Cruising doyen Jimmy Cornell shares 50 years of lateral thinking from his first hull fit out to what he stows as gear essentials...

The challenge of finding solutions to practical problems is something I have enjoyed as far back as I can remember. This was certainly the case when I began fitting out the first Aventura, and as an absolute greenhorn in anything nautical I was forced to come up with answers to complex questions in virtually everything I touched.

As the boat had a centre cockpit and aft cabin, the wheel was too far from the rudder stock so I was advised that the easiest and cheapest solution was to have hydraulic steering. However, that meant that I could not use the self-steering gear whose control lines had to lead to a drum on the wheel or to a tiller.

The solution I came up with was to extend the rudder stock by way of a 2m-long 40mm steel bar to the level of the aft deck and fit a tiller to it. The lines of the Aries gear were easily led to it and thus we could steer both with the wheel and the tiller. Quod erat demonstrandum (QED): ‘Which was to be demonstrated.’

Many of the solutions that followed were rather unorthodox, but they worked and several were repeated on my following boats, such as a day tank for the engine. On a number of occasions, the easiest solution was to do without certain non-essential items, such as a diesel genset or freezer.

The former was the easiest decision because we simply couldn’t afford one. Auxiliary diesel generators for cruising boats were still a novelty in those days and only the largest boats in my survey conducted in the South Pacific had one on board.

Article continues below…

Jimmy Cornell asks how much safer has sailing actually become in 40 years?

Without doubt, safety has been the biggest improvement to long-distance cruising over the last 50 years. This is my own…

What makes the best liveaboard boat? Jimmy Cornell explains what he’s learned

Every voyage starts with a dream and for me it goes back a long while to when I was a…

As our electrical consumption was very modest, and we often used paraffin lamps, we managed to charge our one and only battery by the main engine. On Aventura II there was no need for a genset because one of the twin engines fulfilled that role efficiently.

Aventura III had an additional large-capacity alternator and also a wind and towing generator. By the time Aventura IV materialised, we relied almost entirely on renewable sources of energy by having wind, solar and hydro generators.

As to Aventura Zero, her very name reflects my aim to do away completely with fossil fuels for both generation and propulsion. Not having a freezer was also an easy decision because we never had one at home as we always preferred to eat fresh things.

On the subsequent Aventuras, we did have a refrigerator and learned to preserve food for longer passages by vacuum-packing meat, as well as fish caught on the way, and store them in the fridge.

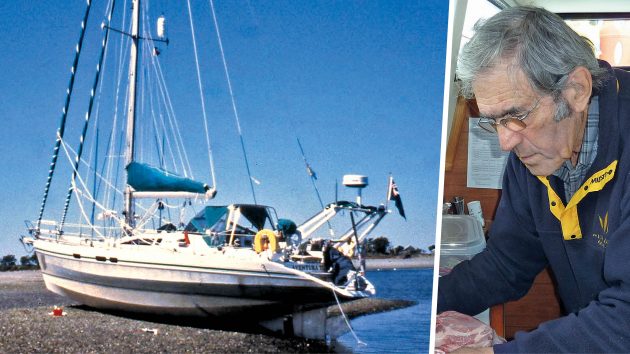

Gwenda steering from the original Aventura’s aft deck

Diving gear

As part of the preparations for our first voyage I completed a British Sub-Aqua Club (BSAC) diving course. I realised that diving gear would be an essential item to have on board, and had a complete set on each of my boats, even a compressor on Aventura II.

A drysuit on Aventura III and IV proved its usefulness when I had to dive in Arctic waters. We also had survival suits that were used once when Ivan and I crash-landed through the breakers on the beach below old Cape Horn lighthouse.

The diving gear and tanks were kept mainly for emergencies, as I was quite a proficient free diver. I spent hours spearfishing to feed the family on our first voyage, but abandoned it when protection of the environment became a major concern.

I continued fishing on passage and we always caught enough to ensure a supply of fresh food for the crew.

Easily accessible liferaft mounted on Aventura II’s stern

Invaluable kit

Perhaps the most important item on board is the liferaft. Because it’s very rarely used, it is often stored in a location from where it is not easy to retrieve quickly and launch in an emergency.

