The wreck is likely to be the Holigost, the 600-year old ship that sailed to France as part of Henry V's war fleet

Historic England is taking steps to protect and investigate a shipwreck in Hampshire that is believed to be the second of four ‘great ships’ built for Henry V’s royal fleet.

Experts from Historic England believe the wreck that lies buried in mud in the River Hamble near Southampton, is the Holigost (Holy Ghost). The Holigost was a major part of Henry V’s war machine, playing a key role in the two battles that broke French naval power and enabled Henry to conquer France in the early 15th century.

The Holigost joined the royal fleet on 17 November 1415 and took part in operations between 1416 and 1420, including two of the most significant naval battles of the Hundred Years War. It served as the flagship of the Duke of Bedford at the battle of Harfleur in 1416, suffering serious damage, and was in the thick of the fighting off the Chef de Caux in 1417.

It was rebuilt from a large Spanish ship called the Santa Clara that was captured in late 1413 or early 1414, then acquired by the English Crown. The name of the ship is derived from Henry V’s personal devotion to the Holy Trinity.

The find

The find was made by Dr Ian Friel, historian and an expert adviser to Historic England when he worked for the former Archaeological Research Centre. He was re-visiting documentary evidence for his new book, Henry V’s Navy and brought his findings to Historic England.

It looks at the men, ships and operations of Henry’s sea war, and tells the dramatic and bloody story of the naval conflict, which at times came close to humiliating defeat for the English.

Friel said: ‘I am utterly delighted that Historic England is assessing the site for protection and undertaking further study. In my opinion, further research leading to the rediscovery of the Holigost would be even more important than the identification of the Grace Dieu in the 1930s. The Holigost fought in two of the most significant naval battles of the Hundred Years War, battles that opened the way for the English conquest of northern France.’

Duncan Wilson, Chief Executive of Historic England (formerly known as English Heritage), which is now beginning further research and assessing the boat for protection said: ‘The Battle of Agincourt is one of those historic events that has acquired huge national significance.

‘To investigate a ship from this period close to the six hundredth anniversary is immensely exciting. It holds the possibility of fascinating revelations in the months and years to come. Historic England is committed to realising the full potential of the find.’

The ship had a crew of 200 sailors in 1416, but also carried large numbers of soldiers to war, as many as 240 in one patrol. Conditions aboard must have been crowded and unpleasant, and that was before they got into battle.

The ship carried seven cannon (guns were not so important in sea war then), but also bows and arrows, poleaxes and spears, along with 102 ‘gads’ – fearsome iron spears thrown from the topcastle that could easily penetrate the body armour of the period.

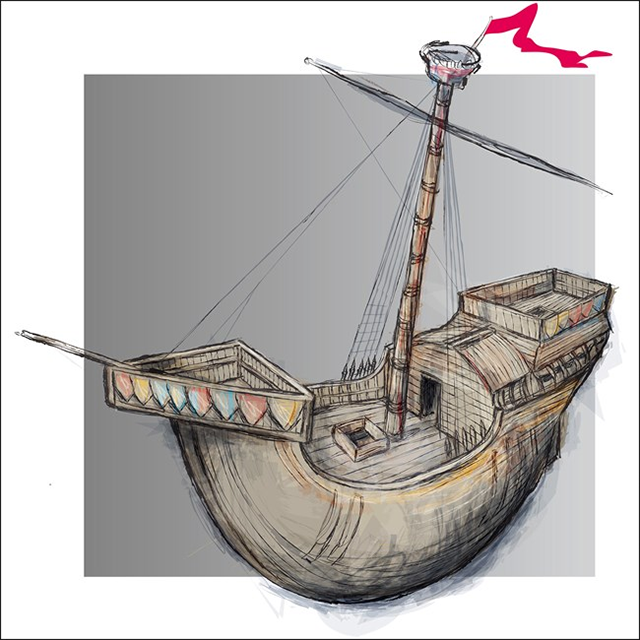

If verified, the Holigost would be a tangible link with the life and times of Henry V. Like all the great ships, it was built to further Henry’s war aims, but its decoration and flags also reflected both his personal religious devotion and his political ideas. Unusually, this included a French motto Une sanz pluis, ‘One and no more’, which meant that the king alone should be master.

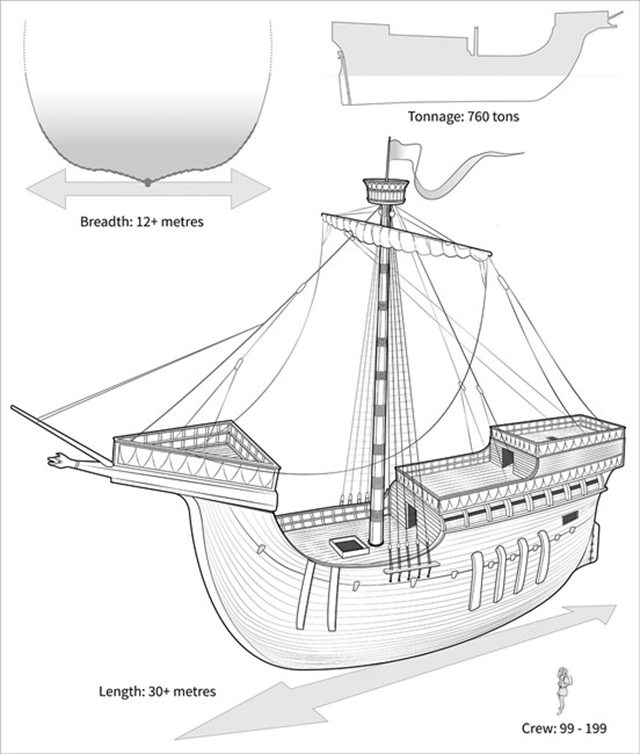

The ship was a clinker-built (using overlapping planks of timber) of around 740-760 tons. Despite huge expenditure on maintenance work, the Holigost began to succumb to leaks and timber decay.

In 1423 a ‘dyver’ named Davy Owen, probably a Welshman, was employed to dive under the ship to stop up cracks, perhaps, the earliest-known instance in England of a diver being used in ship repair.

Related articles

- Diver jailed for fraud following historic canons discovery

- Anchoring is allowed in Osborne Bay

- Divers made to pay £63,500 for undeclared shipwreck raids

- Shipwrecked mariner rewarded 30 years late

Future scientific research on the ship could reveal much about late medieval ship design and construction, both in England and Spain. The wreck might also improve current understanding of life aboard ship, ship-handling and naval warfare in the 15th century.

Given the care with which the ship was laid up, the site itself might also preserve information about contemporary dock-building and docking practices. Historic England experts use a range of research methods, including sonar, remote sensing including aerial imaging using drones, and dendrochronology.

The remains of the largest of the four ships, the Grace Dieu, were identified in the river Hamble in the 1930s and have been protected since 1974.

Aerial clue

Dr Friel first spotted the wreck site on an English Heritage aerial photograph of the Bursledon stretch of the river Hamble when he worked in the former Archaeological Research Centre (ARC) at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

He made the connection with documentary evidence that Henry V’s Holigost had been laid up there. Subsequent probing of the site by ARC revealed the presence of a solid object under the mud of the river Hamble in Hampshire, but no further work was undertaken.

Dr Friel has included the air photo in his new book, Henry V’s Navy and brought the site to the attention of Historic England. Historic England has moved to protect the ship and will soon begin further research.

Ship details

Tonnage (burden): 75-760 tons

No of masts: 1

Crew size: 99-199

Origin: originally the Santa Clara [Saint Claire – of Assisi, an Italian Saint and early follower of Saint Francis of Assisi], a ship belonging to the Queen of Spain; captured late 1413/early 1414 by one of William Soper’s ships [Soper was one of Henry V’s key admin men]; rebuilt 1414-15 as the Holigost

Disposal: docked at Burseldon (Hamble) in 1426; last mentioned in records 1447-52

Summary: only ever used in war operations; participated in Earl of Dorset’s expedition to the Seine (1416), the battles of 1416 (off Harfleur) and 1417 (in the Bay of the Seine) (the ship was damaged in both), and the Earl of Devon’s seakeeping voyage of 1420. Varying tonnage figures due to the addition of upperworks for specific expeditions