Stephen Wallace demonstrates how he went about removing, resealing and reinstalling the windows on his 25-year-old Sadler 32

Leaking windows, drips and dampness are not fun on a boat: children complain, ‘other-halves’ become potentially mutinous and life becomes generally unpleasant every time it rains. Dampness pervades, and token attempts to put off the inevitable eventually expire in their effectiveness. Having tried silicone sealant, Captain Tolley’s and other alchemistic remedies, the plain facts become clear: the butyl sealant has irreparably broken down, and it’s time to reseal the windows properly.

Our Sadler 32 is now 25 years old. Having initially tried quick fixes, we found that they may buy you a season or two, but resealing the glass and re-bedding the frame is the only real answer. When we eventually cleaned out the frames prior to resealing the glazing, we found the old butyl to be completely shot, ranging in texture from mainly flexible rubber at the top of the window to hard black and porous Crunchie-bar texture at the bottom.

Good value

We’ve now discovered the considerable length of time it takes to remove, disassemble and clean the frames and glass, insert the glazing butyl with sufficient pressure and finish/cure them – all in all, about 10 days. I’d heard good reports about Eagle Boat Windows, so I contacted them for advice on materials and details of how to do the work properly.

(Their alternative service of professional resealing on behalf of owners is extremely time- and cost-effective, enabling you to concentrate on the removal and reinstallation of the windows.) We ordered a kit from Eagle which included glazing primer and 2kg of two-pack butyl glazing sealant, two tubes of Arbomast BR butyl sealant to bed the frames, gloves, rubber chocking for the glass, scourer pads and a small plastic tool – all for just over £80 including p&p, which seemed good value.

Tools for the job

The Eagle Windows kit (gloves and chocking rubber not shown)

The removed windows, and the tools used in their removal

Removing the window frames from the boat

The window frames on our Sadler 32 were very well stuck in with silicone, so our somewhat painful experience removing them may be a great deal less arduous for you if you decide to tackle the same job.

You’ll need a screwdriver, lots of stripping/filler knives with good spring steel (enabling them to bend), sharp Stanley knife blades/similar craft knives, blue (14-day) masking tape and some duct tape.

On the outside of the boat, use blue masking tape to individually mark each frame component and glazing pane with the window number, orientation and whether it’s left or right (ie 6L↑). It seems obvious, but when everything comes apart this is all you’ll have available to ensure accurate reassembly.

The frame components individually marked up with masking tape, which will stick when wet

Our window frame section is a small ‘h’, with the upright of the ‘h’ forming the flange against the boat – this is normally the only part bonding the frame to the boat. Unfortunately ours had been bedded both on the flange and also the ‘reveal’ return into the boat, against internal GRP surround mouldings. To make matters worse, the bedding was silicone rather than butyl sealant, making the frames seemingly impossible to shift.

The ‘h’ section of the window frame

The good news was that the frames were held in by self-tapping screws rather than inter-screws, so as they were removed they went into individually-labelled clean hummus pots, as did later components.

To remove the frame I first carefully cut the silicone sealant internally with sharp blades at the window/GRP frame moulding interface, some areas being too tight to reach at this stage. Then I went around the exterior of the frame edge with both narrow and wide stripping/filler knives, progressively cutting into the silicone. Initially this cut was to a very shallow perimeter depth, but became progressively deeper as I worked around the frame.

Several scrapers were used in tandem and leapfrogged around the frame

The process is basically one of attrition, alternately cutting around the frame from inside and then outside. There comes a point when you can get the stripping knife into a gap and, using a light mallet, can carefully cut all the way through to the frame, progressing all around. Greater speed can be achieved by leapfrogging the most effective filler knives (often narrow and thin-bladed) and leaving several others in their place progressively around the frame perimeter, gently breaking the seal with the hull.

By rigging up a couple of 200mm pieces of duct tape outside the boat in a small loop from hull to window frame I was able to increasingly move the window frame, but avoided a nasty crash when the windows eventually popped out after gently pressing the frame from inside the boat!

A duct tape ‘loop’ saved a resounding crash as the window popped out!

The boat hull can be made watertight by using polythene sheet held in place by duct tape, which is messy to remove, or blue masking tape (which is better) to create temporary glazing. If you’re doing the work at home, take some old dust sheets to wrap the frames in for safe transportation.

In terms of time taken, our first batch of three windows on the port side took a day, and a lot of sweat, to remove. The silicone was tenacious, and at times I wondered whether the frames would come out at all. This experience enabled the second batch of three to be removed in about five hours, so overall you could say frame removal is a two-day job. Yours will hopefully come out a lot more easily if they have butyl frame sealant and are not stuck on the ‘reveal’ as ours were.

Top tip

It’s very easy to damage the external hull GRP surround to the frame by being overenthusiastic with the filler knives. Use a couple of pieces of masking tape on the knife itself about 2cm back from the blade edge, or mask the hull with tape to act as a sacrificial layer.

Dismantling and cleaning the window frames

Make sure you have screwdrivers, plastic scrapers, gloves, snipe-nosed pliers, blades, a butyl kit, a suitably prepared work surface, hot soapy water, white spirit and a piece of wallpaper to hand!

Before dismantling anything, lay all frames face-down on a piece of wallpaper and stencil around them. Mark the stencil with orientation and window number. Note the difference in width between the stencil line and the frame itself. When you eventually reassemble them you will then have an accurate guide to the original width, enabling any necessary light clamping to realign them while the butyl is fresh, ensuring accurate alignment of screw holes when remounting back onto the hull. This is particularly important for larger frames.

Stencilling the frames with orientation and frame number

For the next stage you’ll need screwdrivers, plastic scrapers, gloves, snipe-nosed pliers, blades, butyl kit and work surface protection. White spirit and meths now became our best friend: they are very effective. White spirit and paraffin will not dissolve cured silicone, but once most of the sealant has been removed with a blade they will soften the remaining residue, making it more susceptible to removal with a blade/plastic scraper.

With the frames now free of the boat, the real work began: cleaning and disassembling them prior to resealing the glazing. Our aim was to ensure all surfaces were clean and free of oil/silicone so that the primer and butyl sealant could bond properly to both frame and glass. Cut into the butyl all around the frame perimeter on both sides with a new Stanley knife blade. The butyl may be very hard, so white spirit can help soften it. Do this several times to full depth so the glass is released from the frame.

Cutting into the old butyl with a sharp blade

Our channelled frames were in two halves held together by fishplates – thin strips of metal located in the bed of the channel held by screws through the frame. These need to be released to get the frame apart. After mounting the frames in a workbench, the fishplate screws need to be removed from at least one side – not necessarily easy as a result of the unholy marriage of stainless steel screws and aluminium frames!

Take care not to damage the anodising, distort the frame or break the glass when clamping, so use an old cloth for protection. Carefully clamping the frame enables you to get real pressure and turning force on the screwdriver without the head jumping. Pre-treatment with penetrating oil and hot water may help to dissolve the salt/oxide build-up and expand the aluminium.

Separating the frame halves which were held together by fishplates

Next we separate the two frame halves. Clamp just one end of the frame, so the other end is free to move. Wrap a piece of strong, thin material (eg polyester) around the end of a preferably rounded filler knife, then insert this between the frame and glass at the end of the frame. Using a mallet, gently knock the two halves apart, taking care not to distort anything.

To clean out the frame channel use an old, long, narrow screwdriver to dig out the old butyl, then plastic scrapers and finally a Scotchbrite pad together with plenty of white spirit. Clean the glass and its edges. As our frame progressively became cleaner I used a combination of washing in hot soapy water, Cif, white spirit and finally meths to ensure a clean surface. I also tried using a chemical that is supposed to dissolve cured silicone, but in my experience it was either totally ineffective or had an effect of about 1 out of 10.

The hull window opening needs to be as clean as the window frames, so I used a variety of tools and several home-made perspex scrapers (which proved invaluable as they didn’t scratch) in conjunction with white spirit and Cif.

Cleaning the glass and edge using hot soapy water, white spirit and Cif

Resealing the glazing into the frames

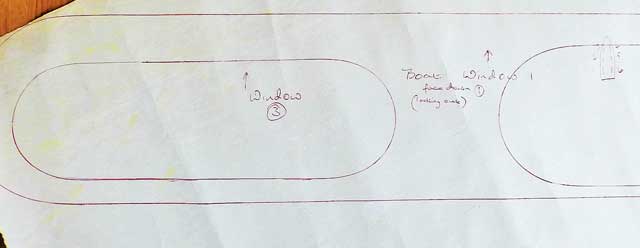

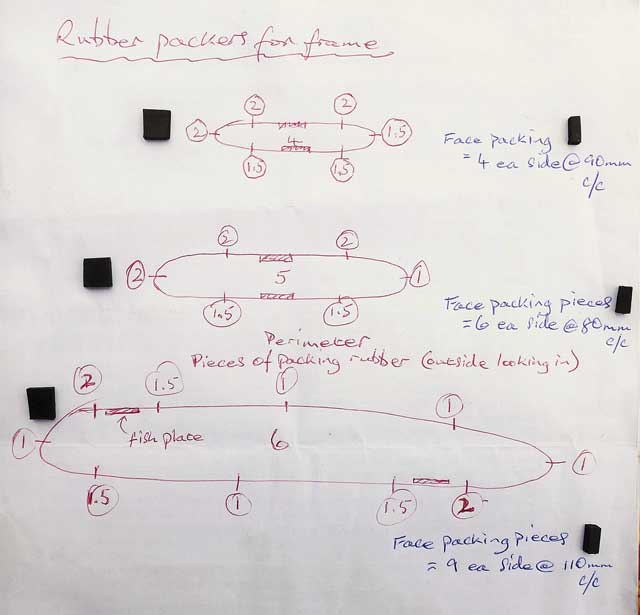

Starting now with chemically clean frames and windows, it’s time to start reassembling everything. Drawing a quick ‘chocking’ diagram for each frame may well prove invaluable as a reference source

As a dry-run, first reassemble the glass into the frames with the fishplates fixed on one side only, and determine how much channel-chocking rubber is needed by inserting it into the frame channel base around the glass perimeter to provide about 1-2mm of movement of the glass within the frame. This may take several attempts, and is likely to involve either single or double thicknesses of rubber: ensure they are cut generously to hold themselves tightly in place.

Inserting the chocking rubbers into the channel

For the channel-base perimeter chocking rubber, cut the rubber strip into 8-10mm-wide blocks the (tight) width of the channel and about 1cm long, using a caliper depth gauge as a template guide to ensure lengths are accurate. Fit to the frame as necessary. Check against your stencil of the original frame size and make sure any cramping leaves some movement.

Try to ensure the glass is central and clear of the fishplates. I drew a quick ‘chocking’ diagram for each frame, which proved a useful reference when one or two of the earlier frame chocks dropped out during handling before application of the butyl. When satisfied with the fit, do a final assembly by putting some butyl sealant bedding compound onto the cleaned fishplates and mitre joints then screwing together. The frame can be left overnight, then cleaned up with a blade dipped in white spirit.

A fishplate covered in sealant, prior to assembling a frame

For the internal glass face chocking rubber, cut short lengths of rubber about 5mm wide and the depth of the channel less about 4-5mm, so when the glass is inserted it will be supported in its internal vertical face but have sufficient ‘cover’ of butyl glazing sealant. I added the number of chocks per side and spacing to the chocking diagram: a useful guide later when inserting the butyl.

We drew a rubber chocking piece diagram for the glass and frames

Use a small (say ½in) brush to apply primer to the inside and outside faces of the frame/glass interface, then set aside for over 30 minutes (but less than 8 hours) prior to filling the frame with two-pack butyl. This butyl has one black and one white component, in our case 1kg each. The white is like a dryish putty and can be cut easily, but the black component is rubbery and deforms before it cuts. I therefore found it easier to measure these by weight before mixing. Wearing gloves, mix these stiff components in equal quantities by twisting and kneading until the marbling becomes a consistent black colour: no need to rush, it cures in days rather than hours.

Lay the frame down with the outside face up and firmly insert the butyl into the frame, using a strong rotating action to maximise pressure until it can be seen filling the bottom channel of the frame. Clean off the excess. Turn the frame over, face down, and carefully press the glass down to create a new void all around the frame into which the internal vertical face chocking rubber is inserted at intervals of roughly 75-125mm. These are pressed in below the frame edge but still support the glass: make sure they don’t rotate by using a flat rather than rounded pushing tool.

If you have done the ‘face-up’ butyl filling properly these will bed into the butyl at the bottom of the channel. Now force butyl into this side, working around the frame and taking care not to create voids, then chamfer/radius the edges to lap the frame using any convenient tool or knife (clean-up is done some days later). Turn the frame over and chamfer/radius the face-side butyl.

While the butyl is fresh, check the frame dimensions against the stencil of the original frame and cramp if necessary. Set the frames to cure, undisturbed, in a warm place for at least a week before cleaning with a soft cloth and white spirit.

Filling the face side with two-pack butyl, using a strong rotating action

Pressing the glass down created a new void all around the frame

Smoothing a radius into the butyl edges with a knife

The frame was cramped to the original dimensions on the stencil

Bedding the refurbished frames back into the boat

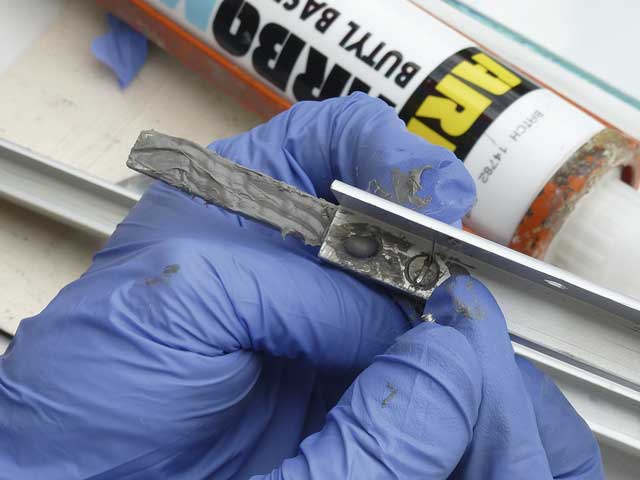

Finally, the frames are re-bedded back into the boat hull. We prepared each frame for installation using one-pack butyl sealant, which is essentially non-setting and can be cleaned up easily with white spirit.

First, check the fit of the window and alignment of screw holes in the hull opening: thankfully all our screw holes lined up correctly.

The frames were inserted to check fit and hole alignment

Despite our careful stencilling, some of the hull window openings still needed a couple of mm of easing to enable the frames to fit back in. I therefore made a small tool to hold abrasive sheet from

a 10cm block of wood and some old aluminium tile trim, which happened to be the same depth as the frame. Any additional making-good of the opening was also carried out at this stage.

An ‘easing’ tool, about 10cm long, adjusted the hull window aperture

Our windows have a slight curvature, which immediately straightens when you remove the frame from the boat. There is therefore a tendency for the central section to be compressed, squeezing out any sealant and potentially giving rise to future leaks. This didn’t seem an attractive proposition after all the hard work, so to avoid this I decided to incorporate small rubber spacers made of some Firestone EPDM roofing material I had been given. It was just over 1mm thick and was bedded in the same butyl sealant a day in advance of installation. Note that this is a non-standard procedure: however, reading the PBO forum, some other people feel spacers are desirable.

Thin EPDM sheet roofing packers (bedded in butyl) were used to avoid butyl sealant squeeze-out

Each frame was prepared for installation using Arbomast BR (one-pack) butyl sealant. This versatile material is intended for ‘covered’ sealing applications and is essentially non-setting, apart from an external skin which forms to a stiff chewing-gum-like consistency after a day or so. It cleans up easily with white spirit.

Cut the butyl nozzle at 45° and apply a 6mm bead of bedding compound on the inside of the window flange in line with the screw holes, forming a doughnut shape around the screw holes themselves. Use a little more if incorporating spacers.

A 6-7mm sealant bead was applied in line with the screw holes, forming a doughnut shape around the holes themselves

Present the window to the hull the right way up and gently press it against the hull, which will create a ‘witness’ around the perimeter. Remove any initial sealant appearing in screw holes in the frame before the screws are inserted, otherwise a hydraulic build-up of pressure in blind-ended holes or inter-screws can occur. However, you may also wish to put a little sealant around the neck of the screw to ensure an effective seal. Carefully tighten the screws, working around the perimeter of the frame, doing this in rotation several times until only a small gap remains between hull and frame. The butyl should not be squeezed out completely or it will leak. Screws should only be ‘nipped up’, not fully tightened. Leave for a few days to harden, then trim using a scraper and white spirit.

So that’s that job complete. It took longer than expected, but will hopefully mean we’re watertight for another 25 years. Now, let’s see about re-bedding the hatch!

Lessons Learned

1: Window refurbishment is a lengthy and labour-intensive job taking around 10 days (excluding curing time) for six windows: just cleaning the frames took two days.

2: Use a professional resealing company’s services if time is tight; this then enables you to concentrate on removal/reinstallation.

3: The two types of butyl were pleasant but messy to work with – prepare!

4: Your technique will improve as you do more windows, so do the job in a couple of batches.

5: There’s more to this job than meets the eye, but it’s well within the capabilities of a practical boat owner!