A golden rule is that the weakest member of the crew should be able to handle and launch the liferaft. On all my boats from Aventura II onwards, the liferaft was always located at the stern from where it could be easily launched. All my boats, up to Aventura IV, had a 40lt tank mounted about one metre higher than the engine so that the fuel was gravity-fed to it.

The tank was topped up every four or five hours by manually activating a fuel transfer pump. I deliberately avoided having an automatic filling system and placed the switch for the pump where the person filling the tank could see the glass water separator and make sure that the fuel was clean.

Apart from that pre-filter, there were two more filters before the fuel reached the engine. A further advantage of a day tank was that we always knew we had 40lt of fuel even if the main tank was empty.

Crew up the mast, saving a collapsed spreader en route to the Falklands

Mast steps

Another useful item that can make life easier is mast steps. They were a great bonus when scouting ahead, either when looking for a lead through the ice in the Arctic, or avoiding coral heads in a tropical lagoon.

This task became much easier when we acquired the first forward-looking sonar (FLS), but we continued to play safe with my wife, Gwenda, keeping an eye on the depth and obstructions ahead on the cockpit mounted FLS, while I’d still do my eyeball navigation from the spreaders.

Aventura III’s mast steps probably saved our mast when one of the spreaders collapsed on the way to the Falklands. My crew was able to quickly climb the mast, retrieve the spreader, and then secure the rig with a spare spinnaker halyard.

Dousing the Parasailor

The steps were also very useful to check the rigging or the instruments at the top of the mast. But mostly, they were used to climb the mast to take photos.

Aventura IV’s Parasailor spinnaker (pictured right) was my favourite downwind sail, but it took me a long time to reach that high-tech level.

My search for a functional downwind setup started with a twin-jib arrangement on the first Aventura. The system worked well and was easy to set up as I’d prepared for this by having two separate forestays.

The only problem was the awful rolling, which I tried to dampen by having a storm trysail sheeted hard amidships on the mainsail track. It sort of worked, but I soon realised that the solution might lie elsewhere.

A beautiful mizzen staysail, produced by Gwenda on her sewing machine, was perfect for broad reaching, usually in combination with the mainsail and poled-out genoa.

Aventura II’s first spinnaker turned me into an addict with asymmetric, triradial and, finally, the Parasailor, each playing an essential role in the fast passages achieved on our three following boats.

Shallow draught

In all my world cruising surveys dealing with the subject of ideal draught there was a consensus that whereas a fixed keel may be best for ocean passages, having a shallow draught when cruising is not only ideal for exploring places that other boats cannot reach, but also safe because it allows you to find shelter in a protected spot in the event of an emergency.

Aventura II’s lifting keel fulfilled both objectives, but it was only when Aventura III’s centreboard appeared on the scene that I finally found this to be the perfect solution, as it not only made it possible to reduce draught quickly, but also improved our sailing performance.

I have often been asked how safe it is to sail on a boat without a keel. Having sailed twice across the Drake Passage to Antarctica and back, first on Skip Novak’s Pelagic, and then on Aventura III, both centreboard boats, and having experienced on one occasion winds between 50 and 60 knots, I could vouch for either boat’s stability under such conditions.

Aventura III’s integral centre board meant sheltering from a storm in a shallow bay was possible

They coped impressively well with the high Southern Ocean swell and put any possible doubts to rest. Both Aventura III and IV had an integral centreboard, which meant that when the board was raised, it fully retracted into the hull.

The ballast to displacement ratio of both was 32, which is similar to most other cruising boats. As most integral centreboard boats have a flat bottom, with the board fully up, they can dry out on a beach, which is yet another advantage.

In the words of Pete Goss, whose Pearl of Penzance was an Exploration 45 similar to Aventura IV: “a centreboard’s real advantage is not the ability to reduce the draught but the peace-of-mind attribute.

Aventura II with spinnaker

We were able to surf down Atlantic swells with the confidence of fixed ballast. Being able to lift the centreboard under such conditions meant that she didn’t trip up off the wind and became directionally stable to the point of being docile.

This in turn gave a more comfortable ride, de-stressed all areas of the boat including the autopilot and power consumption.” Shallow draught is a major attraction of centreboard yachts, but there are also considerable performance advantages.

The main role of the board is to provide lift when sailing close-hauled, and to reduce leeway when reaching. With the board fully down Aventura III drew 2.4m and, when sailed properly, it could point as high, or almost as high, as most keeled cruising boats.

Aventura IV from above

With a draught of 2.8m with the board down, Aventura IV performed even better than her predecessor. Aventura Zero had a draught of 0.9m with the two daggerboards raised, and 2.15m with them lowered.

There is a certain technique in sailing a centreboarder efficiently, not just on the wind but off the wind as well. This is when the centreboard becomes a true asset thanks the ability to lift the board gradually as the apparent wind goes past 135°, and to continue lifting it up to the point where the board is fully retracted.

This is a great advantage as the risk of broaching is virtually eliminated. As pointed out by Pete Goss, the absence of a keel to act as a pivot in a potential broaching situation means that the boat does not tend to round up.

This feature has allowed me to keep the spinnaker up longer than would normally have been safe.

Fixed pole – Jimmy’s favourite broad-reaching or running technique

Fixed pole

My favourite broad-reaching or running technique is to set up the pole independently of the sail I intend to use, so that the pole is held firmly in position by the topping lift, forward and aft guys, with all three lines being led back to the cockpit.

Regardless of whether I decide to pole out a foresail or spinnaker, the sheet is led through the jaws of the pole, which is then hoisted in the desired place. Once the pole is in place and is held firmly by the three lines, the sail can be unfurled, or the spinnaker hoisted and its douser pulled up.

With the pole being independent of the sail, the latter can be furled partially or fully without touching the pole. This is a great advantage when sail has to be reduced or furled quickly, if threatened by a squall.

Aventura IV’s windward-sailing capability was put to a good test in the Arctic when we had to beat our way through a narrow strait in 25-knot winds to reach the open sea

Once the squall had passed, with the pole still in place, the sail can be easily unfurled. When sailing under spinnaker and threatened by a squall, I preferred to douse it and lower it onto the foredeck.

Once the danger had passed, the spinnaker, while still in its sock, can be hoisted again, and undoused. My routine became so well-tuned that I could hoist and douse the spinnaker on my own.

The last time I did this it was on a test sail with Aventura Zero off La Grande Motte, the site of the Outremer boatyard. I wanted to show my much younger crew how more brain and less brawn could tame a monster the size of a tennis court.

Parasailor and B&G screen: sailing at 3 knots in 5.5 knots of wind

Parasailor

The major attraction of the Parasailor is that it acts both as a classic tri-radial spinnaker and also doubles up as an asymmetric.

Its main features are the wide slot that runs from side to side about one third down from the top, and a wing below the slot, on the forward side of the sail.

Once up and poled out, the slot and wing help the Parasailor stay full even in light winds. I have used it in as little as 5 knots of true wind, and every time it looked like collapsing the back pressure exerted by the slot and wing kept it full.

It is in strong winds, however, that the Parasailor comes into its own. Normally I drop the spinnaker when the true wind reaches 15 knots.

On one occasion, on the way from New Zealand to New Caledonia on Aventura III, when I saw a squall approaching, I decided to leave it up and see what happened.

From 15 knots the wind went up and up and settled at 27 knots. Aventura took it all in her stride, accelerated to 9, then 10 knots and once, when it caught the right wave, surged to 14 knots.

Meanwhile the Parasailor behaved as normally as before, the wing streaming ahead and the slot wide open almost visibly spilling the wind.

Boom brake

A boom brake was another useful feature on my boats, as it prevented major damage in an involuntary gybe – as I experienced on three separate occasions. The most memorable happened on the southbound passage from Greenland, after having abandoned the attempt to transit the Northwest Passage from east to west.

All the crew had left us in Nuuk, with the exception of my daughter, Doina. The north-west winds with gusts over 40 produced some nasty seas while sailing across an area of banks with depths of 30-40m.

We were broad reaching with three reefs in the mainsail, no foresail, and the centreboard fully up, a combination I’d used in similar conditions in the past. Aventura IV was taking it well, occasionally surfing at 10-12 knots.

A boom brake will prevent an accidental gybe

Everything seemed under control until a large wave broke violently over us, throwing us into a gybe. The shock was not too violent, as the boom brake controlled the swing of the mainsail, but when I reset the autopilot back on course, Doina pointed to the boom, which was hanging down at a strange angle.

The gooseneck fitting was broken but the boom was still held up by the mainsail and reefing lines. Apart from the broken casting, the boom itself was undamaged. I secured the boom with two lines to the mast winches and we continued sailing like that.

We completed the 1,100-mile passage to St John’s in Newfoundland in seven days without any further problems. A local workshop manufactured a new fitting, this time machined of solid aluminium.

Aventura III with only reefed mainsail on passage to NZ

Sailing in strong winds with just the mainsail is something I discovered by chance while crossing the Bay of Biscay on Aventura II’s maiden voyage. With the northerly wind gradually increasing I tried to furl the mainsail into the mast, but the furling gear jammed and wouldn’t budge.

The only solution was to put a knife to the expensive sail – something I was reluctant to do – or continue sailing like that. Sailing with a full mainsail and no jib in winds often gusting at over 30 knots was certainly exhilarating.

We made it safely into Lisbon where the fault was diagnosed at the top end of the furling gear, which was easily fixed. It never happened again. Another adrenaline-spiked passage was across the Tasman Sea from Fiji to New Zealand on Aventura III.

Happy landfall after a challenging passage: Doina and Jimmy in St John’s, Newfoundland

A low caught up with us bringing favourable but increasingly strong north-west winds. Because of the uncomfortable swell, Gwenda spent much of the time in her bunk.

Earlier in the trip, when the winds were lighter, I’d left the steering to the windvane, but when the wind got stronger and there was a risk of gybing, I preferred to put my trust in the autopilot.

The worst drawback of a full batten mainsail is the difficulty of dropping it even in moderate following winds, as the sail is pushed against the spreaders and the battens tend to get caught in the rigging.

Connected directly to the vane, the pilot mimics the wind to keep the boat on course

Usually I prefer to keep the full mainsail as long as possible but when the wind gets over 30 knots, I furl up the foresail and continue sailing with the deeply reefed mainsail.

This may sound like a rather unusual way of sailing, and it may not suit some boats, but Aventura coped well with it, and I got used to it.

Every now and again I disengaged the autopilot and steered for a few minutes, enjoying the boat surfing down the waves, with the speedometer rarely going below 10 knots.

At one point, Gwenda put her head through the hatch and, as she later told me, saw me standing at the wheel with a huge grin on my face.

“You are absolutely crazy,” was all she said before going back to her bunk. She repeated those words more colourfully later, when the weather had calmed down.

Essential backups

The dual steering system on the first Aventura taught me the importance of having backups for all essential items. We always had two tenders, a smaller and a larger inflatable dinghy. The former could be quickly inflated and was easy to row, while the latter was used on longer trips.

On Aventura III we had two outboard motors, a 5hp and a 2.5hp backup, which we always took with us when we went on longer forays in Antarctica and Alaska.

Communications followed the same pattern: Aventura II had Inmarsat C for text and SSB radio for voice. Aventura III had a similar system, with an Iridium satphone added.

Aventura IV had an Iridium Pilot broadband, which allowed us to download the daily ice charts for the Northwest Passage, as well as sending and receiving large files and photographs.

Aventura Zero had the more advanced Iridium Certus broadband. An Iridium satphone was an emergency backup on all recent boats and was a very useful, cheaper stand-in for the more sophisticated systems.

However, I believe that the most important backup, especially on a short-handed boat, is a second automatic pilot. We didn’t have one on the first Aventura because they were not available in those days but we had a reliable Aries self-steering gear.

I hate to look back now at the countless hours spent at the wheel when there was no wind and we had to motor. On Aventura II we had both a Hydrovane gear and a small automatic pilot, while Aventura III had a Windpilot, a built-in automatic pilot as well as a backup tiller pilot.

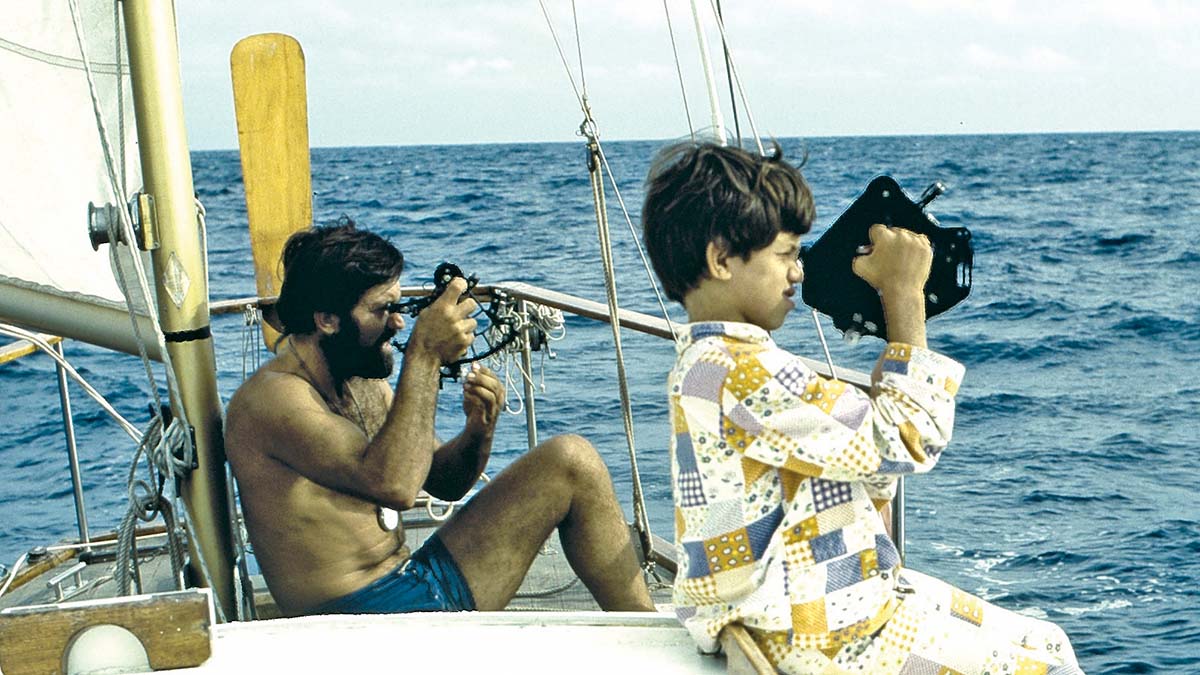

The latter proved its worth when the main unit broke down on the passage with my son, Ivan, from Hawaii to Alaska. As we crossed the North Pacific High we were becalmed in thick fog and surrounded by fishing trawlers.

We had to keep watch permanently on radar while Mickey (from Mickey Mouse) kept the boat on course. Aventura IV had two entirely independent B&G autopilots, which we used intermittently to ensure that both were in working order.

Aventura Zero had a most sophisticated emergency backup to the standard B&G top-of-the-range autopilot. To be protected in case of a lightning strike, the system was insulated from the rest of the boat. It included an autopilot processor, ram and rudder sensor, Triton display unit, GPS and wireless wind sensor.

An emergency 1,200Ah battery, charged by a Sail-Gen hydro-generator, could supply electricity to the autopilot and backup instruments plus the service and propulsion batteries if necessary. It was the ultimate belt and braces concept, and a close match to my cautious mindset.

Why not subscribe today?

This feature appeared in the May 2023 edition of Practical Boat Owner. For more articles like this, including DIY, money-saving advice, great boat projects, expert tips and ways to improve your boat’s performance, take out a magazine subscription to Britain’s best-selling boating magazine.

Subscribe, or make a gift for someone else, and you’ll always save at least 30% compared to newsstand prices.

See the latest PBO subscription deals on magazinesdirect.com