Ben Lowings talks to Bjorn Haraldsson about his simple air-regulated keel

Anyone who has wended their way through a commercial anchorage cannot fail to have seen the cataracts of water expunged from openings high up on the flanks of tankers and bulk carriers.

This is, of course, ballast water.

It is primarily used to balance a hull against the varied weight of cargo, to keep a massive ship appropriately heavy and low in the water. It’s also been used in small fishing boats.

A box amidships – open at the bottom – balances the boat and also holds the day’s catch in a seawater well.

It’s perhaps because of this association with slower, working vessels that the ballast water idea is not popular in larger yachts, where speed is almost always a consideration.

It is to be found in the trailer-sailer market; Swallow Yachts is one of the most notable boatbuilders to use this system.

Bjorn uses Skarwen for cruising home waters. Credit: Bjorn Haraldsson

Björn Haraldsson is a Swedish sailor with three Atlantic crossings under his belt, and a Mediterranean tour in Snowflake, a self-built Folkboat.

He has applied his inventive skills to scale down the ballast water concept for a small sailing boat with the help of little more than a typical air pump.

His Skarwen (‘Cormorant’ in Swedish) cruises local waters with three ballast water compartments and where the centre of gravity and righting moment can be adjusted by virtue of a self-designed pneumatic keel.

How does this air-regulated keel work?

Well, when wishing to lighten the keel, rather than draining out the water, driving it out using the pressure of an air pump is relatively quick and easy.

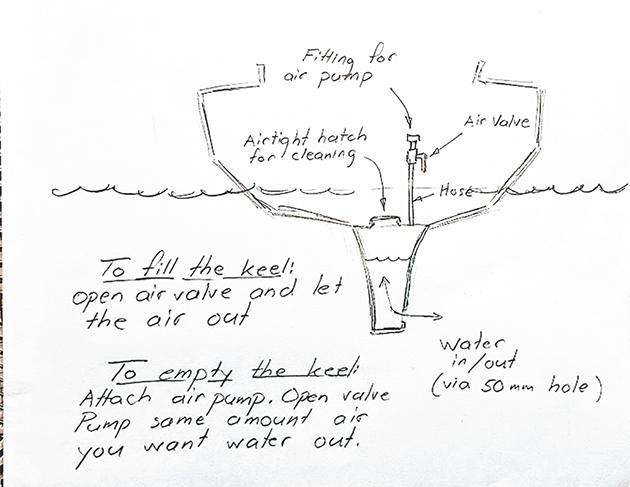

Haraldsson’s sketch (below) shows how Skarwen empties a ballast compartment by the crew attaching the portable pump to the hull fitting, opening the valve, and pumping the water out.

The keel is easy to regulate, as Björn’s sketch shows. Credit: Bjorn Haraldsson

To fill one ballast compartment you simply open the valve.

“I drew a boat inspired by Swedish, double-ended working boats, called Kullasnipa,” Haraldsson explains. “First I made a model at [a scale of] 1:10… with a system of air-regulated ballast tanks.”

He filled up the tanks with different amounts of ballast water and then saw what happened when placing a ‘crew’ (in this case a carrot and a potato) on the rail, as a way of examining the righting moment.

It’s not possible to recreate a high wind or any sort of sea state in a wheelbarrow in a back garden, but a laudable simulation was achieved.

Recreating the angle of heel was done with a line from the hounds to a block on a vertical stick, from which was suspended a plastic bottle he could fill from a watering can.

The righting moment was then measured by an inclinometer placed at the mast.

The system of air-regulated ballast tanks: at the base of each compartment, were three permanently open holes of 50mm diameter for filling and drainage. Credit: Bjorn Haraldsson

Lifting the model from the wheelbarrow ‘pond’ in both hands, ballast water cascaded from three pin-prick holes in the base of the little keel.

Backyard testing was a real success: It was easy to imagine now how to scale it up.

“When I showed my drawings, the model and the results of the tank tests to my friends at the boatyard, they immediately wanted to start building.”

With his enthusiastic friends, he began a busy voluntary works programme.

“We were [at] the construction two days a week for two years,” Haraldsson writes. “Hull, deck, hollow wooden mast, spars, stainless fittings, etc… We started by putting up cross-section [support] frames for a slim 6.2m-long double ender.”

The hull is 4mm-thick marine plywood, sandwiched between 2.5mm GRP, glassed with 1.5mm-thick GRP within.

