A knockdown wave inflated the crew's lifejackets and broke the skipper's leg as they tried to rescue a man overboard in 3-4m waves and 45mph gusts close to shore

For more than 40 years I have been taking part in the Round the Island Race on and off, writes Steve Daniel.

This year, with a scratch crew, we decided to give it another bash in my boat Walkabout IV, a Dufour 40.

The crew was myself, my brother Nigel who I’ve sailed with for over 60 years, a close friend’s son Tom Brown, my friend Keith Fisher – a fellow volunteer from Testwood Lakes Sailability – and James Robinson Ranger a friend from Royal Southampton Yacht Club (RSYC).

We hadn’t sailed together collectively before but all at various times had with me. Three old farts and two youngsters.

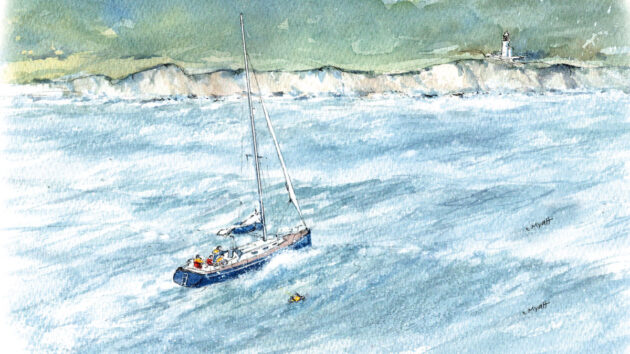

View from St Catherine’s Point Lighthouse, at Niton. Credit: Caitlin D’Arcy

The forecast was lively but not extreme, so after an early departure from the RSYC pontoon we were away down the Beaulieu River making tea and bacon butties.

After a cracking start under full sail, we left Cowes, Isle of Wight, heading for The Needles Lighthouse, progressively reefing as we went.

James and Tom, the fit young men, were on the foresail tailing and winching. James rarely uses the low gear and has to be reminded when to stop!

Leading our class on corrected time at the Needles we made the decision to carry on, despite the worsening weather conditions, reasoning that it was downhill to St Catherine’s Lighthouse at Niton and Bembridge Ledge then in the lee of the island back to Cowes.

Nigel and I had sailed in worse.

Knockdown

We were seeing 25 to 30 knots of wind on a middling reach with time for coffee and biscuits. The sea state was 2-3m waves.

Approaching St Catherine’s, Nigel passed the helm back to me. We were trying to edge out to sea to miss the worst of the overfalls but having to go with the breaking waves as and when to avoid being caught broadside.

All was going to plan until we went down a breaking wave which we now believe had a step in its face which flooded the cockpit, and we rounded up.

Most of our lifejackets automatically inflated under the deluge. Nigel was tethered to windward and held on to the lifeline and was the only one whose lifejacket being manual hadn’t inflated.

The route of the Dufour 40, Walkabout IV. Credit: M Nelson

As we surfaced a rapid head count revealed three out of five crew plus a pair of legs over the top leeward guard wire but still hooked on, Tom and Nigel soon had James back aboard, which was no mean feat as he’s a large lad at 6ft 6in.

Tom had quickly identified Keith in the waves 15m to leeward with lifejacket inflated and two thumbs up. Keith was okay in the water so it wasn’t a big issue.

It was just a question of going through our man overboard (MOB) drill, however we only had about 300m of usable sea room back to St Catherine’s Point.

Having inflated lifejackets felt like trying to do a MOB recovery in a neck brace – they were just in the way.

Mine’s a decent Spinlock and I had the hood flapping around, the light on its stalk and everything else.

It’s wonderful when you’re in the water, I bet, but in that situation, I was in two minds about sticking a knife through it.

Recovery action

We quickly had the jib furled and engine running after a loose rope overboard check, being within 300m of a lee shore, time was of the essence.

One failed rescue attempt down, Nigel, a retired Master Mariner, put out a Pan Pan on the handheld VHF radio advising the Coastguard that we had a potential situation.

We’d had problems with the sail slides breaking so we didn’t really want to take the main down if we didn’t have to.

View from St Catherine’s Point Lighthouse, at Niton. Credit: Caitlin D’Arcy

But after two attempts we concluded that the falls of the loose mainsheet were a liability hooking up over the sheet winches and we were limited in our manoeuvring by having to avoid gybes, so dropped it.

Nigel had looked at the bespoke rescue throwing device but concluded: “That’s useless in this wind.”

The line was too light to get to our MOB.

Instead, he selected a 12m x 12mm mooring warp which was heavy enough to throw in the wind, and easier to grasp.

You look at all these nice little gadgets you’ve got on board, but when the chips are down it’s “No, let’s go back to basics and throw a warp.”

It’s much easier to get across, the guy can hang on to it, and I can tie the end of it to the boat.

On the third attempt, we passed Keith about 3m off to our port heading directly into the wind and successfully got the line to him from the shrouds.

Tom and James were then able to bring Keith toward the stern, around to the bathing platform and the lowered ladder.

Tom and James transferred to the bathing platform remaining hooked on.

Retrieval success

They grasped Keith and managed to turn him, so he sat on the bathing platform and then hooked his tether to the boat.

He’d been unclipped in the first place because he was moving in the cockpit.

From a manoeuvring viewpoint, I was very aware of not running Keith over and the vicinity of the propeller to him, maintaining enough way to keep the boat head to wind and seas, and not wrenching the throwing line from his hands.

Nigel had tied the warp off to the boat but kept it slack in his hands, so the load didn’t snatch the warp out of Keith’s hands.

Once Keith was safely in the cockpit, we could assess his condition, which was good and then got him below and dry.

Steve says: “It’s not often that a sailing photo looks worse than you remember!” Credit: Caitlin D’Archy

During the rescue, Tom had spotted a drone keeping station above Keith.

This was really helpful and good thinking on the part of the drone pilot [event photographer Richard Langdon] to give us another reference point.

We radioed the Coastguard to inform them of a successful rescue and thanked them.

The Bembridge Lifeboat was by now also standing by us and in radio contact.

We were able to reassure them that Keith was well, and did not need transferring to the lifeboat.

He was coherent, had no physical injuries and was in good spirits, with little or no water inhalation; we got him into dry clothes and a sleeping bag.

After a big thank you to the RNLI crew, we wished them well for the rest of the day, then I sent a text to the Island Sailing Club to inform MOB recovered and phoned my wife Tina, our shore contact, so hopefully, all loops were closed.

We continued on toward Bembridge Ledge under reefed jib, then up into the lee and relative calm of Bembridge for a sort out and pack away before motoring back to Beaulieu.

Without that bathing platform the recovery would have been more difficul. Credit: Caitlin D’Arcy

We believe that Keith had been in the water somewhere between 10 and 15 minutes. He was soon up and about making a coffee for us all.

And another thing… During the knockdown, I managed to break my leg.

As we got wiped out in that wave, I was sat in the cockpit steering and I slid from the windward side and finally pitched up right on the pushpit on the leeward side.

Somewhere in that motion, my leg must have got trapped. It wasn’t until after we’d got Keith down below that I realised how bad it was.

It was badly swollen and I couldn’t put weight on it.

At casualty the following day, I was told it was a fractured tibia.

Once we were upright with Keith back on board, we were fine.

If the mainsail had still been intact, we’d have completed the race.

In hindsight should we have turned back at the Needles? The whole crew agreed that we should have gone on.

The conditions were challenging but it’s always a skipper’s responsibility whether to go or not.

Steve Daniel on the helm of Walkabout IV and Tom Brown in front- trying to sail in inflated life jackets on the way back. Steve Daniel is a retired ship designer who learned to sail from age six, living in a Devon fishing town. He now lives in the New Forest. Of 939 entries in the Round the Island Race on 15 June, 418 retired and 154 completed the 50-mile course round the Isle of Wight. Among those to retire was Steve’s Dufour 40 crew, after a man overboard recovery in testing conditions

Round the Island is a great event. We don’t take it too seriously.

St Catherine’s Point has always been a bit of a nemesis of mine.

Over the years I’ve sailed the race in all types of boats and one year in an Ultra 30, we were capsized off St Catherine’s for an hour or so; I was on a Firebird catamaran two-handed one year and collapsed the mast at 23 knots, three miles off St. Catherine’s.

I suppose I’ve got the T-shirt now!

These days it’s usually a much quieter affair. We just go out to enjoy ourselves as a bunch of mates. It’s a huge relief that all ended well.

Success really came down to the excellent performance of the crew and Walkabout: calm, decisive and focused.

Keith didn’t panic, he still dinghy sails at 76 and is used to the odd seawater bath in pursuit of his sport. The rest of us played our parts as a team.

James, in spite of suffering from seasickness, was still able to make a decisive contribution.

Lessons Learned

- Self-inflating lifejackets are great when you fall in but a liability inflated on board. Working in a neck brace comes to mind, but I’d still wear one.

- There is no regularity in waves, they are what they are.

- Think hard about what constitutes a good throwing line.

- It is naive to think a man overboard drill with a bucket and fender in a sunny Force 3 really prepares you.

- Having a bathing platform certainly aided the recovery.

- As soon as possible secure (clip-on) the recovered crew – even passing a rope through their harness.

- Thanks to photographer Richard Langdon who flew a drone over the top of Keith in the water – a sensible action to give us a reference point.

- Think about the MOB perspective – Keith said it was really unnerving seeing a relatively large yacht 3m away and 3m above him on a wave, praying that it wasn’t going to be washed sideways onto him.

- Windward versus leeward pickup. Our successful pickup was directly to windward maybe with slight leeward bias. This reduced loads between MOB and boat. Windward bias would have increased those loads with the boat being blown and washed away from the MOB increasing those loads.

- Examine and improve the cockpit hook-on points so there isn’t an over-reliance on the jackstays. This is an obvious primary safety feature that many yacht manufacturers overlook.

- The broken mainsail slides/plastic shackles were a weakness that prevented the main from being properly stowed. A luff partially adrift in wind becomes a matter of tear along dotted line until it is completely out of control.

- It’s much easier to recover an overboard crew member who is clipped than to reconnect with a disconnected crew member.

- Think hard about how you would do an MOB recovery when sailing short-handed.

- I intend to replace the topping lift with 5mm Dyneema 15m over length led back to the coachroof winches. It will have an eye 5m up from the boom end and a lazy line attached to the topping lift via a floating ring. The other end will be attached in the area of the gooseneck so with the topping lift clutch released, the topping lift can be recovered to the inboard end of the boom with the mainsail up or down. The eye in the topping lift can take a safety line etc to haul the MOB aboard, ideally while steaming gently ahead to use the lowest freeboard point to haul aboard.

- Could we have recovered amidships with various devices? Nigel and I believe the roll of the boat, and huge variation of wave height would put the MOB at huge risk of physical injury and the crew on deck at risk of becoming further MOB victims. Recovering over the stern reduces these risks and allows the boat to keep station.

- This was our first MOB in over 60 years of sailing.

Expert response

Richard Falk

Richard Falk, Royal Yachting Association (RYA) director of training and qualifications, comments: Sailing, much less racing, in extreme conditions is always challenging. What may be run-of-the-mill for an experienced crew on a familiar boat can be extremely challenging for a less experienced crew on an unfamiliar boat.

“While this was a scratch crew, both skipper and crew clearly felt that collectively their experience was sufficient to proceed. It goes without saying that all crews should be briefed on and have the opportunity to practice MOB, reefing, and so on. On this occasion, despite the injury to the skipper, both he and the crew remained calm and carried out an effective rescue.

“There is a lot of equipment on the market that is great on a calm, sunny day, but as useful as a chocolate fireguard in heavy conditions such as encountered on this year’s RTI race. The experience on board meant they were able to identify this and to improvise an alternate solution in getting a warp to the MOB, rather than using the purpose-made but ineffective heaving line.

“Dropping the main and alerting the coastguard were also sensible decisions. The crew’s experience with auto-inflate lifejackets is not uncommon. On one hand, they are helpful in the event of a crew being injured or knocked unconscious as they go overboard, but on the other hand, they can be prone to unintended inflation in heavy conditions.

“This can be mitigated by a), being selective in which crew positions are equipped with auto-inflates and b), carrying spare lifejackets and rearming kits.

“You can learn the basics of MOB recovery in all entry-level RYA courses. But it is essential to then practice in varied conditions and in the context of your vessel and crew. Every day is a school day at sea!”

“It was like doing a MOB recovery wearing a neck brace” – says Round the Island Race 2024 man overboard skipper

As if this year’s Round the Island Race wasn’t tough enough for competitors with winds gusting 45mph and a rough…

“Tough conditions” for Round the Island Race sailors and lifeboat crews providing safety cover

"The weather may not have been on our side for parts of the day, but what an incredible experience had…

What I learned during a boat knockdown while sailing alone

Freya Terry gets an early lesson in the perils of single-handed sailing when she embarks on a round-UK and Ireland…

“I had a banana for a mast” 300 miles offshore: Lessons learned from a mid-Atlantic knockdown

Golden Globe Race entrant and former Clipper Race skipper Guy Waites suffers mast failure 300 miles from the Azores

Want to read more seamanship articles like “The boat was knocked down, our lifejackets inflated, and then we saw Keith in the water!”?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter