How to calibrate your boat's speed, depth and wind instruments - to ensure they're reading accurately

There are two main methods for calibrating your boat’s speed instrument: The measured mile or the SOG check.

The simplest way these days is to use the GPS speed over ground (SOG) figure to check against.

However, it will only be accurate if you can use some water unaffected by tide: in a locked marina basin, or at slack water.

If escaping the tide is not an option, doing two runs – one uptide and one downtide – will give you a vague average, but slack water is best.

Calibrate your speed using a measured mile

The traditional way to calibrate a log is to use a measured mile. This can be between two waypoints: alternatively, in many harbours there are still measured mile transits marked out on the shoreline.

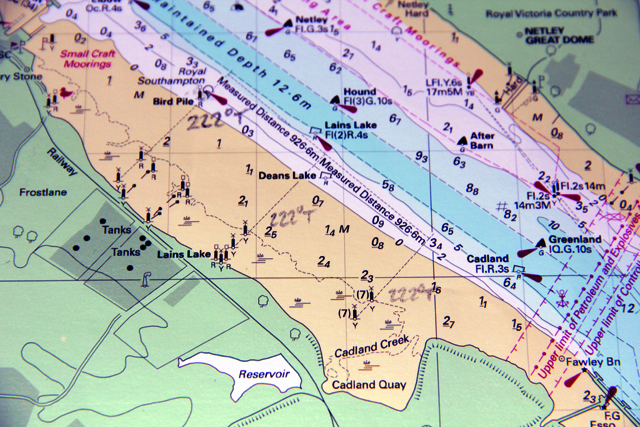

One of these is on the west bank of Southampton Water, with a measured mile marked at each end with a transit.

We set the engine revs at a comfortable speed and engaged the autopilot. When we passed the first transit we started the stopwatch, halting it at the end marker, before turning 180° and doing the same run, this time downtide, noting the ‘distance run’ figure each time. At the end of the two runs, we could work out the sums to check the accuracy.

These daymarks at Lains Lake in Southampton Water mark the halfway point of a measured mile that is marked on the chart….

Run 1: Time 17:48

Distance run: 1.34NM

Run 2: Time 10:10

Distance run: 0.86NM

As you can see, there was some tide running! It would be preferable to do this in slack water.

The average of the two distances run, as shown on the boat’s log, was 1.1NM.

Converting each of those times to decimal hours and dividing the distance by the time gave us an average speed for both legs of 4.51 knots for the outbound leg and 5.07 knots for the return leg – or an average of 4.79 knots.

A further check was made by looking at the average speed seen on the speedometer – it averaged 4.5 knots on the way out and 5.1 knots on the way back, an overall average of 4.8 knots.

Our distance run over the ground showed that the speedometer was very slightly over-reading. By entering the log’s calibration mode we could adjust the calibration factor, which had been set at 16%, until it matched up.

Some systems, such as Raymarine’s i60 series, have an automatic calibration programme, where you can press a button to start and finish your measured mile. It prompts you to carry out four runs, and automatically does the maths to calibrate the log.

How to calibrate a depth sounder

Most people like to know the depth below the keel, which means adjusting the offset between the transducer and keel to the correct figure. The easiest way to do this is afloat is to use an improvised leadline to measure the depth of water on your mooring and adjust the offset to match.

However, for a truly accurate reading do the job out of the water, using a tape measure.

…but you can do it afloat by measuring the true depth of water and subtracting your known draught to gain the depth below the keel. Adjust the offset so that the sounder shows the same figure

How to calibrate a wind indicator

The problem with wind speed is trying to find a reliable source against which to calibrate the speed.

You can sail close to a wind station (the Solent’s BrambleMet beacon is one example): these only update every few minutes, but will give you a ballpark figure.

Better still is to compare your reading with a number of boats alongside. If your readings are consistently too low, it’s worth checking the bearings of the anemometer cups.

How to adjust your instrument’s wind angle

The wind angle is easier to adjust than the windspeed. Some instrument systems will ‘learn’ the wind angle if, in calibration mode, you sail close-hauled first on one tack and then another.

Even if your instruments aren’t that clever, you can check the angle yourself by ensuring your jib cars are in the same place on both sides and noting the apparent wind angle reading on both tacks.

If it’s out, you can adjust it plus or minus a few degrees to compensate.

Another way to assess the wind angle is to motor fast head-to-wind, cross-referencing it with your masthead wind indicator – or send someone up the rig to hold the arrow exactly head-to-wind while you adjust the calibration.

Cross-pollination

You’ll find that if one instrument on a network is mis-calibrated, you may get some odd readings on your other instruments. The most common place for an error is in the true wind speed. The instruments work this out using the boat’s speed through the water and the apparent wind angle, so if your boat speed is reading incorrectly, you are likely to also have problems with the wind speed.

If you liked this, you might also be interested in reading these:

How to swing a compass

Before GPS sets became so ubiquitous, swinging a compass was a yearly ritual for most boat owners, and the compass…

How to work out tidal height calculation

PBO contributor Sticky Stapylton explains how to work out tidal heights for standard and secondary ports

Video: How to scull over the stern

Learn a useful traditional skill that could get you out of trouble

The hard sell…

Did you know that Practical Boat Owner magazine (out every 4 weeks) is the UK’s biggest selling boating magazine and has been ever since it was launched in 1967. We cover sail and power, paddle and scull, kite and foil… you name it we float it.

Subscribe, or make a gift for someone else, and you’ll always save at least 30% compared to newsstand prices.

See the latest PBO subscription deals on magazinesdirect.com