Friends helped Bjorn build the boat. Credit: Bjorn Haraldsson

In the designer’s opinion, this strength combined with lightness meant internal frames and stringers were redundant. Single laminate GRP was used for the keel.

They used what they felt was the more waterproof and sticky isopolyester as opposed to orthopolyester. Tanks and deck were laminated to the hull to avoid piercing the construction sandwich.

“Without the water ballast, the boat weighs approximately 500kg,” Haraldsson confirms.

Skarwen’s design accommodated three glassed-in ballast water compartments; the aftermost 40lt, midships 250lt and the foremost 60lt making a total of 350kg of ballast.

The keel voids were funnel-shaped in a cross-section.

At the base of each compartment, were three permanently open holes of 50mm diameter for filling and drainage.

On the upper side, central on the deck, each was fitted with a water and air-tight screw fit plastic inspection hatch.

Ordinary plastic hose from each section leads to a valve, then to a pump fitting.

Aside from the three units of pneumatic keel, Haraldsson’s team also built a well for a 6hp outboard motor.

Opening the air valve allows the water to flow out of each ballast tank. Credit: Bjorn Haraldsson

“The propeller [sits] just in front of the rudder,” he adds. “We also sewed sails from old sails.”

Skarwen took to her home waters with alacrity. Crew members were invited to move about the boat to establish comfortably balanced heel at each point of sail.

Ballast water was duly expelled with a wide cylinder pump of the same kind popularly used to inflate a tender or stand-up paddleboard.

Haraldsson says his pump operates at comparatively low pressure (‘of the order of 0.1 bar’) though it’s as well to note SUP pumps can go up to at least 1 bar (15psi).

“It’s so easy to push the water out because the pressure is low and depends on the height difference between the water surface in the tank and that outside. Say the difference between the water surface inside and outside is 30cm (it varies between 10cm and a maximum 70cm) the pressure will then be 0.03kg/cm2, which is more than 100 times less than in a regular bicycle tyre. Not bad.

“It took only five minutes to pump out 250lt of water,” says Haraldsson.

While not instant, this is an impressive clearance rate.

In practice going from full to empty would rarely be a single operation, but rather calibrated to adjust to the eternally-varying wind strength and the whole basket of other physical variables which lie right at the heart of the enjoyment of sailing.

The fore and aft tanks were principally filled and emptied to trim the boat along the pitching axis.

This would be assessed beforehand depending on the number of crew and wind strength.

Lifting out to a trailer was less onerous than might have been imagined when the boat was underway in her most laden state.

“When the boat is taken out of the water on a slip or pulled up on a beach, you simply open an air valve and the water flows out as the boat leaves the water.”

Each ballast water compartment has a plastic inspection hatch. Credit: Bjorn Haraldsson

Haraldsson notes the Swedish boatbuilders of modern times have been focussed on large GRP cruising boats, rather than trailer-sailers or smaller boats.

There’s no Swedish equivalent of the Cornish Crabber, he adds.

Scandinavian inventors, he argues, admire the culture of resourcefulness and experimentation fostered in the UK and especially by magazines such as PBO.

“Lightening the boat as you go,” he explains, “is so much more flexible than carrying iron bars as ballast deadweight. All sailors will know that the ratio between sail area and the boat’s displacement is an important factor when it comes to giving a boat good speed. Now it is possible to easily reduce the boat’s displacement by up to 40%, without having to throw lead bars or crew members overboard!”

So how does the Skarwen pneumatic keel fare, now in her second year in the water?

Well, Haraldsson says the vessel is actually “stiffer than we hoped”.

So he’s gone for more sail, a spritsail main and staysail. What would be a jib on, say, a Crabber is a genoa whose clew extends just abaft the mast.

Haraldsson shares this project with PBO readers in the spirit of innovation, and the work continues: he has just fashioned a jackyard topsail and has sewed the appropriate canvas to go with it.

How to repair keel band corrosion on small boats

Galvanic corrosion is often something mainly associated with metal fittings on larger craft: however, David Parker has a cautionary tale…

Keel types and how they affect performance

Peter Poland looks at the history of keel design and how the different types affect performance

The things I learned when the keel fell off

Photo: Enya being lifted out to inspect the swing keel Sailing is full of compromises and boats with swing keels are…

How to check keel bolts

Colin Brown describes a series of checks you can carry out to assess the structural integrity of the bolts which…

Want to read more practical articles like this?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter