GPS is not infallible, so it makes sense to know the basics of shaping a rough ‘course to steer’ on a paper chart, says Dick Everitt.

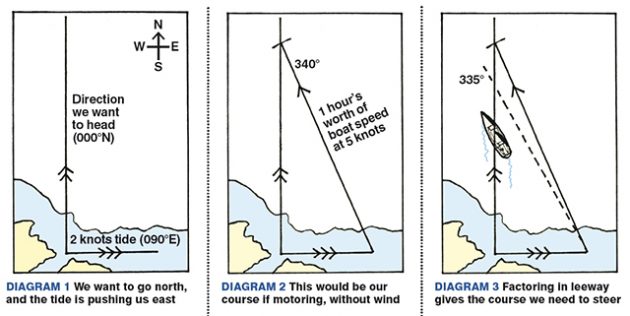

To keep things simple let’s say we want to go north 000° with a boat speed of 5 knots and there’s a 2-knot tide trying to push us to the east 090°.

We draw a long line due north, and at the departure point an hour’s worth of tide due east (see diagram 1).

From the end of the tide line set a pair of compasses to an hour’s worth of boat speed and strike off an arc to cross the vertical line. Connect those two points and our course would be 340°, if we were motoring and there was no wind (diagram 2).

With any wind we have to allow for leeway, which is how much it will blow us sideways (explained in a previous Nav in a nutshell article). Let’s say the wind is blowing with the tide, so we compensate by heading up into the wind another 5°. Our ‘course to steer’ is now 335° (diagram 3).

The RYA teaches navigation chart work in degrees ‘true’ (°T) and then converts to ‘magnetic’ or ‘compass’ at the end. Charted tidal diamonds and bearings, such as leading marks and sector lights etc, are given in degrees true because True North never changes, whereas magnetic variation is shown on the chart to move a bit each year.

But I prefer to work directly in degrees magnetic, because it’s fast and you can forget the old ‘East is least and west is best’ mnemonic for converting from true to magnetic (it reminds you to ‘subtract east variation and add west variation’. If, for example, your true heading is 110° and the variation is 5° west, add 5° to the true heading to get a magnetic heading of 115°).

Working in magnetic allows you to work directly with your ship’s and handbearing compasses, and most GPS units can also be set to work in magnetic.

If you use a Breton Plotter for chart work you can mark the amount of magnetic variation and use that as zero (see photo, how 110°T automatically reads 115°M).

This Nav in a Nutshell was published in the February 2012 issue of PBO. For more useful archive articles explore the PBO copy shop.

Nav in a Nutshell: Clearing bearings

In the first of his series on back-to-basics navigation Dick Everitt explains how to use a few simple lines to…

Nav in a Nutshell: What is a transit and how are they used in navigation

Lining up a pair of appropriate land features or navigation marks can help keep you safe, as Dick Everitt explains

Nav in a Nutshell: Navigate by ‘feel’ using an echo sounder

The ‘ping’ is king: You can navigate by ‘feel’ over the seabed in adverse conditions by using an echo sounder…

Nav in a Nutshell: Lighthouse characteristics on charts

Dick Everitt helps illuminate our understanding of lighthouse characteristics on charts, their dipping distances and loom...

Nav in a nutshell: Navigating at night

There’s no need to be in the dark if your preparation is thorough and easy to understand, says Dick Everitt…

Warning not to use LED bulbs in filament bulb navigation lights

Replacing filament bulbs with white LEDs in tricolour navigational lights could result in vessels not being insured, the Cruising Association…

Nav in a nutshell: Navigate with radar

Dick Everitt gives us a clear picture of the advantages to be gained from using radar to check our navigation

Nav in a nutshell: Looks good on paper

Up-to-date printed paper charts are a good bet for identifying your position – but they do have their limits, says…

Nav in a nutshell: Electronic charts

Dick Everitt assesses the differences between raster and vector charts when deciding on which chart plotter to buy

Nav in a nutshell: Coping with currents

Dick Everitt explains how sailors can apply knowledge of tidal streams to ensure that water flow is a help, not…

Nav in a nutshell: Know tidal vectors

'It’s easy for any sailor to remember how to draw tidal vectors with a handy little aide-mémoire!' Says Dick Everitt.…