warping out of the berth and drifting on the tide well within sight of the harbour.

The next day… or two… might be omitted from the voyage time because they were spent creeping along the shore in light airs, still almost within sight of the port of departure, and well within signalling distance of a headland.

Just as the ‘first day of the voyage’ might be described as the time when land was dropped astern, the same applied at the end of the voyage.

We tend to think of a voyage as terminating when we secure alongside in a marina, or at least cross the bar into an estuary.

But 130 years ago, a voyage was sometimes considered complete (as far as the records go) when landfall was made.

Even if the moment of landfall was not taken as the end of the voyage, the day and time when the tug got a line across to the freighter often was.

All this is confirmed in the book Capt. Joshua Slocum, written by his son Victor.

Plaque on Brier Island, Nova Scotia, commemorating Joshua Slocum, who grew up there. Credit: Gary Corbett/Alamy

In it, he mentions that the ship Northern Light, which Joshua Slocum commanded in 1882, was towed 150 miles down Long Island Sound, before the tow line was dropped and the voyage was considered as properly begun.

So Joshua Slocum’s ‘voyage times’ may be less precise than ours, though entirely in line with general practice at the time.

This means that some of his fast passages were perhaps not quite as swift as they seem.

His standard of seamanship when single-handed, however, was far ahead of what most of us can achieve on a good day, with favourable weather, an easily handled rig, a fat diesel engine and a full crew.

Joshua Slocum Fact File

- Joshua Slocum returned from his circumnavigation to drop anchor at Newport, Rhode Island in June 1898, 46.000 miles, three years, two months and two days later.

- According to a reporter at the scene of his departure, Joshua Slocum was 5ft 9½in tall, and was as spry as a kitten and nimble as a monkey.

- Eleven years after his solo circumnavigation, Joshua Slocum set out alone again, bound for South America. He and Spray were never seen again.

- Joshua Slocum, born on 20 February, 1844, was declared legally dead as of 14 November 1909, the date on which he last set sail.

Around the World

Joshua Slocum is acknowledged as the first solo circumnavigator.

The International Association of Cape Horners says the first recorded circumnavigation was begun by Ferdinand Magellan in 1519, who led a five-ship fleet from Seville, Spain, with the aim of finding a route westwards from Europe to the East Indies via the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, before returning across the Indian Ocean.

Like Magellan, Slocum also went westabout, setting out from Boston on 18 April 1895 and returning on 27 June 1898.

It was an amazing voyage, but since he chose to cut through the Magellan Straits rather than round Cape Horn, his achievement is excluded from modern records.

Sailing solo: how to go from crewed to single-handed

Round the world sailor Ian Herbert-Jones shares valuable advice on how to transition from crewed to single-handed sailing

Tony Curphey the man who sailed four times around the world

“In the six years I’ve owned Nicola Deux I’ve sailed 77,650 miles in her. I just love Nicholson 32s. My…

Jessica Watson – the real sailor behind the True Spirit film

Whilst the new Netflix True Spirit movie was being filmed, celebrating Jessica Watson's real-life teenage solo, non-stop global circumnavigation, the…

“How I sailed around the world in my 32ft yacht”

The fifth finisher in the 2022 Golden Globe Race, Jeremy Bagshaw shares how he prepared his OE32 for a circumnavigation

Want to read more articles?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial, in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter