John Latham experiences an inauspicious start to his cruise from Dublin to Northern Ireland when hit by gale force winds in harbour...

Following a two-year pause from cruising habits in our Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 349, Scoundrel, we were ready to set sail again.

The hiatus was partly due to me being overseas in Malaysia and also because of the Covid-19 pandemic. We’d enjoyed a very successful cruise to the Scottish Western Isles and the Island of Harris in 2019 so in 2022, co-owner John McQuaid and I decided to head north again, but remain to the western edge of the North Channel.

Tory Island was our goal. We had visited that most remote of our offshore islands in 2018 during our round Ireland voyage but because of impending bad weather reports, we stayed less than 24 hours. Eager to spend more time exploring Tory and also keen to investigate other interesting harbours and anchorages in Donegal, we planned our cruise.

Our preparations included servicing the engine ourselves and having our liferaft and lifejackets serviced. The start date for our cruise was to have been 24 June. However, forecasts for this Friday and the following three days were for strong southerly winds blowing up to Force 7, particularly in the North. We agreed to postpone our departure.

Article continues below…

Man overboard: recovering a casualty from a marina

Rupert Holmes shares top tips on how to avoid the dangers of falling in while in a marina and how…

Learning from experience: Chasing the leak on a sinking boat in Lyme Bay

Dr Brian Johnson became quickly and intimately acquainted with his engine’s silencer when it threatened to sink his Westerly Pageant…

MOB drills

On Friday, not wishing to waste the day, we decided to spend it doing man-overboard (MOB) practice. So, with a blustery southerly wind, we spent some time in Scotsman’s Bay (south of Dun Laoghaire’s East Pier) trying our crash tack and backing the jib technique using a figure of eight to pick-up.

Neither of us was successful on our first attempt which suggests that we should practice this quite often. The following two days were indeed windy, the Dun Laoghaire Regatta was cancelled on Saturday due to a gale.

We left Dun Laoghaire Marina at 0500 on Monday, 27 June, with a westerly Force 4 and a new flood to sweep us around Howth Head and speed our northerly progress. Soon we were east of Lambay Island and doing up to eight knots over the ground on a broad reach.

Rockabill Lighthouse was abeam by 0800 and by midday we were east of Dundalk Bay with the wind dying. Starting the engine, we used its propulsion for the next two hours. Then, with a fresh southerly as forecast, we were running with main and jib. Soon we had to use the MOB drill in earnest – for a throwing line bag that slipped overboard accidentally.

The bag is quite small without a loop or strap for a boat hook to catch, so it required a very uncomfortable stoop under the rail and a hand grab to get it on board. As the wind freshened, we took in the jib and ran with one reef in the mainsail, arriving in Ardglass at 1620, having covered 63.2 miles in 11 hours and 14 minutes.

Historic harbour

Ardglass is an interesting marina tucked into a very old fishing harbour in County Down, north-east of St John’s Point Lighthouse. The harbour is overlooked by a small town with some impressive Victorian architecture. The entrance is between the rocks of Phennick Point to the north and the pier of the fishing harbour with a sharp turn to port after the marina breakwater.

There is a narrow channel that is marked by port and starboard buoys once inside the breakwater. We arrived at low water and as we motored into one of the outer pontoon fingers, we were only feet away from rocks to the north and a rusty green post. The pontoons are anchored with chains rather than fixed to piles; thereby hangs a tale.

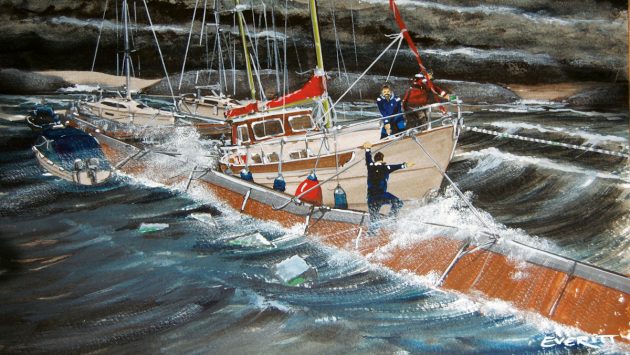

Phennick Point and Ardglass Bay during gale

We woke up to the signs and sounds of a gale building from the south on the Tuesday. By 1100 the wind speed was more than 40 knots and the gusts were stronger. Though sheltered to a great degree by the breakwater and the fishing pier, the marina was subject to some strong gusts.

The main pontoon, linking our berth to the land, runs east to west; unfortunately, a large English motorsailer with high topsides had berthed on the windward side of this overnight.

Listing pontoon

By mid-morning that pontoon was listing seriously to leeward and both breaking up and sinking. The berthed vessel was unable to be pulled off and the pressure was too great.

This pontoon was our only link with the shore, but it was also the structure that attached our pontoon berth to shore; if it completely failed, the whole marina was likely to disintegrate!

DIY outrigger floats, made from wood, rope and plastic barrels, helped keep the ponton afloat

At first, there was no sign of alarm or attention from marina staff, and the skipper of the motorsailer just stood watching. As each minute passed, the decking tipped more towards the vertical and more pieces of concrete float broke off. These had polystyrene adhering to them and were thus floating and drifting.

John and I, plus several crews of yachts on the outer pontoon, began to try to do something. We asked the English skipper if he could pay out an anchor which could be placed to windward and used to haul his boat off the stricken structure. John and another man took his anchor, having traversed the vertical pontoon deck (hoping it would not suddenly capsize completely).

With some difficulty, this anchor was carried forward of the forestays of yachts on an inner pontoon, and thrown into the marina about 30m to windward of the boat. Then, by ill-chance, the windlass on the motorsailer would not function. However, after some time the crew managed to get some tension on the anchor chain and relieve the pressure.

Meanwhile, the crews of six or seven yachts on our side of the marina were contemplating leaving our berths and motoring out into the gale if the structure broke up. Not a good prospect!

Pontoon patch-up

Eventually, a local shipwright arrived with some rope, large planks of wood and various floats. He and a mate began to fashion outrigger-type floats to the capsized decking using ropes, long brass screws, beams and plastic barrels as well as large polystyrene slabs. Slowly the pontoon was righted and by mid-afternoon it was possible to safely walk on it.

The gale was abating and a dangerous situation with possible loss, damage and injury was averted. At one stage of this drama, I phoned my wife Linda who was at home in Dublin. She asked me what actions the coastguard was taking?

As this situation developed and looked as if vessels, and possibly lives might be in danger, no one had thought of contacting the coastguard. I asked the skipper of the large boat to phone them. He seemed surprised, but made the call; about half an hour later six people in blue overalls and helmets arrived to assess the scene.

Scoundrel with Ardglass Marina entrance

By this time the outrigger pair were hard at work and it did seem that we might not have to steam out into the ferocious sea visible beyond the breakwater. The Tuesday evening was peaceful as the gale subsided and we slept very well knowing that to make the most of the tide, we would not be leaving Ardglass for Bangor until after 0900.

The passage from Ardglass to Bangor Marina on 29 June saw us depart Ardglass Marina at 0925 with a southerly Force 3-4 and the remnants of a swell from yesterday’s gale. This was a lovely passage in good weather, past the entrance to Strangford Lough and along the east coast of the Ards Peninsula.

Trip hazard

Our approach to the entrance of Belfast Lough was through the Copeland Sound for which we had a fair tide with the Governor port hand buoy and Deputy to starboard indicating the deep channel.

Then, leaving the north cardinal mark off South Briggs Rocks to port we were soon opposite Bangor which is tucked into a bay on Belfast Lough’s southern shore. This superbly-run marina was a comfortable place to spend our third night.

During this passage, I had a painful accident. A loose tangle of lines, mostly the main halyard lay on the saloon sole, just beneath the companionway steps – as throwing the free ends of lines down the hatch is a bad habit that I had picked up during time crewing on racing cruisers.

As I briskly hopped down the companionway steps to make a cup of tea, I slipped on these ropes, fell heavily and my right knee suffered a very forced flexion with some rotation.

The pain was excruciating and I immediately thought I’d torn a ligament at the very least. However, despite being very painful, I was able to gingerly stand and walk; bones and ligaments seemed intact.

Over the next few days, the knee did swell with a considerable effusion but we were able to continue our cruise. Ibuprofen was helpful and though walking distance on shore was reduced and accomplished with a limp, my ability to cycle my folding bike was not impaired.

John Latham with co-owner John McQuaid

Post-storm calm

Scoundrel was more of a nervous witness than protagonist in the storm drama, though she might have been a casualty if things had turned out differently.

The rest of our cruise was free of catastrophe and we had a fair passage from Bangor to Rathlin Island off the Antrim Coast (which boasts three lighthouses), spending a day exploring by bike. From there we took a short sail to Glenarm (with its very welcoming marina) and from thence to Portaferry Marina in Strangford Lough.

After a day visiting the Quoile River and yacht club, in the Lough, we then raced out of Strangford on the ebb and in very light wind motored the 33 miles to Peel on the Isle of Man. Following a day enjoying a visit to Castletown, by bus, we left Peel as the flap gate opened at 1600 on 7 July and we experienced a lovely clear night sail back to Dun Laoghaire.

John Latham in Peel

As our first cruise post pandemic, this could have been described as a ‘shakedown’. Despite the unexpected occurrences, it was an enjoyable return to coastal passage-making and exploration.

We never reached our original goal, Tory Island off the North West Coast as during late June and early July that area experienced very high winds. We can highly recommend Rathlin, Strangford Lough, and of course the Isle of Man, as excellent cruising destinations.

Lessons learned

- You can never do enough man overboard drills.

- Throwing lines are useless if not secured to the boat!

- Whether berthed on a marina or at anchor or on a mooring, your boat is still afloat and you should expect the unexpected.

- Call the coastguard early when boats or lives are at risk.

- Make sure that the companionway and the sole beneath it have no trip hazards.

Send your boating experience story to pbo@futurenet.com and if it’s published you’ll receive the original Dick Everitt-signed watercolour which is printed with the article.

Why not subscribe today?

This feature appeared in the September 2023 edition of Practical Boat Owner. For more articles like this, including DIY, money-saving advice, great boat projects, expert tips and ways to improve your boat’s performance, take out a magazine subscription to Britain’s best-selling boating magazine.

Subscribe, or make a gift for someone else, and you’ll always save at least 30% compared to newsstand prices.

See the latest PBO subscription deals on magazinesdirect.com