Tired of battling tides, John Willis fits a new common rail diesel engine in his pilothouse yacht

Late evening turned to night as Pippin fought adverse tides off Corbière, hard on the wind, her old Yanmar straining against the elements like a featherweight pushing Mike Tyson. To be fair to the engine, Pippin – svelte though she is – weighs a comforting 8 tons loaded, so it was an age before I could bear away and let the sails take the strain.

Of course, Pippin is a sailing boat, but sometimes I get it plain wrong and the Channel Islands’ formidable tides turn on me, or I simply want to get home for the Southampton game. I’m no sailing purist and an extra knot from Jersey to Guernsey saves the best part of an hour; make that 100 miles and it’s over 3 hours.

As I again sat admiring a near-static seascape, I decided it wasn’t unreasonable to want my boat to both sail and motor to her potential; maybe it’s to do with age, but I dreamed of a Pippin capable of bettering 6 knots at 70% of maximum revs and cracking hull speed in a rush for the first time in her 24 years, a dream I could finally afford due to a timely house sale.

Article continues below…

How the diesel engine works – take a look at Maximus’s Volvo saildrive

Checking the diesel engine after a long lay-up is an essential task before launching any boat, says marine surveyor Ben…

Engine health check: 6 steps to make sure your diesel is in fine fettle

An idea struck me when I ordered an oil analysis for Merlot, my lockdown project boat. Routine health checks are…

But nightmares followed. Which engine make? ‘Common rail’ or ‘conventional’? On the internet there are zillions of arguments in favour of most engines – except common rail diesel engines for small yachts.

Agonising research

I poured my agony into comparative spreadsheets and that led to a swift decision, for I hate faffing; a decision that brought another wave of doubt for I had chosen an £8,000 Yanmar 3JH 40CR. Yes, it’s a common rail diesel engine (the world’s smallest) but the internet was rife with dire warnings.

However, like the first hint of a sea breeze, I sense the opinion tide turning to embrace this not-so-new technology, an embrace I made happily as I can no more mend a mechanical thingamy as fix a fault on an electronic control unit – but I can do the basic maintenance required by any diesel.

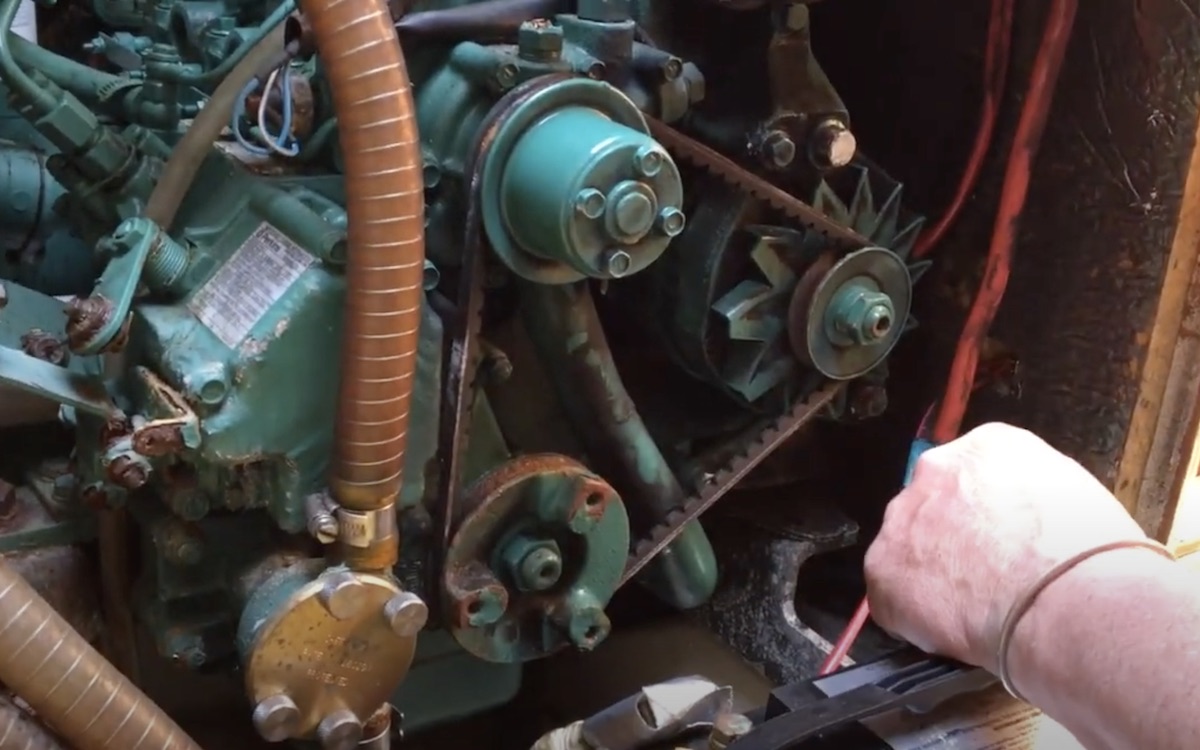

The original engine struggled to keep Pippin moving against adverse tides

Then there is the environmental issue. Though well maintained, my old Yanmar doggedly wept its life fluids, straining all 950cc to provide forward motion, its sweaty labours evident from the smoky grey transom and a thick beard of pollution along the water line, which I dutifully scrubbed from time to time. By comparison, this common rail diesel engine is cleaner running, slightly more economical and produces comfortably more torque than a well-known ‘conventional’ competitor.

I worked out how much the project would cost then doubled it by handing it over to an expert. The total engine installation would later add up to £12,000; an old boat like Pippin has tight spaces requiring a bespoke installation, not to mention the inevitable discovery of things to be fixed.

Removing the old engine

Getting the old 130kg engine out was easy enough and it was a shock to see just how tiddly it was, as it sat forlornly in the workshop, weeping gently. By comparison the new 1,642cc, 192kg beast looked a whopper, so I rushed off to measure the companionway again only to decide it was impossible! But the engineer calmly disagreed and who am I to argue, so I slunk off to don coveralls and scrub out the engine bay.

Old engine out and time for a tidy up.

The new engine had to be mounted further forward so a longer propeller shaft was required, which couldn’t be fitted with the engine in situ due to the rudder’s location.

A larger propeller was impossible, but the Darglow engineers considered the problem and sent a new hub cartridge to alter the pitch of the blades for the 16in feathering prop – it was spot on.

Significant ‘surgery’ was required to create extra space; no surprise but scary nonetheless. After some consideration, the engineer deduced a way to open up the engine bay.

A longer prop shaft was required

He lowered a non-structural longitudinal under-floor bulkhead alongside the engine, and made a cut out in the transverse underfloor bulkhead just in front of it.

Some 9mm thick stainless steel flat bars were then machined to fit over the top of the bearers to take the new engine mountings.

Bigger in, bigger out

The larger engine required more cooling water, necessitating a larger opening in the keel and a new seacock – an excellent opportunity to remove the old raw water strainer from deep in the bilge, and to place the replacement Vetus unit beside the engine.

New Vetus water lock

Bigger in bigger out, so a larger diameter exhaust hose was installed as the money meter ticked inexorably on. Somehow a Vetus water lock was squeezed under the cockpit and a bigger exhaust hose was run up high into the stern and down to a new larger hull fitting.

An anti-syphon unit was fitted inside the pilothouse locker, with a drain out into the cockpit.

One thing a common rail diesel engine must have is fastidiously clean fuel. Having previously encountered diesel bug, I had a Racor fuel polishing system fitted which can polish an entire tankful three times an hour, with or without the engine running.

Racor fuel polisher

A little electric fuel pump was reused for recharging the Racor engine pre-filter (not really necessary) after changing its filter, and we added a water alarm.

Unexpected problems

Some unexpected problems arose. For example, to accommodate the fuel polisher’s fuel line, a new stainless steel fuel tank top plate with additional fittings was made up, and in the process the original fuel filler pipe (which was made of the wrong material) snapped, as did the breather pipe.

Naturally joinery had to be dismantled to replace these pipes and so the bill was getting higher and higher. With everything opened up, it was possible to remove some old redundant wiring and tidy the area beneath the pilothouse floor.

New propeller pitch cassette

I also had the unused internal throttle and cables removed, leaving just the hydraulic internal steering. A Yanmar C-35 engine control panel was fitted plus a new fuel gauge. I had tired of the old gauge’s habit of indicating ‘Full’ before plummeting in one fell swoop to ‘Empty’ so a vertically lifting float sender unit was fitted to replace the old swing arm unit.

With the end in sight, we switched our minds to making up a new engine cover, and came up with a simple design of marine ply slide-out panels, fitted between the skipper’s port-side seat and the galley to starboard.

Insulated with soundproof material and finished in veneer and Treadmaster, it replaces the heavy old engine box, plus it makes an excellent seat for galley work.

Engine box doubles as a handy seat for galley work

Common rail diesel engine costs mount up

Dizzy from the spiralling costs, madness overcame me; in for a penny in for a pound, so I sanctioned other projects such as installing Raymarine sonar, reglazing the main hatches and replacing the old cooker with a simple hob and grill, which opened up a large area beneath.

You can never have too much storage and the first mate suggested it was perfect for a storage box to contain my little voyaging luxuries like Marmite, Gentleman’s Relish, Ketchup and cans of smelly fishy stuff.

Even the finest engineers and carpenters aren’t generally known for their housekeeping, and this, coupled with my hoarding habits, meant the cabin was now piled high with a towering bonfire pile of dismembered furniture and newly redundant bits.

Pippin’s helm position

It wasn’t all bad as several long forgotten items revealed themselves in various strange places.

Lockdown occurred on the planned launch date so it wasn’t until several weeks later, on a cold day in March, that Pippin slid gracefully into the water and the engine fired first time.

Out at sea in calm conditions, she surged quietly towards St Martin’s Point with hull speed on the clock and a Cheshire cat’s grin on the skipper’s face.

Relaunch time for Pippin with a new common rail diesel fitted

Pippin’s hull speed is just over 7 knots, and she now settles comfortably at around 6.75 knots with 70% throttle in fair conditions, 1.5 knots faster than before, which should save more than 2.5 hours on a cross-Channel trip to Weymouth – though I’d rather sail it.

The whole project cost £20,000 but with luck I’ll never again have to sit looking at Corbière for two hours… much as I like the place.

About the author

John Willis, 66¼, is an ex-soldier, businessman and school bursar. He’s clocked up more than 20,000 miles, mainly solo, in small boats roaming north to Shetland and south as far as the Azores. He is the current custodian of Pippin, a Frances 34 Pilothouse, and his mantra is that there is never a best time to go and do – so just go and do.

Why not subscribe today?

This feature appeared in the November 2021 edition of Practical Boat Owner. For more articles like this, including DIY, money-saving advice, great boat projects, expert tips and ways to improve your boat’s performance, take out a magazine subscription to Britain’s best-selling boating magazine.

Subscribe, or make a gift for someone else, and you’ll always save at least 30% compared to newsstand prices.

See the latest PBO subscription deals on magazinesdirect.com