Is blind navigation a foggy notion for Yachtmasters, or a useful seamanship skill? PBO investigates

Blind navigation. Two words that have struck fear into the hearts of countless Yachtmaster candidates – but why?

What’s the point in sending the would-be skipper below to the chart table to navigate, while he or she could probably do it better by eyeballing a few marks ashore?

The usual RYA excuse is that it shows the candidate’s ability to navigate using traditional methods in restricted visibility, but most instructors see it more as a demonstration that their charge fully understands the wealth of information available to them without the aid of electronics, especially positioning systems such as GPS.

Viewed that way, blind navigation could be a useful exercise for any sailor, Yachtmaster candidate or not.

Eschewing satellites

If the GPS goes haywire, what are we left with? These days, the answer is quite a lot: log, speed through the water, depth, wind direction and speed, time, sea

temperature, compass, almanac, charts and, given adequate visibility and proximity, marks ashore.

Take away the visibility and, however tempted one may be to panic, only one of those sources of information has disappeared.

Complete loss of power is more serious as most modern boats will then lose all the above bar the time, compass, charts and almanac – enough for good visibility, but not for bad.

Crossed bearings give a good position fix

For that reason, it’s worth carrying a leadline and some kind of method for assessing distance travelled, be that a Walker log or a log line, or simply practising your ability to accurately estimate speed through the water.

At the other end of the spectrum, radar offers a powerful means of navigation in poor visibility.

Buoys and coastal features stand out well, while bearings and ranges are accurate and swift to take.

Unless your instructor gives marks for ingenuity you probably won’t pass a Yachtmaster blind navigation exercise using radar, but if you have it, take the time to learn to use it for more than just ship spotting: in practice, it’s likely to be your first port of call if the GPS goes wrong.

For this article and the RYA exercise however, we’re just concerned with the loss of GPS on a boat without radar, so let’s take a look at what tools we have and how we can use them.

Tools for blind navigation

Log

A key piece of navigational information since man first ventured away from shore, distance run is only equalled by course in navigational importance.

If you know the distance you have travelled through the water, with the aid of the almanac you can easily adjust it for tide to find out how far you have travelled over the ground.

Speed through the water

Multiply this by time and you get the distance run.

By and large, it’s easier to measure speed than distance, so most traditional methods rely on an accurate means of timing a set period – for many years, the half-minute glass provided this.

Depth

Whether obtained with an echo sounder or a leadline, this is one of the most powerful tools we have for determining position when coastal sailing in poor

visibility.

Charts show accurately plotted contours, usually at 2m, 5m and 10m, which can provide accurate position lines when adjusted for tide.

If you know where you are and a contour will take you where you want to go, that’s all you need to follow – although the route may be a bit circuitous!

Wind direction and speed

Although not generally viewed as a source of navigational data, wind speed and direction can be useful in assessing and allowing for

leeway, as well as for planning your passage to make best use of the breeze.

Fog and wind are not best friends, however, so its usefulness may be limited in practice.

Time

The third element of the distance/speed/time triangle, an accurate means of timing intervals is essential.

For example, in a blind navigation exercise it may be easier to ask the helmsperson to motor at a constant speed for a set time than asking them to cover a specific distance through the water.

Sea temperature

This may not be particularly useful in coastal navigation, but ocean sailors use sea temperature to find the well-charted boundaries between ocean currents,

giving a rare opportunity to obtain a mid-ocean position line.

In coastal waters, outfalls from industrial facilities such as power stations may provide a localised change in sea temperature close to the pipe outlet

Compass

Together with the log, this is your best friend in poor visibility.

We’ve all spent night passages glancing at the compass, and with a careful calculation beforehand, a course-to-steer can result in a remarkably accurate landfall.

For blind navigation close to shore, you’ll need to keep a careful eye on your course to help maintain an accurate estimated position

Almanac

For blind navigation, you’ll need to calculate the tide height where you are.

One way to do it is to check your sounder against a charted mark, which works well for a short exercise, but to sail further you’ll need rates and sets from the

almanac and charted tidal diamonds or a tidal stream atlas.

Charts

Without these you really are lost. Make sure you have detailed charts of the areas in which you sail, and keep them up to date.

In popular waters such as the Solent, racing marks can be useful, well-charted points to aid navigation, but as they are usually named after sponsors some will change their names annually – another reason to update!

Sea bed

Although not listed above, a traditional and effective way to find an approximate position close to shore is to take a sample of the sea bed.

Lead lines usually have a hollow in the base of the weight which can be ‘armed’ with tallow.

This brings up a sample of the sea bed, which can be compared with the chart to help confirm that your calculated position is correct

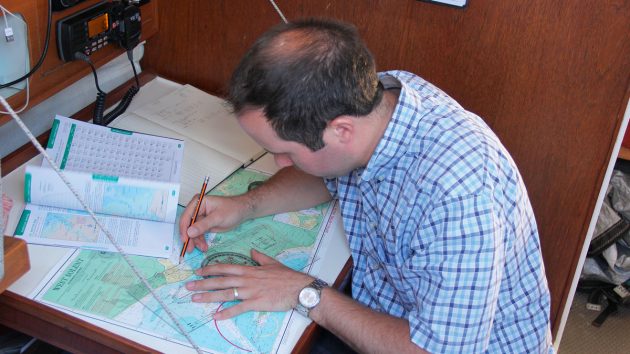

Blind navigation in practice

For a short sail in coastal waters, your depth, compass, speed/log and time are likely to be your primary sources of information.

That’s certainly the case for the RYA exercise – an instructor will expect to see you make good use of depth information and maintain an accurate estimated position (EP).

With regard to the latter, you have a choice: work out an EP by applying a tidal offset to a course that you are already steering or, if you have time, work out a course-to-steer (CTS) beforehand.

A tidal atlas gives a quick way to find the tidal set and rate close to your position

The latter has the advantage that you are less likely to need to make corrections to your course, but if the visibility suddenly closes in or the instructor springs an exercise upon you, you might not have time.

It’s good practice to keep an eye on what the tide is up to, whether or not you expect to navigate blind.

If you pass a charted mark, it’s the work of a second to check your depth sounder against the chart to give you the rise of tide.

Make sure you have noted the high and low water times and heights for the nearest port, and if you have a tidal atlas, mark the times on it to give an at-a-glance reference to the sets and rates through the day.

Finally, keep your log up to date.

A charted position or lat/long scribbled in the log book on a regular basis give a useful starting point for navigating in reduced visibility – an easy point for navigating in reduced visibility – an easy way is to note a time on the chart next to any navigation mark you might pass.

Blind navigation shortcuts

Any chart calculations are likely to be over quite short distances, so the usual EP/CTS methods using an hour of tide can rapidly become unwieldy.

I find a quick way is to work in six-minute intervals, allowing you to quickly divide times, rates and speeds by 10.

For example, a boat sailing at five knots will travel half a mile in six minutes, so to sail a mile will take 12 minutes. If she is being offset by a knot of

tide, then for that mile you’ll need to apply an offset of 0.2 miles.

Calculating a course to steer gives you the opportunity to work out the time you expect to take to cover the distance. That way, the helmsperson and yourself know what to expect and when, any variations give you a chance to get a more accurate idea of what the tide is doing, and you have time to plan for the next leg

When navigating in restricted visibility, the shortest route is not necessarily the best one.

We tried out a blind navigation exercise in the Solent, sailing from Beaulieu entrance to Newtown Creek.

Planning your course to cross contours…

In good weather, you would simply eyeball a course, apply an offset for tide and sail straight there.

For our purposes, however, we found it better to sail west along the coast for a short distance, checking our position using charted marks and depth contours, until we reached a point where we could sail straight across the Solent to another mark just uptide of our destination before following another contour to the creek.

..gives multiple position checks as you sail

This approach had several advantages:

- It ensured that we maintained the best fix possible.

- While sailing along the contours, we were sailing with the tide, so could simply add the rate to our speed through the water.

- For crossing the Solent, the CTS calculation was relatively simple, just requiring an offset for tide across our course.

- Making landfall uptide of your destination gives room to correct your position if your landfall isn’t spot-on.

Going upwind

Tacking is the enemy of an accurate EP, but there are things you can do to minimise the error if you’re forced to beat.

Firstly, make an allowance for leeway. On a beat this will be at its maximum, and will vary according to the wind strength.

Continues below…

Nav in a nutshell: Tacking to clear a headland

Simple step-by-step chartwork can show us when we’ll need to tack to clear a headland, says Dick Everitt.

Nav in a nutshell: When the wind bends

Any number of factors can affect the wind near land on coastal voyages, says Dick Everitt.

Nav in a nutshell: Curved track or straight?

GPS will keep us on the straight and narrow by constantly showing how much we need to adjust our heading…

Nav in a Nutshell: Navigate by ‘feel’ using an echo sounder

The ‘ping’ is king: You can navigate by ‘feel’ over the seabed in adverse conditions by using an echo sounder…

If it’s your own boat, you probably know how much leeway she makes; on a strange boat, ask the skipper if possible, or assess it from the wake.

Secondly, keep everything even. On a dead beat, sailing for the same amount of time on each tack should keep your course through the water directly into the wind.

If there is a making tack, take note of the time sailed on each tack and keep updating your EP. As above, working in six-minute intervals can help here.

Blind navigation: Step by Step

1. It’s likely that the nearest tidal data will be for a secondary port. Start by finding the tide time and height at the reference port…

2…and the time and height differences for the secondary port. Interpolate if the tide lies between Neaps and Springs.

3. Almanacs often have useful tables, or you can draw your own. They’re a handy prompt, especially if you don’t do this often!

4. Finally, use your calculated values on the appropriate tidal curve to show the behaviour of the tide over the next few hours.

Helpful hints for blind navigation

- Check the accuracy of your log and depth sounder.

- Ensure the compass has been swung recently.

- Practise your mental maths and speed distance calculations in advance.

- In a short test, you just need to know the tidal height at that time of day: the easiest way to do this is to check your depth against a known mark on the chart, such as a buoy. Be aware, however, that over a longer period of time you need to adjust your calculations as the tidal heights change.

Enjoyed reading Blind navigation: how to find your way in restricted visibility?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-