Configuring the NoLand RS11 Engine Data Converter

The NoLand RS11 has six configurable input channels and two pulse-type channels. It comes with a set-up utility software package and a USB lead to link your computer to the device.

NoLand RS11 CANbus Engine Data converter

The set-up utility allows each channel to be configured to output a particular type of data and to set the calibration of the sender connected to the channel.

Channel allocation

A1 Oil pressure

A2 Coolant temperature

A3 Fuel tank level

A4 Domestic consumption current

A5 Charging current

A6 Battery 2

P1+/- Engine revs

P2+/- Not used

Engine hours are automatically logged, and you can set the existing engine hours into the RS11 (as its starting point) via the set-up utility. The unit is supplied from 12V or 24V, and the 0V is connected to the newly-installed instrumentation 0V bus.

Sender calibration

The oil pressure, coolant temperature and fuel level senders are resistive, and to create a voltage at their terminal they require a small constant current passing through them. If the current remains constant, then (by Ohm’s law) the voltage at the terminal will be proportional to the resistance which, of course, is determined by the oil pressure, coolant temperature or fuel level. The constant current is provided by the RS11 channel itself. (If piggybacked off an existing instrument, that will provide the constant current.)

Sender voltages displayed in the ‘terminal viewer’ window.

How the set-up utility works

An assumption is made in the RS11 that the relationship between the parameter being measured and the voltage seen at the sender is a linear one. To set this up we need to configure low and high end operating points, and the RS11 will ‘draw’ a straight line relationship between them. This works well for the oil pressure and the fuel sender, but is a limitation with the temperature sender. The utility helps by displaying the voltage at the sender connected to each channel in the ‘terminal viewer’ window. The pulse channel (P1+/-) is calibrated by entering a multiplier in the port RPM box.

RS11 set-up utility.

Oil pressure

The new sender has two terminals, the resistive sender which is wired back to input A1 and the loss of pressure alarm switch terminal which has the original wire reconnected.

The set-up utility is now used to configure the channel: firstly we select ‘port’ engine (instance 0, the default for a single engine). It then allows A1 to be set to Oil Pressure and the current source turned ON. The sender voltage at zero pressure can be read from the terminal viewer window, with the engine switched off.

This gives:

Sense volts 1 (the sender voltage) = 0.1V

Field value 1 (the oil pressure) = 0 psi

For the high-pressure value, as this is a new sender, we will have to rely on the manufacturer’s data sheet to calculate this, and the fact that NoLand Engineering quote their constant current as around 9mA. Taking 7 Bar (100psi) at start-up, the manufacturer quotes a sender resistance of 119Ω, resulting in a sender voltage of 1.07V (119 Ω x 0.009A).

This gives the high value:

Sense volts 2 = 1.07

Field value 2 = 100 psi (7 Bar converted as I prefer pressure in psi).

Finally, set the alarm value to 00 to disable as the original alarm is still connected.

Coolant temperature

The graph shows how temperature sender characteristics are non-linear so a choice of operating point has to be made, accepting that away from that point the reading becomes less and less accurate. This actually isn’t a problem, as the only temperature of real interest is the 60°C -70°C normal operating region. If things go wrong and temperature rises, it will show up on the display: accuracy is secondary to the fact that it would be running ‘higher than usual’. Don’t forget, you still have the alarm switch function of the original engine electrics, and an early warning alarm value (say 85°C) can be set in the RS11 so the chart plotter sounds off before then.

Temperature sender’s non-linear characteristics.

Fuel tank level sender

Hold the sender with the float at the bottom and read the voltage in the terminal viewer, and repeat with the float at the top.

Domestic consumption and charging current measurement

Again this is straightforward, as the current signal for both the shunt (domestic consumption) and Hall sensor (charging), amplified by the AD50 differential amplifiers, give an output of 50mV/A and is linear. No current source is required.

Battery 2 voltage

No sender is required, and the set-up is simple.

Engine revs

Connect the ‘W’ terminal on the back of the alternator to the P1(+) input and P1(-) to 0V: this isn’t normally necessary, but without it occasional glitches will occur with some alternators. The calibration is set by entering a multiplier value in the Port RPM box and matching the displayed value with the rev counter. For this engine/alternator combination, the value is 11.

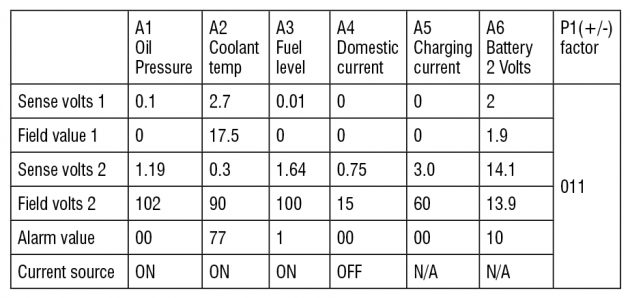

The table below shows the full set-up. A little trial and error is required to get the displayed values just right. Where you have an alternative means of taking the same measurement, a comparison can be made. The main concern, however, is to detect a change in the normal operation of the engine due to a problem: absolute accuracy is a secondary issue, really.